Gennifer Flowers will remind Trump of something he is - an adulterer. Mark Cuban will remind hm of something he's not - a billionaire.

Anti-Capitalist Meetup: so many Conspiracy-Theory Machine (CTM) factories for disinformation

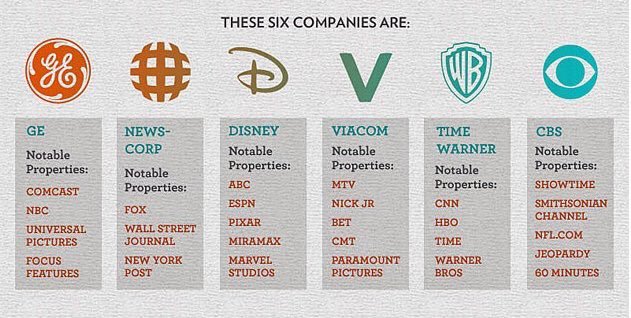

this image was created before Comcast acquired NBC/Universal

Disinformation operates everywhere with the continuing tendency to alienate the electorate as well as its historical consciousness of race and class. It seeps into discourse in a variety of venues and are a function of how social networks are integral to contemporary political discourse. It represents the inequality of power and wealth to proliferate mistruths and misdeeds in the public sphere. It represents the ability of capitalism to shape a message that allows the self-dealing and self-serving to maintain normalized, legitimated dominance over the dispossessed.

One’s impulse is to question the hegemonic power of those who own the networks that enable disinformation, but for many that is a step too far. “Rather, the question instead becomes that of how links between nodes are formed, what those links are, where the hubs are, and how it might become possible to form new networks.” That may be the best first step, to see how disinformation disrupts the mass media landscape and its communication networks and corrupts democratic processes.

An example of disruption of such new communication networks is disinformation at small and large scale levels. Disinformation is often referred to when producing conspiracy theories of the most absurdly debunkable variety — for example UFOs, birthers, truthers etc… OTOH, disinformation is also the weapon for state-sponsored psychological warfare operations (psyop), industrial greenwashing, and complex international negotiations. Needless to say, their megaphonic amplification comes through mass media monopolies/oligopolies that are an important use of political and cultural capital.

“The disinformation (dezinformatsiya) campaigns are only one "active measure" tool used by Russian intelligence to "sow discord among," and within, allies perceived hostile to Russia.”

The Kremlin’s clandestine methods have surfaced in the United States, too, American officials say, identifying Russian intelligence as the likely source of leaked Democratic National Committee emails that embarrassed Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.

The Kremlin uses both conventional media — Sputnik, a news agency, and RT, a television outlet — and covert channels, as in Sweden, that are almost always untraceable.

A simple small scale example will occur at Monday’s POTUS debate. The first ring of the 3-ring debate circus will feature some spectacular yet luridly minor disinformation sideshows involving micro-aggressive acts representing sex and money as they have during the entire US campaign:

Gennifer Flowers, who carried on a 12-year affair with Bill Clinton when he was attorney general and governor of Arkansas, might attend the debate at Hofstra University as Trump’s guest, BuzzFeed reported Saturday. The development grew from a Twitter broadside Trump launched earlier that day.

“If dopey Mark Cuban of failed Benefactor fame wants to sit in the front row, perhaps I will put Gennifer Flowers right alongside of him!” he tweeted.

It was a shot at Clinton’s decision to seat Cuban, a frequent Trump critic, in the front row as her debate guest, and a signal that the Republican nominee might dredge up past Clinton scandals as ammunition...

The spectacle of the buxom blond lounge singer shooting daggers at Hillary Clinton — perhaps just a few seats away from her former lover, Bill Clinton, who is expected to attend — would only draw more eyeballs to a debate already expected to attract 100 million viewers.

In this debate example, the pathological issues from 1992 might be revisited if only to throw off Clinton’s performance, but its real function is to highlight the structural inclusion of a variety of disinformation campaigns ranging from data leaks, hacking, and collusion among foreign powers beyond the actual media institutions’ own ability to reproduce disinformation as they produce information. Social media amplifies the disinformation effects exponentially as the 2016 campaign has demonstrated.

