Deflation, negative interest rates and the derivatives mountain

In a press conference last week, Fed Chair Janet Yellen was asked about negative interest rates. Yellen dismissed the possibility, but also said if "we found ourselves with a weak economy that needed additional stimulus, we would look at all of our available tools, and [a negative rate] would be something that we would evaluate in that kind of context."

Just a week later 1-month Treasury bill yields went negative, without the Fed even doing anything.

This may not sound like much, but in monetary policy negative interest rates are the military equivalent of a thermonuclear bomb.

It's extremely important to understand what negatives interest rates are and why this is happening.

What is it?

Negative interest rates are exactly what they sound like. You are paying someone to loan them money.

Since this is typically associated with bonds, it's like paying $100 for a bond that will pay you $98 back after a year.

The Impossible

Let's be clear on something: negative interest rates are not supposed to happen. Period. The entire discussion of NIRP has been the domain of theoretical economics for generations.

The reason is obvious. Why loan money to someone at a negative interest rate when holding cash instead makes more sense?

The St Louis Federal Reserve said this just two years ago.

Conventional wisdom is that interest rates earned on investments are never less than zero because investors could alternatively hold currency.

It's more than conventional wisdom. There is an entire economic theory behind this called Zero Lower Bound.

Paul Krugman wrote, "the zero lower bound isn’t a theory, it’s a fact, and it’s a fact that we’ve been facing for five years now."

Zero Lower Bound is associated with the Keynesian economic problem of a Liquidity Trap.

And yet the impossible has happened in Europe and Japan, and even some negative mortgage rates to go along with deflation in Europe and Japan, and now the Fed is considering it as a policy.

So why not hold cash instead of buying bonds with negative interest rates? Because if you are a multinational bank required to hold tens of billions of dollars in reserves, there simply isn't enough physical cash in the world, nor enough bank vault space to put it in.

That brings us to bank regulations.

After the 2008 financial collapse, bank regulators and politicians, instead of doing their jobs and breaking up the TBTF banks, decided that it would be better to just make the huge banks carry more reserves to support their gambling.

This made the banks more stable, but it also meant that they would have to buy hundreds of billions of dollars of AAA-rated securities. With the collapse of the mortgage-backed securities market, that meant much greater demand for the only large source of AAA bonds - Treasuries.

The rule of thumb in bonds is that the higher the price, the lower the yield.

Why is it?

Consider the final sentence in that 2013 Federal Reserve report.

The existence of negative yields, however, provides no support for the argument that central banks should consider negative policy rates as a monetary policy tool.

Whenever something supposedly impossible happens the first question should be, "why is it happening?" Surprisingly few people are asking that question.

Whenever a Fed report says they shouldn't use something, and just two years later they are considering using it, it should set off some alarm bells.

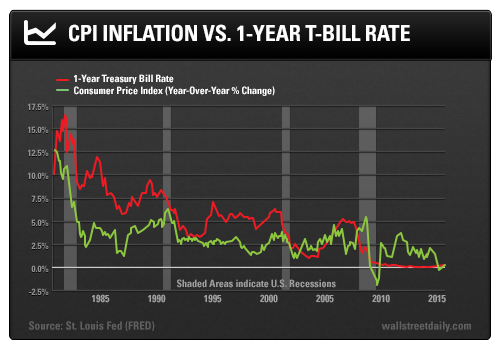

So why is it happening? I think there are several causes for this, including fears of global deflation.

Why deflation? Because artificially low interest rates encouraged massive borrowing without producing massive economic growth.

And so here we are, just 8 years later, with nearly $60 trillion in new debt piled on top of the prior mountain - while GDP grew by only $12 trillion over the same time period.

In other words, instead of saying to ourselves: Hmmm.... it was probably a terrible idea to pile up debt at 2x the rate of income growth, what the world did instead was to double down on that terrible idea and pile on more debt at 5x the rate (!) of nominal GDP growth.

Rapidly increasing debt in a stagnant economy means the economic surplus will get consumed by interest payments, even when interest rates are low. That translates into deflation.

Plus, massive overcapacity in China means rapidly falling prices for consumer goods, which becomes price deflation in America through our huge trade deficit.

Most economists will point to bond supply and demand for this situation, and they are right.

