Friday Open Thread ~ "What are you reading?" edition. Volume 3

For today's open thread, we'll be looking at the world through the eyes of one of my favorite authors:

Barry Lopez, in full Barry Holstun Lopez, (born January 6, 1945, Port Chester, New York, U.S.), American writer best known for his books on natural history and the environment. In such works as Of Wolves and Men (1978) and Arctic Dreams: Imagination and Desire in a Northern Landscape (1986; National Book Award), Lopez employs natural history as a metaphor for wider moral issues.

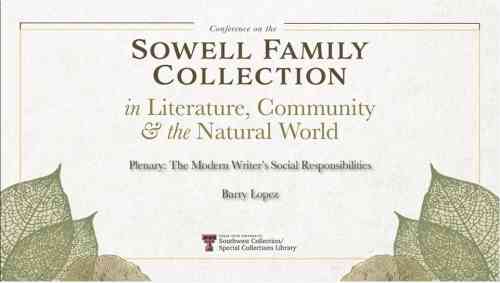

Lopez also has a special place in my heart because my alma mater, Texas Tech University, has designated him their first scholar in residence. In that role, Barry spoke in Lubbock about the modern writer's social responsibilities.

[video:https://youtu.be/EqCTdxnSkME?t=310]

After graduating from the University of Notre Dame (B.A., 1966; M.A.T., 1968), Lopez briefly attended the University of Oregon before leaving to become a full-time writer. In 1977 Lopez’s collection of Native American trickster stories, Giving Birth to Thunder, Sleeping with His Daughter: Coyote Builds North America, was published. He followed this volume with the critically acclaimed Of Wolves and Men, which includes scientific information, folklore, and essays on the wolf’s role in human culture.

Lopez also wrote such fictional narratives as Desert Notes: Reflections in the Eye of a Raven (1976) and River Notes: The Dance of Herons (1979). Among his short-story volumes were Winter Count (1981), Light Action in the Caribbean (2000), and Outside (2014). Other notable works included the essay collections Crossing Open Ground (1988) and About This Life (1998). In Horizon (2019) Lopez recounted his various travels. In addition, he authored books for young adults on natural history.

Since this is free range political blog site, we'll step outside the nature writing genre for which he is well known and examine a side of Barry Holstun Lopez that receives less attention.

>

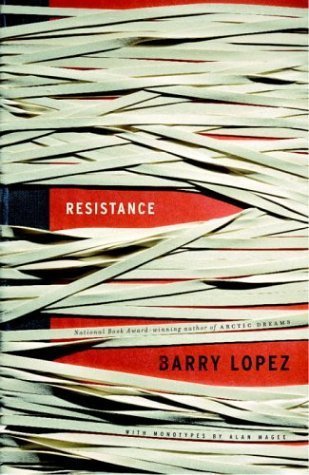

"...a highly charged, stunningly original work of fiction -- a passionate response to the changes shaping our country today. In nine fictional testimonies, men and women who have resisted the mainstream and who are now suddenly 'parties of interest' to the government tell their stories.

A young woman in Buenos Aires watches bitterly as her family dissolves in betrayal and illness, but chooses to seek a new understanding of compassion rather than revenge. A carpenter traveling in India changes his life when he explodes in an act of violence out of proportion to its cause. The beginning of the end of a man's lifelong search for coherence is sparked by a Montana grizzly. A man blinded in the war in Vietnam wrestles with the implications of his actions as a soldier -- and with innocence, both lost and regained.

Punctuated with haunting images by acclaimed artist Alan Magee, Resistance is powerful fiction -- Barry Lopez at his best."

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

- Apocalypse

- Río de la Plata

- Mortis and Tenon

- Traveling With Bo Ling

- The Bear in the Road

- The Walls at Yogpar

- Laguna de Bay in A-Sharp

- Nilch’i

- Flight from Berlin

The Complete text of "Apocalypse"

I remember the morning the letter came. I left the apartment Mary and I were renting on rue Lepic and strolled in the sunshine up to rue des Abbesses. The old sidewalks were freshly washed, the air was still cool. My regular way was to get a morning paper, a brioche, and black coffee and then sit in the little park by the Metro station and read. Sometimes I would walk up Yvonne-le-Tac to the terraced park below Sacré Coeur instead, but that morning I had that fistful of mail.