Capitalist information industries are a key element of capital formation not simply because capital requires valuation data to measure wealth production but also to influence the manufacture of consent necessary to ensure stable capital accumulation and its requisite inequality of race/class.

Disinformation functions better as polarization increases and correspondingly trust/reputation erodes...

Trust – or rather, the absence of it – stands suddenly top of journalism’s talking shop. Gallup in the US releases another of its annual polls that shows trust in the mass media “to report the news fully, accurately and fairly” has dropped to its lowest level in polling history – with only 32% saying they have a great deal or fair amount of such confidence.

Those findings are down eight percentage points from last year. Compare and contrast a whopping 72% trust rating on parallel Gallups in 1972, opinions sampled directly after the Watergate heroics: different reputations, different times.

An essential disinformation as origin story comes with an quintessential entrepreneurial capitalist game, much like the false image presented by political candidates that they are either good stewards of a neoliberal capitalism or maverick venture capitalists whose success will flow like the metered water to the dispossessed in Mad Max Fury Road.

As those of you who have seen the excellent documentary Pay 2 Play know, there is a lot of misinformation surrounding the board game Monopoly. Now Mary Pilon is about to publish a tell-all book, The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game, and the New York Times piles on with an article by Pilon titled “Monopoly’s Inventor: The Progressive Who Didn’t Pass ‘Go’”:

The trouble is, that origin story isn’t exactly true.

It turns out that Monopoly’s origins begin not with Darrow 80 years ago, but decades before with a bold, progressive woman named Elizabeth Magie, who until recently has largely been lost to history, and in some cases deliberately written out of it.

Magie lived a highly unusual life. Unlike most women of her era, she supported herself and didn’t marry until the advanced age of 44. In addition to working as a stenographer and a secretary, she wrote poetry and short stories and did comedic routines onstage. She also spent her leisure time creating a board game that was an expression of her strongly held political beliefs.

Magie filed a legal claim for her Landlord’s Game in 1903, more than three decades before Parker Brothers began manufacturing Monopoly. She actually designed the game as a protest against the big monopolists of her time — people like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller.

She created two sets of rules for her game: an anti-monopolist set in which all were rewarded when wealth was created, and a monopolist set in which the goal was to create monopolies and crush opponents. Her dualistic approach was a teaching tool meant to demonstrate that the first set of rules was morally superior.

And yet it was the monopolist version of the game that caught on, with Darrow claiming a version of it as his own and selling it to Parker Brothers. While Darrow made millions and struck an agreement that ensured he would receive royalties, Magie’s income for her creation was reported to be a mere $500…

More interesting is the story of another anti-monopoly game by an economist, Ralph Anspach

More problematic are the continuing large scale disinformation campaigns that involve not only political campaigns

In his research from St. Petersburg, Chen discovered that Russian internet trolls — paid by the Kremlin to spread false information on the internet — have been behind a number of "highly coordinated campaigns" to deceive the American public.

It's a brand of information warfare, known as "dezinformatsiya," that has been used by the Russians since at least the Cold War. The disinformation campaigns are only one "active measure" tool used by Russian intelligence to "sow discord among," and within, allies perceived hostile to Russia.

"An active measure is a time-honored KGB tactic for waging informational and psychological warfare," Michael Weiss, a senior editor at The Daily Beast and editor-in-chief of The Interpreter — an online magazine that translates and analyzes political, social, and economic events inside the Russian Federation — wrote on Tuesday.

He continued (emphasis added):

"It is designed, as retired KGB General Oleg Kalugin once defined it, 'to drive wedges in the Western community alliances of all sorts, particularly NATO, to sow discord among allies, to weaken the United States in the eyes of the people in Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America, and thus to prepare ground in case the war really occurs.' The most common subcategory of active measures is dezinformatsiya, or disinformation: feverish, if believable lies cooked up by Moscow Centre and planted in friendly media outlets to make democratic nations look sinister."