However, they fail to point out that both the supply and demand are entirely artificial.

Let's start with the Liquidity Trap that Krugman has warned about.

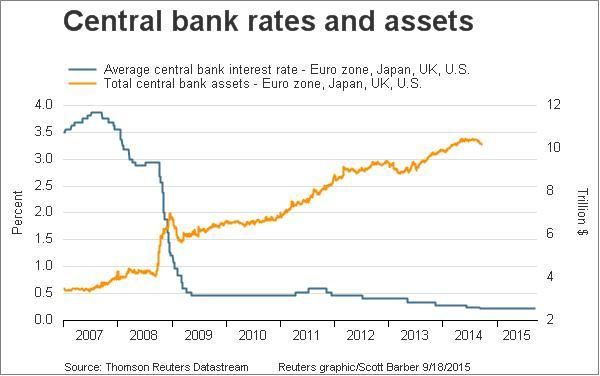

Delaying its first rate hike in nearly a decade after taking a pass in June and July means the U.S. central bank may have stepped further away from an escape from zero rates and $3.7 trillion of asset purchases bloating its balance sheet.

No central bank in post-War history has ever successfully made this escape. All four of the developed world’s biggest central banks — the Fed, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England — are in different stages of the same situation: near-zero rates and holding huge piles of financial assets.

The danger mentioned here is that Yellen won't be able to raise rates before the end of this business cycle, i.e. the next recession. This would mean that the Fed would be without any "ammo" to fight the recession, with the exception of extreme and unproven monetary policy.

But there is something else from the chart above that needs to be noted - the enormous pile of assets (mostly bonds) that the leading central banks have built up, and how that has pushed rates down to zero while pushing those financial asset prices up to nosebleed levels.

You simply can't create $10 Trillion dollars to buy financial assets and not create price distortions. For example, The Federal Reserve purchased 71% of all Treasuries for sale in 2013, and the Fed has no intention of trying to sell these assets anytime soon.

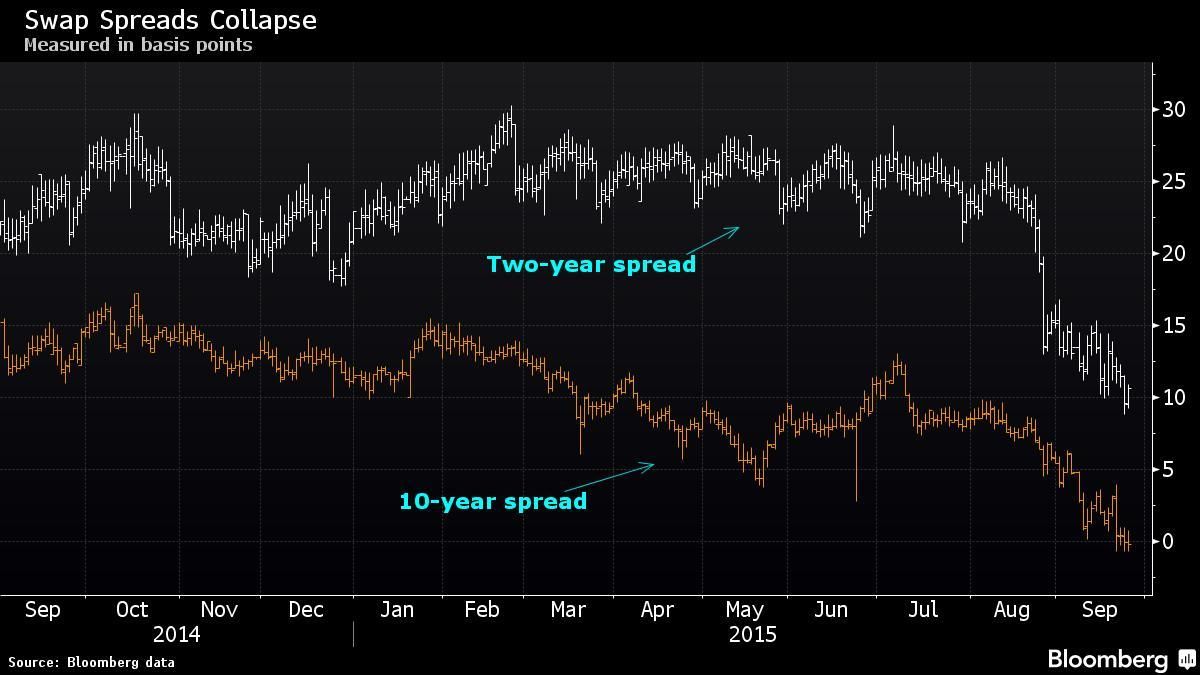

Such enormous demand for these bonds has created periodic liquidity problems, which translates into volatile price swings. For months now traders have been increasingly concerned with bond market liquidity.

