Negative interest rate blowback

The insanity of negative interest rates is one of the most under-reported, under-appreciated developments in recent days.

For instance, consider this.

JPMorgan Chase recently sent a letter to some of its large depositors telling them it didn’t want their stinking money anymore. Well, not in those words. The bank coined a euphemism: Beginning on May 1, it said, it will charge certain customers a “balance sheet utilization fee” of 1 percent a year on deposits in excess of the money they need for their operations. That amounts to a negative interest rate on deposits. The targeted customers—mostly other financial institutions—are already snatching their money out of the bank. Which is exactly what Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon wants. The goal is to shed $100 billion in deposits, and he’s about 20 percent of the way there so far.

Pause for a second and marvel at how strange this is. Banks have always paid interest to depositors. We’ve entered a new era of surplus in which banks—some, anyway—are deigning to accept money only if customers are willing to pay for the privilege.

Because of negative interest rates, big banks are looking to shed their retail operations altogether. HSBC is in the process of getting out of retail banking altogether.

Think for a second how this turns every idea you've ever had about the world of finance on its head: banks no longer want your money.

What's more, they are looking to dump large depositors first.

It just keeps getting more bizarre. This is especially true in Europe...

Now, €2.8 trillion of eurozone debt offers a negative yield, according to BofA Merrill.

Only six weeks into the European Central Bank’s €1 trillion-plus ($1.07 trillion-plus) bond-buying program, more than half of the eurozone government-debt market now offers investors a negative yield.

What's more, more than half of all government debt in the world is yielding less than 1%. This is disastrous for anyone wanting to retire.

It also is having bizarre outcomes that people would never imagine just a few short years ago.

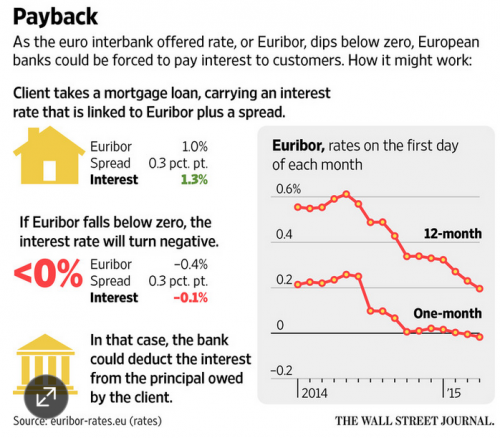

Tumbling interest rates in Europe have put some banks in an inconceivable position: owing money on loans to borrowers.

At least one Spanish bank, Bankinter SA, the country’s seventh-largest lender by market value, has been paying some customers interest on mortgages by deducting that amount from the principal the borrower owes.

The reason is because many mortgages are based on the Euribor, and that index has just gone negative.

For a long time negative interest rates were considered impossible. Why would you pay someone to loan them money? It makes no sense. Well, there are short-term reasons that make sense.

First, negative yields may make sense if you expect a significant decline in prices. Under deflation, real (or inflation-adjusted) yields could be positive even if nominal yields are negative.

Second, yields may become even more negative, which allows for profit potential for those willing to sell before maturity.

So as a momentum trade it makes sense. The problem is what happens when that momentum ends?

Chances are that when things get so bizarre that you can't understand them, then you aren't crazy.

Interest rates have been driven down to this level by central banks that want you to borrow and spend. But negative interest rates and global deflation, which has been at least partly caused by the central bank policies, has caused a paradox: People are going to take money out of the bank and store it somewhere.

Which leaves central banks and their governments the options of stopping what they are doing, or doubling down.

Bank notes, as an alternate storehouse of value, are a constraint on central banks’ power. “We view this constraint as undesirable,” Citigroup Global Chief Economist Willem Buiter and a colleague, economist Ebrahim Rahbari, wrote in an April 8 research piece. They laid out three ways that central banks could foil cash hoarders: One, abolish paper money. Two, tax paper money. Three, sever the link between paper money and central bank reserves.

Getting rid of cash would also undermine the underground economy, so that seems to be the most likely next step.

Comments

Do they know what the hell they are doing?

I had a money market account with one of the investment companies. They were charging me a 6% something for the privilege. Every time I got my statement, it was worth less than the statement before. I dumped that really quick. Is it the trillions they have off-shored?

"Religion is what keeps the poor from murdering the rich."--Napoleon

I don't believe they do

I think that we've gone into the realm of "experimental monetary policy".

And it's because our political system is incapable of reforming the banking industry.

"experimental monetary policy" Holy Crap Batman

Any thoughts on those that recently retired? My parents for one......

FDR 9-23-33, "If we cannot do this one way, we will do it another way. But do it we will.

Thanks for a thought provoking essay.

So, is all the money being driven into bonds (debt) or asset ownership or speculative investments?

You helped me see where the end of cash fits in, though.

Are we all going to get bio-chipped?

Smells like Bible spirit: Revelation 13:11–17

Verse 13: air-to-surface missile attacks / drones?

Verses 14–15: mass media / mass surveillance?

Verses 16–17: abolition of cash / biochip required for trade?

Priceless!

Thanks for the smile, lotlizard.