From his interviews with former trolls employed by Russia, Chen gathered that the point of their jobs "was to weave propaganda seamlessly into what appeared to be the nonpolitical musings of an everyday person."

"Russia's information war might be thought of as the biggest trolling operation in history," Chen wrote. "And its target is nothing less than the utility of the Internet as a democratic space."

“There has never been a document of culture which is not simultaneously one of barbarism.” Walter Benjamin

The literal and figurative (dis)information factory has literal and figurative labor and in the information industry context is the critical intersection of labor and capital where epihenomenal capital as virtual is yet still material as the product of knowledge production and transactional network relations.

...the self-organizing, collective intelligence of cybercultural thought captures the existence of networked immaterial labor, but also neutralizes the operations of capital. Capital, after all, is the unnatural environment within which the collective intelligence materializes.

For the modern CTM factory, cognitive labor or collective, cooperative and noncooperative action are both information labor information capital. Although in the current election CTM factories are really manufacturing conspiracy hypotheses as Trumpians move the US into complex codependency and overdetermination.

The market for memes creates interpretive algorithms that formulate the informational conflicts among the assertions (signs) produced in the dialectical conflict among memes and their reception in social media. For example, contradictory realities about the “factual” degree of domestic and international terrorism are “spun” as interpretive algorithms depending on the ideological position of media channel and their various agents’ trust/reputation. The invocation of Cold War espionage memes overlays the potential for economic espionage and the partisan political disclosure of hacked data during a divisive election campaign.

Capital algorithms are joint labor networks that constitute the organic intersection of labor and capital as message commodities capitalized as hacktivism, media audiences, and subsequent potential voters. Disinformation forms in the resistance to perceived hegemony making the act of challenging disinformation beyond so-called fact checking when critically engaging the conflicts of the ideal and the material revealed by ruthless criticism.

More technically, one can conceive of disinformation as in a (Badiou) extensional network constructing messages is constitutively constructing nodes, links among nodes, hubs, and their networks of information which transmit disinformation (the networks’ disruptor).

These technical terms identify specific agents for disinformation that reveal not only international actors but domestic sources that more often than not are neither critical nor candid about their own degree of disinformation. The recent reporting on the Trumpian agent, Carter Page as a “foreign influence” is one such example contextualized by disinformation campaigns in the context of intrusive Russian actions.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-danger-of-russian-disinforma...

counter-disinformation initiative at the Center for European Policy Analysis,

Information Warfare Initiative

Fifteen years ago, the idea that foreign disinformation might be a problem for European countries seemed ludicrous. Free media looked as triumphant as free markets; Western television and newspapers had comfortable funding and big audiences. But the business model that once supported media across the continent, indeed all across the West, no longer works. Much Western journalism is poorly resourced, and the proliferation of information has made it harder for people to judge the accuracy of what they see and read.

At the same time, authoritarian regimes, led by Russia but closely followed by China, have begun investing heavily in the production of alternatives. Because national media is often weak, it has become far easier for channels such as RT (formerly Russia Today) and Sputnik (a Russian “news” agency) to establish credibility in smaller European markets. But even in larger countries, the Russian use of social media as well as a huge range of online vehicles — “news” websites, information portals, trolls — are beginning to have an impact. Chancellor Angela Merkel tasked Germany’s spy agency with investigating the Russian use of propaganda in Germany after a fake story about a girl allegedly raped by a refugee blew up into a major scandal, thanks in part to a concerted Russian online effort.