they aren’t big buyers and sellers of corporate bonds anymore. This has made it harder for investors to trade large blocks of bonds-and it’s making them worried that they may have to take big losses if they need to sell assets in a hurry.

It's important to remember that the world has never seen this before. It's completely unprecedented to have such activist central banks, and their policies have no historical comparison.

Simply put, this is experimental monetary policy.

What's more, the monetary policy of QE has a poor record, both for failing to stimulate the economy, and for increasing wealth inequality.

There is also another thing to consider, derivatives.

At the height of the financial crisis, the unprecedented decline in swap rates below Treasury yields was seen as an anomaly. The phenomenon is now widespread.

Swap rates are what companies, investors and traders pay to exchange fixed interest payments for floating ones. That rate falling below Treasury yields -- the spread between the two being negative -- is illogical in the eyes of most market observers, because it theoretically signals that traders view the credit of banks as superior to that of the U.S. government.

Insiders have called it “perverted”.

Swaps in this case aren't credit default swaps, but are instead interest rate swaps.

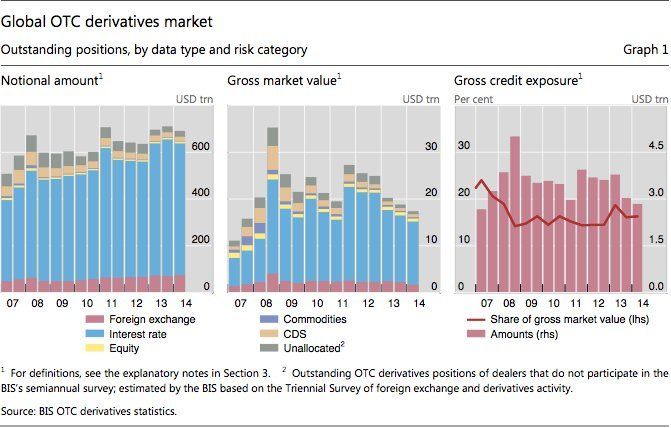

What most people don't realize is that the interest rate swap market is far larger than the credit default swap market that scared so many people in 2008.

the global notional market for interest rate swaps was about $560 Trillion last year.

While using notional values dramatically overstates the actual amount of money at risk (unless there are systemic defaults), even a small fraction of that mountain of money dwarfs of the GDP's of the world.

What this means is that if interest rates were to rise, and rise quickly, it would trigger these interest rate swap contracts (i.e. someone would have to pay).

When interest rates rise, they rise across the board for an entire nation, and they may indeed help trigger interest-rate increases in other nations as well. Issuers have entered into trillions of dollars of contracts with Wall Street and other financial firms to cover their risk if interest rates increase. And if interest rates do increase substantially – they increase for the nation as a whole, in every state, for every borrower, and for every category.

So there is close to 100% correlation – the simultaneous losses being incurred could be likened to one firestorm spreading over the entire country.

And the reserves that were established to cover statistical assumptions of uncorrelated losses quickly disappear when it is correlated losses on a national basis that happen instead.

Wall Street and the banking industry remain as highly over-leveraged as ever. Just where are these hidden reserves of many trillions of dollars worth of capital to honor all of the derivatives contracts?

...

Do Wall Street and the other providers of interest-rate derivatives actually have the capital tucked away somewhere to cover the many trillions of dollars in increased interest payments for the entire nation (and the entire world), year after year, if rates were to rise by 5% or 10% or even more?

In practice, we know that Wall Street wasn't good for their promises on a little more than $1 trillion in subprime mortgage derivatives. There are more than 400 times as many interest-rate derivatives currently outstanding as there were subprime mortgage derivatives in 2008. There's no possible way. It would be an annihilation scenario, short of even greater levels of government interventions.