We took the apartment partly because it was right around the corner from the cemetery in Montmartre. Mary was writing an essay about the cemeteries of France for Harper's, a history of how they had been disrupted and desecrated by revolution, but the expansion of cities, and of course by the Church. The Cimetière de Montmartre was palpable, a reassurance to her. Many of its graves had been destroyed in 1789, the bodies treated like so much trash by those who had hated royalty and aristocracy, and by the hoodlums who always attach themselves to social change. But Degas is buried there, the composer Berlios, Nijinsky, and her favorite, Adolphe Sax, the inventor of the saxophone.

It was not these ghosts, though, nor the untroubled allées colonnaded by plane trees, hat calmed her. It was that the stillness sheltered an aggregation of mute evidence, apparent throughout the city in its small-scale neighborhoods, that our history is finally human. Regimes and ideologies -- Tamerlane's Mongol empire, Caligula's Rome, Stalin's Soviet Union -- whatever their horrors, whatever afflictions they deliver, pass away. What endures is simple devotion to the question of having been alive. The cemetery comforted her because it was not about death but about transcendent joie de vivre.

One day she returned to the apartment and read me an inscription she'd copied from a gravestone. Ma gracieuse spouse. . . A husband had expressed his love and regard for his wife of fifty-one years in a few bare, unselfconscious sentences. Mary sat with the piece of paper in her hand by the open window, watching patrons in the bistro across the street talking and hailing friends passing on the sidewalk, and turned a shoulder so I could not see her crying.

Her tears, I thought, were over a kind of loss we had talked about in recent weeks, the way the fabric of love scorches, no matter how vigilant we are. The intricate nature of the emotions men and women exchange made the two of us sense our own endangerment when we disagreed; but we had also been speaking of the ephemeral love one can feel toward a complete stranger, for the way they step of a sidewalk or a father hands his daughter her gloves at the door. Bound together in these many ways we are still swept suddenly out of each other's lives, by tides we don't recognize and tides we do. The sensation of loss, the weight of grief, the feeling of being naked to a menace are hard to separate. The fear of an outside force at work makes us reticent in love, and suspicious. We identify enemies.

The instruments of discord show up family in our lives, of course, demanding our attention. The unscrupulous peer, the woman on the make, the purblind enforcer, the self-annointed official and his cronies, people with a craving for confrontation. We are foolish to give any of them what they ask for, and we betray ourselves and anyone toward whom we have ever felt tender by not sending such people immediately on their way.

The first two pieces of mail I opened that morning were letters from museums, one in Rouen, the other in Orleans. At the time, I was trying to assemble work by European artists which had been shaped by their experience with le Maquis, the French underground, for a show to open at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and then to travel around the United States. The communications were about insuring the works the museums were lending. I read each one with relief as, sentence by sentence, they eliminated the risks on my part. I should have known -- the consideration.

The rest of the mail was personal -- friends and family, some items of business for Mary. The one letter I put off reading sat all the while on the green slats of the bench while I finished perusing the paper. The envelope had the look of something you might be sent by the Internal Revenue Service, carrying news of an irregularity in your filings, a notice of additional tax due, perhaps a penalty. But the letter was from another federal authority, a branch of our government but a few years old though already monolithic. Its special charge was to make the nation safe from attack by a great array of vaguely defined "terrorists," domestic and foreign. This work it pursued with religious fervor and special exemptions form the Department of Justice.

I read the letter twice, concealed it in the half fold of Le Monde, and walked back to the apartment. Mary was in her robe, making breakfast. I handed her the letter and took her place at the stove.

She read it in the chair by the window.

"I will never get used to this hyperbolic crap," she said, folding the letter back up. "Every racist step they take, you expect people to laugh in their faces, just take their toys away, you know -- the guns and the new laws. Do they just not register the suspicion, the resentment in half the streets in the world?"

She turned abruptly to look out the window, as if responding to someone down there on the sidewalk. Incomprehension, exhaustion, fear passed behind her eyes. She let the letter drop to the floor as if it were an advertising circular.

"I can't believe we have to take people like this seriously, Owen."

I put breakfast on the table, refreshed her coffee, and came back with my laptop. I began e-mailing a loose network of people I'd been in regular touch with since the change of administration took place in our country. We communicated through a series of codes and used electronic back doors which delayed exchanges, but by mid-morning I'd confirmed what I had suspected. The letter had gone to everyone.