The messages have little in common with Cold War propaganda. Russia does not seek to promote itself, but rather to undermine the institutions of the West, often using discordant messages. RT pumps out scare stories about migrants, and also portrays the West as racist and xenophobic. Russian-backed websites promote conspiracy theories — 9/11 was an “inside job,” Zika was created by the CIA — while ridiculing the excellent Western investigative journalism that revealed the ties among Russian politics, business, organized crime and intelligence…

Partly because the U.S. media market is so vast, there is still little understanding of how disinformation campaigns work here either. There is certainly no public analytical database of what Russia says, when and where. Nobody — even in the Western intelligence community — compiles transcripts. Nor do we know which elements of the Russian message are effective, who believes them and why. It’s high time we learned, because other countries, notably China, are beginning to use some of the same techniques. Fifteen years ago, the free press seemed unchallengeable; 15 years from now, we may find ourselves, as Ukraine did two years ago, the targets of disinformation campaigns we are unprepared to fight.

http://theconversation.com/war-of-words-how-europe-is-fighting-back-agai...

Tracing individual strands of disinformation is difficult, but in Sweden and elsewhere, experts have detected a characteristic pattern that they tie to Kremlin-generated disinformation campaigns.

“The dynamic is always the same: It originates somewhere in Russia, on Russia state media sites, or different websites or somewhere in that kind of context,” said Anders Lindberg, a Swedish journalist and lawyer.

“Then the fake document becomes the source of a news story distributed on far-left or far-right-wing websites,” he said. “Those who rely on those sites for news link to the story, and it spreads. Nobody can say where they come from, but they end up as key issues in a security policy decision.”

Although the topics may vary, the goal is the same, Mr. Lindberg and others suggested. “What the Russians are doing is building narratives; they are not building facts,” he said. “The underlying narrative is, ‘Don’t trust anyone.’”

The problem comes from how facts are identical with their narratives since the interpretive and explanatory come with every reportable description of actions, objects, or events. What becomes more insidious is the repetition of first impression messages to attempt to reify their meaning which relies often on the use of social media to mobilize / render viral the disinformation meanings.

Carter Page is a former Merrill Lynch investment banker in Moscow who now runs a New York consulting firm, Global Energy Capital, located around the corner from Trump Tower, that specializes in oil and gas deals in Russia and other Central Asian countries. He declined repeated requests to comment for this story.

Trump first mentioned Page’s name when asked to identify his “foreign policy team” during an interview with the Washington Post editorial team last March. Describing him then only as a “PhD,” Trump named Page as among five advisers “that we are dealing with.” But his precise role in the campaign remains unclear; Trump spokeswoman Hope Hicks last month called him an “informal foreign adviser” who “does not speak for Mr. Trump or the campaign.” Asked this week by Yahoo News, Trump campaign spokesman Jason Miller said Page “has no role” and added: “We are not aware of any of his activities, past or present.” Miller did not respond when asked why Trump had previously described Page as one of his advisers.

Capitalist relations with the Soviet Union e.g. Armand Hammer among others, has been more fluid than the image of Lend-Lease aid during WWII and its economic history needs further research. The history of monopoly capitalism as a structural enabler of other forms of state capitalism needs additional work but the features are there.

(StaMoCap) State monopoly capitalism

an environment where the state intervenes in the economy to protect large monopolistic or oligopolistic businesses from competition by smaller firms.[60] The main principle of the ideology is that big business, having achieved a monopoly or cartel position in most markets of importance, fuses with the government apparatus. A kind of financial oligarchy or conglomerate therefore results, whereby government officials aim to provide the social and legal framework within which giant corporations can operate most effectively.

https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/staff/mharrison/reviews/res...

So what does the Conspiracy-Theory Machine (CTM) factory look like… it is constituted by a complex dialectic dichotomy.

...the self-organizing, collective intelligence of cybercultural thought captures the existence of networked immaterial labor, but also neutralizes the operations of capital. Capital, after all, is the unnatural environment within which the collective intelligence materializes.

