The Other Historical Event We Should Celebrate in July

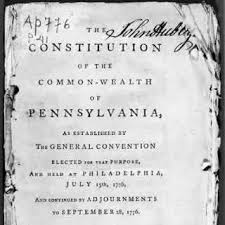

John Adams must have shaken his head as he watched delegates to the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention filing into the West Room of the Statehouse on July 15, 1776. Across the hall in the East Room, Adams and his colleagues in the Continental Congress had recently voted to declare the thirteen colonies independence from Great Britain. Now the newly independent states would each have to create new "republican" constitutions. A month before, Adams had worried that the new constitutions would be influenced by a "spirit of leveling, as well as that of innovation." In the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, perhaps the most radically democratic in the world at the time, Adams worst fears would be realized.

As Gary B. Nash points out in his eye-opening book, The Unknown American Revolution, Pennsylvanians made a sharp break from nearly a century of political tradition in both England and the colonies by opening up the vote to all taxpaying men, rather than just substantial property-owners. All "Associators" or men who had joined the state militia would be permitted to vote if they were 21, residents of Pennsylvania for at least one year and had paid even the smallest tax. But there was one important qualification: it applied only to those ready to swear allegiance to the independence movement. Deprived of the vote were those unwilling to vow that they would not "by any means, directly or indirectly, oppose the establishment of a free government in this province by the convention now to be chosen, nor the measures adopted by the congress against the tyranny attempted to be established in these colonies by the court of Great Britain." By disenfranchising Tories and "Moderates," those still opposed to outright independence, Pennsylvania's new electorate would not be representative of the people as a whole but rather of those committed to independence and political change.

As Nash recounts, twelve days before the election to choose constitutional convention delegates, a Philadelphia mathematics teacher named James Cannon, who had risen from poverty but still felt a bond with the lowest ranks, addressed a broadside to the "Several Battalions of Militia Associators in the Province of Pennsylvania." He reminded the men who were shouldering arms and preparing for battle with the British that the "judiciousness of the choice which you make" will affect "the happiness of millions unborn." Cannon urged the soldiers to reject the upper-class view that delegates needed "great learning, knowledge in our history, law, mathematics etc., and a perfect acquaintance with the laws, manners, trade, constitution and policy of all nations." Such men were exactly those to be distrusted if the great work to be accomplished would serve "the common interests of mankind."

What should be preferred to deep learning and professional status? "Honesty, common sense and a plain understanding, when unbiased by sinister motives," counseled Cannon. For him those qualities were "fully equal to the task." Men like the voters themselves were most likely to frame a good constitution. "We are contending for the liberty which God had made our birthright," Cannon told the militiamen, "All men are entitled to it and no set of men have a right to anything higher."

The eventual delegates numbered ninety-six. Most were farmers, a few were merchants and lawyers, others were artisans, shopkeepers and schoolteachers. As Nash relates, it was not uncommon for "an ironmonger born in Upper Silesia to be flanked by an Ulster-born farmer and an Alsatian-born shopkeeper as the deliberations went forward." A majority were immigrants or the sons of immigrants from Ireland, Scotland and Germany and many were only in their mid-twenties. All but eight were from rural counties outside Philadelphia. About half were militiamen with most having been elected officers by the rank and file.

Ben Franklin himself served as the convention's president, though he was asleep most of the time and sometimes stepped across the hall to sit in at sessions of the Continental Congress. Another notable Pennsylvanian, Tom Paine, was absent but his ideas were very much on the minds of many of the delegates.

Working for eight weeks the delegates considered and then rejected three of the most time-honored elements of English political thought. First, they scrapped the idea of a two-house legislature, which they saw as a replica of British system with its House of Lords, representing the aristocracy, the wealthy and big landowners and House of Commons representing everyone else, at least in theory. The case for unicameralism rested on the long historical experience of upper houses generally reflecting the interests of the wealthy in the colonies. The framers also drew on the idea of the town meeting, the fact that the Continental Congress itself was unicameral and that Pennsylvania had experienced almost a century of one-house rule with no ill-effects. Largely through to efforts of progressive, New Deal Republican, Senator George Norris, Nebraska did away with its upper state house in 1937 and remains the only state in the union today with a unicameral legislature.