It came from Inland Security, the group of people we had come to call the Idiots of Light, for the way they are dazzled by their god. Their ranks include people who celebrate the insults of advertising and the deceptions of public relations campaigns as paths to redemption. The letter also originated with the Division of Economic Equality, those in the Department of Commerce we call the Lottery Enforcers, who argue for the calming and salutary effect of regular habits of purchase. And it bore the gold, eagle-talon insignia of the Delta Confederacy, the contingent of citizen groups that reports to the education staff of the Office of Inland Security.

The letter's authors informed us of the nation's persisting need for democratic reform. Each of us was told of widespread irritation with our work, and the government's desire to speak with us.

The authority behind the letter -- two crisply printed cream-colored sheets of laid paper with signatures in red ballpoint -- made my breath shudder. I sat watching for incoming e-mail. We hadn't anticipated this, not exactly this frontal an approach.

After university I and my friends had scattered abroad -- to Brussels, Caracas, Sapporo, Melbourne, Jakarta, any promising corner. Two or three went deep upriver on the Orinoco or out onto the plateaus of Tibet and Ethiopia. We had come to regard the work of writers and artists in our country as too compliant, as failing to expose or indict the escalating nerve of corporate institutions, the increasing connivance of government with business, or the cowardice of those reporting the news. In the 1970s and '80s, we thought of our artists and writers as people gardening their reputations, while the families of our neighborhoods disintegrated into depression and anger, the schools flew apart, and species winked out. It was the triumph of adolescence, in a nation that wanted no part of its elders' remonstrance or any conversion to their doubt.

The years passed. We had no plan. We had no hope. We had no religion. We had faith. It was our belief that within the histories of other, older cultures we would find cause not to be incapacitated by the ludicracy of our own. It was our intuition that even in those cultures into which our own had injected its peculiar folklore -- that success is financial achievement, that the future is better, that life is an entertainment -- we would encounter enduring stories to trade in. We thought we might be able to discern a path in stories and performances rooted in disparaged pasts that would spring our culture out of its adolescence.

This remains to be seen. We stay in close touch (a modern convenience), scattered though we are. And now others, of course, keep close watch on us, on what we write and say, on whom we see. We are routinely denounced by various puppet guards at home, working diligently for a prison system we don't believe in. As the days have mounted, though, we've tasted more of the metal in that system's bars.

We feel cold.

Our goal is simple: we want our country to flourish. Our dilemma is simple: we cannot tell our people a story that sticks. It is not that no one believes what we say, that no one knows, that none of our countrymen cares. It is not that their outspoken objections have been silenced by the rise at home of local cadres of enforcement and shadow operatives. It is not that they do not understand. It is that they cannot act. And the response to tyranny of every sort, if it is to work, must always be this: dismantle it. Take it apart. Scatter its defenders and its proponents, like a flock of starlings fed to a hurricane.

Our strategy is this: we believe if we can say what many already know in such a way as to incite courage, if the image or the word or the act breaches the indifference by which people survive, day to day, enough will protest that by their physical voices alone they will stir the hurricane.

We're not optimistic. We chip away like coolies at the omnipotent and righteous façade, but appear to ourselves as well as others to be ineffective dissenters. We've found nothing to use against tyranny that has not been written down or danced out or sung up ten thousand times. It is the somnolence, the great deafness, that reveals our problems. It is illiteracy. It is an appetite for distraction, which has become a cornerstone of life in our nation. In distraction one encounters the deaf. In utter distraction one discovers the refuge of illiteracy.

And here is nearly the bitterest of blunt issues for us: What can love offer that cannot be rejected? What gesture cannot be maligned as witless by those who strive for every form of isolation? When we were young, each of us believed that to love was to die. Then we believed that to love was essential. Now we believe that without love our homeland -- perhaps all countries -- will perish. Over the years, as we have learned what it might mean to love, we have generally agreed that we've better understood the risks. In our nation, it is acceptable to resent love as an interference with personal liberty, as a ruse the emotions employ before the battlements of reason. It is the abused in our country who now most weirdly profess love. For the ordinary person, love is increasingly elusive, imagined as a strategy.