It has dichotomous constituents:

1. Virtual, Human, Inorganic/organic Capital an ephemeral but not epiphenomenal, electromagnetic message distribution system (often reified as medium=message) with its messages, on-air celebrity talent and digital production studio apparatus,. We ask if its abstract manifestation is the media industry itself or its articulation in a variety of circulation institutions, networks, stations, and the constitutive message audiences perhaps including the UX devices themselves in terms of their operating systems. (see Google-Android, Amazon-Prime, Microsoft-Windows, Apple-iOS)

2. Virtual, Human, Inorganic/organic Capital an ensemble of material reality, physical network infrastructure, and human labor. We ask if its concrete manifestation is like a 3-D printer or is it like the system/mode of production itself. It’s not so much a Rust-Belt factory as it is the offshored, globalized clean-room assembly of micro-chip (even now an anachronistic metaphor for the production of smartphones and all the associated computer and electronic hardware. (see Google-Chrome, Amazon-Kindle, Microsoft-Surface, Apple iPhone)

And then there’s CTM dynamic information/data communication content for the form(s) carrying the message(s)...the metaphorical fuel/blood for the rolling stock produced and circulating in the CTM factory as it sits within a circuit of capital as it generates commodities.

The dynamic elements are the organic labor forces holding and activating this Virtual, Human, Inorganic/organic Capital

Cultural production and the political economy of violence has commodity implication not only in the production of instruments of death like firearms but the production of meaning and messages that promote death as a commodity. These are components of a political economy of commodity/signs The political economy of networks are the dynamic accumulation of contingent knowledge capital and are as Castells has described networked capital as a space of flows (flow infrastructure (abstract)) carried on (stock infrastructure (concrete)).

www.polecom.org/...Corporate social media (Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Weibo, Blogspot, LinkedIn etc.) all use a business model that is based on targeted advertising that turns users’ data (content, profiles, social networks and online behaviour) into a commodity. Commodities have producers who create them, otherwise they cannot exist. So, if the commodity of internet platforms is user data, then the process of creating this data must be considered to be value-generating labour. Consequently, this type of internet usage is productive consumption or prosumption in the sense that it creates value and a commodity that is sold. Dallas Smythe’s concept of the audience commodity has been revived and transformed into the concept of the internet prosumer commodity (Fuchs, 2012). Digital labour creates the internet prosumer commodity that is sold by internet platforms to advertising clients. They in return present targeted ads to users.

Digital labour on “social media” resembles housework because it has no wages, is mainly conducted during spare time, has no trade union representation, and is difficult to perceive as being labour. Like housework it involves the “externalization, or ex-territorialization of costs which otherwise would have to be covered by the capitalists” (Mies, 1986: 110). The term ‘crowdsourcing’ (Howe, 2009) expresses exactly an outsourcing process that helps capital to save on labour costs. Like housework, digital labour is “a source of unchecked, unlimited exploitation” (Mies, 1986: 16). Slaves are violently coerced with hands, whips, bullets—they are tortured, beaten or killed if they refuse to work. The violence exercised against them is primarily physical in nature. Houseworkers are also partly physically coerced in cases of domestic violence. In addition, they are coerced by feelings of love, commitment and responsibility that make them work for the family. The main coercion in patriarchal housework is conducted by affective feelings. In the case of the digital worker, coercion is mainly social in nature. Large platforms like Facebook have successfully monopolised the supply of certain services, such as online social networking, and have more than a billion users. This allows them to exercise a soft and almost invisible form of coercion through which users are chained to commercial platforms because all of their friends and important contacts are there and they do not want to lose these contacts. Consequently, they cannot simply leave these platforms.

In a passage in the Grundrisse, Marx (1939/1973: 462) makes clear the various components of alienation within capitalism. The worker is alienated from herself/himself because labour is controlled by capital, the material of labour, the object of labour and the product of labour. These four components of alienation can be related to a labour process that, in a Hegelian sense, consists of a subject, an object and a subject-object. We are talking here about alienation of the subject from itself (labour-power is put to use for and is controlled by capital), alienation from the object (the objects of labour and the instruments of labour) and from the subject-object (the products of labour).

All workers that are exploited by capital are alienated from the products of their work. In corporate social media, alienation takes on a specific form. Users are objectively alienated because in relation to subjectivity they are coerced by isolation and social disadvantage if they leave monopoly capital platforms (such as Facebook). In relation to the objects of labour, their human experiences come under the control of capital. In relation to the instruments of labour, the platforms are not owned by users, but by private companies that also commodify user data. In relation to the product of labour, monetary profit is individually controlled by the platform’s owners. These four forms of alienation together constitute capital’s exploitation of digital labour in corporate social media.