Second, the drafters abandoned the idea of an independent executive branch with extensive power, particularly to veto legislative bills – a governor's power commonly found in the British colonial governments and which Queen Elizabeth II still technically retains in to this day. Instead, the convention provided for an elected plural executive branch, composed of a president and council. It was empowered to appoint important officers, such as the attorney-general and judges but was given no legislative veto power. Its duty was to implement the laws passed by the legislature, not to amend or veto them.

Finally, the drafters reaffirmed the extension of the vote to the widest possible number of free, white males, the most liberal franchise anywhere in the world at the time. Only apprentices and the deeply impoverished, excused from paying any tax, were excluded. Nash observed: "This was a flat-out rejection of the idea that only a man with "a stake in society" would use the vote judiciously. After all, was not risking one's life on the battlefield evidence of a stake in society?"

Other provisions of the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776 were designed to prevent concentrated political power. Annual elections, also used in the colonial period were retained. In addition, the constitution guaranteed that the doors of the legislature remain open to "all persons who behave decently," so the people could monitor their elected officials. All legislative debates and votes were to be printed weekly in English and German, for all to see. All laws passed were to be printed and distributed for "consideration of the people." This allowed for time for public discussion of each law before the next annual election of representatives. The next legislature would then vote on the law passed by its predecessor. Vermont was the only state to follow Pennsylvania on this.

Three final provisions "nailed down," in the words of Nash, "the radical democracy desired by the Pennsylvania delegates." First, they restricted legislators to serving no more than four one-year terms every seven years. Second, they created a "Council of Censors" to be popularly elected every seven years to review the constitution (Vermont again followed Pennsylvania in this regard) and, finally, mandated the reapportionment of the legislature every seven years on the basis of census returns. This commitment to proportional representation was followed by only four states and was not achieved by the U.S. House of Representatives until 1962, when the Supreme Court ordered it as a result of the "one man-one vote" principle laid down in the Baker v. Carr case.

Unfortunately, this unique experiment in American democracy was not destined to last too long. In 1790, after years of attacking it, conservatives finally succeeded in overthrowing the radical Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776. Gaining the upper hand in the legislature, they called for a new constitutional convention, brought in all of the governmental structures rejected by the 1776 delegates and considerably scaled back white male suffrage. It was a constitution unworthy of America, Tom Paine believed. One might also note that it strongly resembled the new federal Constitution, ratified only two years before, the one we are still living under today.

Comments

Very informative.

Thank you.

I question why this country celebrates the fourth though. This is a good year to study what the majority think about it.

As it falls on a Wednesday, the muckity celebrate it on the 30th of June so as not to have to work the next day.

The celebrations may continue until the first of the hallmark holiday month and then tic up slightly for the actual day we are disposed to recognize.

I find nothing celebratory about a day that means nothing to the masses. I would like to know how many really feel independent.

Sorry to rant.

Peace.

Out.

Regardless of the path in life I chose, I realize it's always forward, never straight.

It's an important day

to remember if for

no other reason than a bunch of wealthy guys put their name on a piece of paper for the whole world to see, double dog daring the world's baddest military to come kick their ass, knowing full well that if their effort failed they all would be hanged by the neck until dead. Every last one of them. Their only "reward" being they'd likely get their money back if successful. And their freedom from Britain, of course. No other revolution comes to mind where the rebel rousers signed their names declaring their intent - and posting it everywhere.

As for black and brown people... I grant that there's damn little to celebrate, and have often wondered why they stand for a "national anthem" that does not include them, ignores them, would rather they weren't seen or heard. And then get chastised for "taking a knee." The 4th wasn't about them or their freedom. Still, though, it's a Joe Biden bfd. Break out the Bud and the fireworks! And not surprised to see

allmostly white people at the events. But to disregard the 4th is to disregard the events from 1760 (if not before) to 1781 (and beyond) that signify the birth of this "experiment." One that now at least, at least on paper, includes black and brown people.the little things you can do are more valuable than the giant things you can't! - @thanatokephaloides. On Twitter @wink1radio. (-2.1) All about building progressive media.