Since 1981 the bond market has been in a secular bull market. There is almost no one on Wall Street old enough to remember a bond market that didn't go up almost every year.

No one on Wall Street would even know how to trade a secular bear market in bonds.

But now interest rates are scraping rock bottom. They have to go up, short of dangerous monetary experimentation or disastrous global deflation.

That means that probably sooner rather than later, interest rates will go up, and if they go up quickly (like, for instance, because of widespread defaults) then that mountain of derivative contracts will be triggered. A mountain that simply can't be paid.

After carefully watching the financial markets for the last two decades, I've learned a few things about bubbles. I've learned that the best way to spot a bubble is when it no longer makes any sense at all.

When people started talking about the 'New Economy' during the Dot-Com Bubble, because making profits no longer mattered, then tech stocks no longer made sense.

When people with bad credit were going to get rich by flipping houses to other people with no credit during the housing bubble, then real estate no longer made sense.

Now central banks are going to stimulate the economy with negative interest rates, then banking no longer makes sense.

And that's a huge problem, because central banks = currency, and that is a bubble none of us can afford.

I want to be clear that I don't know where this road goes. No one does.

Monetary policy is in uncharted territory, so there are no historical examples to draw from.

There has never been a case of global central bank experimentation like this.

There has never been global debt like this before.

And more than anything, there has never been nominal negative interest rates before. Even during the deflation of the Great Depression interest rates weren't negative.

Never before have all the major central banks ran short of ammo while deflation is popping up everywhere in the globe.

The only thing I am absolutely certain of is that we're rapidly running out of road, and the fact that our global financial leaders and politicians have nearly nothing to say on this matter tells me that they have no ideas.

Comments

I've been working on this essay for a while

I'm not sure if some of the concepts will be clear to non-econogeeks. So give me some feedback and let me know.

heh, I can't rec it anymore over the gos, but I tweet it ...

without even reading it... it's too much for me, but I trust you, so that's all I can give as feedback. I think something in my mind just refuses to be overwhelmed by data driven activism. I am attention-span challenged and a victim of distractions online. That makes me a loser when it comes to read through too many statistical data. I am sorry for that. (Considering that I studied quite a bit of statistics 30 years ago, that's a shame...)

https://www.euronews.com/live

This is an excellent essay.

I appreciate the time you have put into explaining our oh-so-precarious economy to those of us who are not specialists in markets and their normal and abnormal developments.

My one suggestion is that you expand and clarify your summation for a lay audience. Just what does a "currency collapse" mean?

I think a quick reference to and explanation of the hyperinflation of the Weimar Repubic should be frightening enough (albeit quite inadequate inasmuch as the German mark was not, as the US dollar currently is, the world's reserve currency). Briefly, at the start of WW1 in 1914, the exchange rate for the German mark was 4.2 marks to 1 US dollar. Unlike France and Britain, both of which raised taxes to help pay for their war efforts, Germany borrowed to pay for its - and lost the war. By the time the German economy finally collapsed in 1923, the exchange rate for the German mark was 4.2 trillion marks to 1 US dollar. The oft-told tale of Germans needing a wheelbarrow of money to buy a loaf of bread is not hyperbole.

I'm not an economist to know whether or not a banking collapse is the same as an economic collapse. I have read enough history and economics, however, to understand that by whatever name the situation we are in is catastrophic.

This is all beyond terrible news, for the US especially as well as most of the so-called West. As hecate might put it, eleventy quadrllion plus ungood. If we can do nothing else, we can bear witness to the times we live in, staring straight at the freight train bearing down on us ... until we must look away.

Thanks again for this essay, gjohnsit, reminding me to turn my gaze back to the freight train of imminent economic collapse and to bear witness.

Only connect. - E.M. Forster

Thanks for your reply

But I can't really help with the summation because, as I said, this is all uncharted territory.

There has never been a case of global central bank experimentation like this.

There has never been global debt like this before.

And more than anything, there has never been nominal negative interest rates before. Even during the deflation of the Great Depression interest rates weren't negative.

Generally with excessive debt, it means deflation. Currency crisis generally means inflation.

How this plays out is anyone's guess, but the trend can't keep going.