The problem for research is situating it in the circuit of capital with the issues of articulation of those institutional elements manifested as the social media conflicts demonized in the attacks on so-called “cultural marxism” wherein the Cold War memes return despite the family resemblances among state capitalisms in the West and East(sic).

Grand Hotel Abyss By Stuart Jeffries Verso: September 2016 reviewed by Robert Minto (August 1, 2016)

In the late 20th and early 21st century, this strategy of Aesopian language backfired in a big way. On the paranoid right, the Frankfurt School has become a boogieman, the object of “a conspiracy theory that alleges that a small group of German Marxist philosophers […] overturned traditional values by encouraging multiculturalism, political correctness, homosexuality and collectivist economic ideas.” The strategy of Aesopian language makes the Frankfurt School look sly, whereas, Jeffries implies, it was just ineffectual:

The leading thinkers of the Institute for Social Research would have been surprised to learn that they had plotted the downfall of western civilisation, and even more so to learn how successful they had been at it.

According to Jeffries, the Frankfurt School latched onto the ideas of alienation through reification and made it the basis for their whole method of criticizing society. This was a power move because the manuscripts in which Marx had most fully discussed these ideas, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, were being published for the first time just when the Frankfurt School thinkers came into their own. But whereas Marx seemed to think reification of labor happened occasionally and to some people (the most exploited of wage-laborers), the members of the Frankfurt School proposed to think of it as a pervasive, inescapable social condition...

Under capitalism, according to them, we could interpret the objects onto which we projected our reified selves as if they were a collective unconscious. We could talk about fire trucks and merry-go-rounds and bonsai trees in a way that illuminated our own displaced problems...

Benjamin hoped that his kind of writing would be, as Jeffries puts it, “a kind of Marxist shock therapy aimed at reforming consciousness,” waking people up to the dream-world they lived in under capitalism. But along with the other thinkers of the Frankfurt School, he seemed to deny the possibility of any escape from that dreamworld. “This was to become one great theme of critical theory,” writes Jeffries: “there is no outside, not in today’s […] totally reified, commodity-fetishising world.” Or, as Benjamin more memorably put it, “There has never been a document of culture which is not simultaneously one of barbarism.”

Comments

Couldn't make heads nor

tails. Near as I could discern, the entire internet is an organ of misinformation; everything we see and hear from the MSM is a load of horse$h!t. And Russia and Karl Marx somehow involved. Something like that.

the little things you can do are more valuable than the giant things you can't! - @thanatokephaloides. On Twitter @wink1radio. (-2.1) All about building progressive media.

Rather a lot to absorb,

Rather a lot to absorb, although thanks for the intensive labour going into this. This is something I'll need to get back to when feeling a bit livelier, not having the background or currently the mental acuity to even make the necessary connections I'm sure that I'm missing.

Psychopathy is not a political position, whether labeled 'conservatism', 'centrism' or 'left'.

A tin labeled 'coffee' may be a can of worms or pathology identified by a lack of empathy/willingness to harm others to achieve personal desires.

Jeebus. Words, words, lots of words.

Words like hegemonic, quintessential, epiphenomenal, dialectical, a (Badiou) extensional network, reify, dichotomous, disintermediated, valorization. These aren't even the block-quoted parts.

I edit college-level and some graduate-level textbooks and they aren't usually this dense with multiple syllables.

All to say that the media lies and Trump is ahead because Russia is helping him? It's not because Clinton is a terrible candidate and probably also a terrible person?

If that's not your point, then I missed it in the verbiage.

OK, you're smart. Or have a serious way with a thesaurus. I still think Clinton is losing to/tied with Trump because she's terrible, and Russia is irrelevant.

Whew. My eyes hurt.

Please check out Pet Vet Help, consider joining us to help pets, and follow me @ElenaCarlena on Twitter! Thank you.