We reject the assertion, promoted today by success-mongering bull terriers in business, in government, in religion, that humans are goal-seeking animals. We believe they are creatures in search of proportion in life, a pattern of grace. It is balance and beauty we believe people want, not triumph. The stories the earth's peoples adhere to with greatest faith -- the dances that topple fearful walls; the ethereal performances of light, color, and music; the enduring musics themselves -- are all well patterned. And these templates for the maintenance of vision, repeated continuously in wildly different idioms, from the eras of Lascaux and Shanidar to the days of the Prado and Butoh, these patterns from the artesian wells of artistic impulse, do not require updating. They require only repetition. Repetition, because just as murder and infidelity are within us, so, too, is forgetfulness. We forget what we want to mean. To achieve progress, we've all but cut our heads off.

We found the Inland Security letter ridiculous, but also alarming. It declared that, as none of us had renounced his or her citizenship, we would be interrogated as nationals "with the full cooperation of the stewards of democracy in your host countries." We might then be indicted; or dismissed and ignored; or possibly turned over to local authorities, "some of whom," we were advised, "might have no regard for due process, the writ of habeas corpus, or other advancements in law which are found in civilized countries." The disposition of our cases, it was made clear, would not be at our discretion.

Our stratagems, the letter continued, were those typical of "terrorist cells." They called for scrutiny; and we had to desist. We were reminded, then, not any longer to circulate those texts, images, music, and films already listed as anti-democratic in monthly bulletins from the Select Committee on the Arts, an innovation of the Offices of the President. Or any artistic or literary works created by cultures "inimical to our nation's policies." To achieve wealth, the letter informed us, is the desire of all peoples everywhere; and while our nation was working to establish wealth for all peoples everywhere, resistance like ours, a quibbling over methods, actually created poverty.

The letter explained, in phrases that bore the brushstrokes of zealots and lawyers, that we were to be sought out, quizzed, and possibly punished or isolated from society, because we "were terrorizing the imaginations of our fellow citizens" with our books, paintings, and performances. Sojourning, some of us, with "unadvanced" cultures, attending to their myths and stories, along with making inquiries into primitive or revolutionary art, had poisoned our capacity to understand civilization's triumphs. We were attempting to resurrect the past and have it stand equal with the present. We profoundly misunderstood, our accusers argued, the promise of the future. We were offering only darkness where for some centuries the fires of freedom had been blazing, the beacons of prosperity increasing in their intensity.

The letter implied that there was still hope for us, however. The interrogations, the extraditions, trials, and incarcerations-these need not follow a predictable course. Apology, if of the most profound sort, was a possibility. Reeducation was an option. Missionary work, yet another possibility. In a democracy, the acknowledgment of one's errors, coupled with a suitable penance, could leave an individual with a very bright future. Some, inevitably, would have to face harsh punishment for fooling with the country's destiny.

The human imagination, the letter speculated, was a problematic force, its use best left to experts. An imagination in the wrong hands, missing the guidance of democratic reasoning and fed the wrong ideas, an imagination with no measure of economic awareness, was a loose cannon.

The combustible nature of the communiqué, its rhetorical gibberish, its Draconian suspicions, its headlong theorizing, its fear of contradiction were all of a piece -- fundamentalism's rave and can't. That our government had succeeded in reading each of us with such a letter, considering the deluge of volunteers among domestic antiterrorist groups who had responded to its call for administrative help, was no surprise. What surprised us was that we mattered to this degree, that we represented a serious threat.

The dispatch, then, made us think. It made us wonder if that leap of faith by which we had lived each day, and according to which every citizenry would outlive its tyrants, was not a more valid belief than we had supposed.

The contents of the letter galvanized each of us. In that small apartment on rue Lepic that morning, Mary and I made a decision, which we then communicated to our friends in Alice Springs and elsewhere. When we had read their responses, we packed.

We are not to be found now. We have unraveled ourselves from our residences, our situations. But like a build in a basement, suddenly somewhere we will turn on again in darkness. We will carry what we know -- what it can mean to have your country under you like a hammock, what it is to take part in the world instead of using your people as fodder in a war to control the world's meaning and expression -- we'll carry all of this into other countries. It will be hidden in our individual skills, in our dress, our speech and manner, in the memory of each one of us. The memory of one will kindle the memory of another, a burst of electricity across a chasm. We will disrupt through witness, remembrance, and the courtship of the imagination. We will escort children past the darkest warrens of the forest. We will construct kites that stay aloft in the rain. We will champion what is beautiful, and so finally make our opponents irrelevant.

For all we know our interrogators are already airborne, or checking through customs, scouring phone books, hiring boats to take them quickly upriver. They will be packing satellite phones, PalmPilots, and GPSs, local dictionaries, Lonely Planet guides, open bank drafts, automatic pistols, Dexedrine, Visa cards, Kaopectate, Xanax, cocaine, letters of proprietary claim from NLog Communications, and cartons of Marlboros for the purposes of barter. They will get where they are going but we will not be there. They will find instead these stories of where we have been and what we have seen.

In place of ourselves we offer the written documents that follow, partly out of a simple respect for each agent's arduous journey, but with an intuition also about his or her misgivings, and with compassion for the many troublesome addictions that afflict the emissary sent on an errand of violence.

To these loyal marshals' distant master we concede this: we understand you mean us no good, that you are cunning, and that you have the support of many in our country who regard works of the imagination unreviewed by your committees as disruptions in the warm stream of what pleases them -- product availability, job advancement, pretty scenery, buying a ticket that wins. We will not describe or attempt to defend the lives that may recently have brought each of us to your attention, being wary of what you will make of them in consultation with the national media. I have asked the other recipients of your letter instead to recall the moment in which they recognized the transformation that led to the work that so infuriated you -- Lisa Meyer's installation AdSpeak, when it opened in Toronto; Susan Begay's mural of the terrorist Kit Carson's depredations at Canyon de Chelly; Eric Rutterman's translations of Tukano mythology and the play Emilio Chavez developed from them, which opened at the Mark Taper in Los Angeles; the private correspondence of Corazon Aquino edited by Jefferson deShay, which so embarrassed your predecessors.

Instead of a defense of the Republic, thrown in the corporate face of your governance, instead of another map to the kingdom of your frauds, an exposé of your pursuit of the voter as a mail-order customer, we give you a description of the events that changed us, that led to our decisions to no longer be silent, no longer to hunker down in the small rooms of our lives.

It is also our intention to break these stories out ahead of your avenging fist, to get them, through the agency of a sympathetic and defiant publisher, directly into the hands of men and women who stand at similar thresholds, before you stifle their initiative with your intimidations.

We regard ourselves as servants of memory. We will not be the servants of your progress. We seek a politics that goes beyond nation and race. We advocate for air and water without contamination, even if the contamination be called harmless or is to be placed there for our own good. We believe in the imagination and in the variety of its architectures, not in one plan for all, even if it is God's plan. We believe in the divinity of life, in all its human variety. We believe that everything can be remembered in time, that anyone may be redeemed, that no hierarchy is worth figuring out, that no flower or animal or body of water or star is common, that poetry is the key to a lock worth springing, that what is called for is not subjugation but genuflection.

We trace the line of our testament back beyond Agamemnon, past Ur, past the roots of the spoken to handprints blown on a wall. We cannot be done away with, any more than the history of the Sung dynasty can be done away with, traveling as it does as a beam of coherent light far beyond our ken. We cannot, finally, be imprisoned or killed, because we remember and speak.

We are not twelve or twenty but numerous as the motes of dust lining the early morning shafts of city light. We are unquenchable and stark in the same moment that we are ordinary. We incorporate damage and compassion, exaltation and weariness-to-the-bone.

These pages are our response to your intrusion, your order to be silent, your insistence that we have something to talk over.

Owen Daniels, independent curator,

author, Commerce and Art in America,

on leaving Paris

Comments

(No subject)

Few are guilty, but all are responsible.”

― Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Prophets

Thanks for sharing this Philly blue

looks like an interesting read

truth is sometimes found in fiction

a good author can make the reader think

beyond comfortable considerations

cheers

question everything

Craig Hodges....an easy read, very pertinent in todays world

https://www.haymarketbooks.org/books/964-long-shot

I never knew that the term "Never Again" only pertained to

those born Jewish

"Antisemite used to be someone who didn't like Jews

now it's someone who Jews don't like"

Heard from Margaret Kimberley

John Lewis

From NYT

Mr. Lewis, the civil rights leader who died on July 17, wrote this essay shortly before his death, to be published upon the day of his .

While my time here has now come to an end, I want you to know that in the last days and hours of my life you inspired me. You filled me with hope about the next chapter of the great American story when you used your power to make a difference in our society. Millions of people motivated simply by human compassion laid down the burdens of division. Around the country and the world you set aside race, class, age, language and nationality to demand respect for human dignity.

That is why I had to visit Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, though I was admitted to the hospital the following day. I just had to see and feel it for myself that, after many years of silent witness, the truth is still marching on.

Emmett Till was my George Floyd. He was my Rayshard Brooks, Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor. He was 14 when he was killed, and I was only 15 years old at the time. I will never ever forget the moment when it became so clear that he could easily have been me. In those days, fear constrained us like an imaginary prison, and troubling thoughts of potential brutality committed for no understandable reason were the bars.

Listen to This Op-Ed

Audio Recording by Audm

Though I was surrounded by two loving parents, plenty of brothers, sisters and cousins, their love could not protect me from the unholy oppression waiting just outside that family circle. Unchecked, unrestrained violence and government-sanctioned terror had the power to turn a simple stroll to the store for some Skittles or an innocent morning jog down a lonesome country road into a nightmare. If we are to survive as one unified nation, we must discover what so readily takes root in our hearts that could rob Mother Emanuel Church in South Carolina of her brightest and best, shoot unwitting concertgoers in Las Vegas and choke to death the hopes and dreams of a gifted violinist like Elijah McClain.

Like so many young people today, I was searching for a way out, or some might say a way in, and then I heard the voice of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on an old radio. He was talking about the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence. He said we are all complicit when we tolerate injustice. He said it is not enough to say it will get better by and by. He said each of us has a moral obligation to stand up, speak up and speak out. When you see something that is not right, you must say something. You must do something. Democracy is not a state. It is an act, and each generation must do its part to help build what we called the Beloved Community, a nation and world society at peace with itself.

Ordinary people with extraordinary vision can redeem the soul of America by getting in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble. Voting and participating in the democratic process are key. The vote is the most powerful nonviolent change agent you have in a democratic society. You must use it because it is not guaranteed. You can lose it.

You must also study and learn the lessons of history because humanity has been involved in this soul-wrenching, existential struggle for a very long time. People on every continent have stood in your shoes, through decades and centuries before you. The truth does not change, and that is why the answers worked out long ago can help you find solutions to the challenges of our time. Continue to build union between movements stretching across the globe because we must put away our willingness to profit from the exploitation of others.

Though I may not be here with you, I urge you to answer the highest calling of your heart and stand up for what you truly believe. In my life I have done all I can to demonstrate that the way of peace, the way of love and nonviolence is the more excellent way. Now it is your turn to let freedom ring.

When historians pick up their pens to write the story of the 21st century, let them say that it was your generation who laid down the heavy burdens of hate at last and that peace finally triumphed over violence, aggression and war. So I say to you, walk with the wind, brothers and sisters, and let the spirit of peace and the power of everlasting love be your guide.

my bold

question everything

Good morning Philly. When I get a change to read print,

I work on my pile of non-fiction magazines; sky & telescope, american archaeology, scientific american, popolar science, and the like, sad to say. "Apocalypse" was an interesting read, quasi fiction, quasi prophecy and quasi recitation of current history. Interesting in the same way that we live in interesting times.

thanks.

be well and have a good one.

That, in its essence, is fascism--ownership of government by an individual, by a group, or by any other controlling private power. -- Franklin D. Roosevelt --

Thank you phillybluesfan,

for introducing Barry Lopez. I've listened so far to half of his talk at the sowell conference. He's very inspiring, and I am happy to finally meet a fellow resident of Port Chester. I grew up there from age 6-15. He reminds me of Jon Kabat-Zinn - https://www.mindfulnesscds.com

Enjoy the weekend

Thanks also for the reference to Alan Magee

I've enjoyed looking at his paintings ...

.

I saw your essay yesterday

but didn't have a chance to comment. I'm a Barry Lopez fan and read his Rediscovery of North America last summer. I'm putting Resistance at the top of my to-read list. Thank you for that excerpt.

I watched the first video clip you posted...the talk at Texas Tech. I'll watch the second video when I get a chance, I'm looking forward to it.

Another book on my to-read list is the new graphic book out by Joe Sacco. It is called Paying The Land. Chris Hedges did an interview with Sacco which you may find interesting.

Thanks for your 'Reading' column... I enjoyed it very much.