The impact of the bond market crash

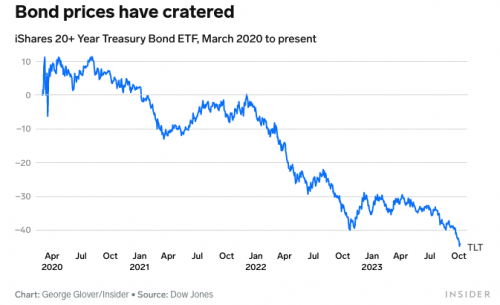

I posted this chart earlier this week, but a lot of people were confused what it meant, so I'm going to expand on this.

Some people thinks this is no big deal. This is a huge mistake. To give you some idea, consider this chart.

You might think that a market crash would obviously mean someone was taking massive losses, but for some people this is still a surprise. The bond market is at least twice as big as the stock market. so a crash here would have a much larger impact.

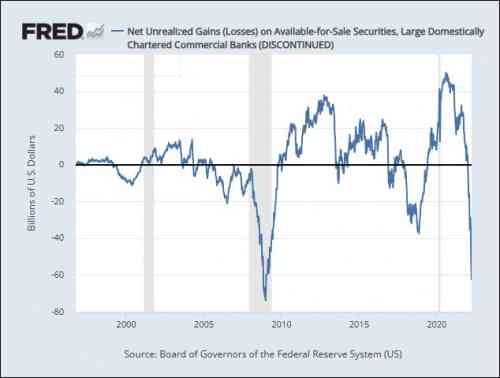

On March 30, 2022, two highly troubling events occurred: (1) Fed data showed that unrealized losses on available-for-sale securities at the 25 largest U.S. banks were approaching the levels they had reached during the financial crisis in 2008; and (2) the Fed simply stopped reporting unrealized gains and losses on these banks’ securities.As the chart above indicates, the Fed had reported this data series from October 2, 1996 to March 30, 2022 – and then, poof, it was gone and could no longer be graphed weekly at FRED, the St. Louis Fed’s Economic Data website. (See chart above from FRED.) On the same date, the Fed also discontinued the weekly data for unrealized losses or gains on available-for-sale securities at all commercial banks and small banks.)

When they stop measuring the data as it turns to sh*t, that should tell you something.

I want to point out another less obvious development from the market crash which just shows you how the bankers are in over there heads.

On September 21, the U.S. Treasury’s Assistant Secretary for Financial Markets, Josh Frost, delivered a speech in which he indicated that “we expect that further gradual increases in coupon auctions sizes will likely be necessary in future quarters.”Frost also indicated that the Treasury is, apparently, going to join the thinking of the wizards at the Wall Street mega banks who prop up their banks’ share prices by spending tens of billions of dollars a year buying back their own stock. Frost shared the following with his audience:

“After careful consideration, we decided it was prudent to move forward and announced our intentions at the May refunding to implement a regular buyback program next year. We believe buybacks can play an important role in helping to make the Treasury market more liquid and resilient by providing liquidity support. The buyback program will also help Treasury to better achieve our debt management objectives….”

Which means that a new buyer of last resort for Treasury securities is needed. But should that really be the same entity that is issuing the debt in the first place? If the Treasury has the money to buy back its debt, why is it issuing the debt? Adding to the double speak, Frost said this during his speech on September 21:

“While we believe it is important that we retain some flexibility in providing incremental liquidity support to certain sectors of the Treasury market, it is important we make it clear at the outset that these buybacks are not intended to ameliorate periods of acute market stress. Unlike the Federal Reserve System, which can finance purchases of securities by creating reserves, each dollar of buybacks needs to be financed with a dollar of Treasury issuance, all else equal. This limits our ability to rapidly increase the size of buybacks to a level potentially necessary to alleviate market stress without resulting in significant costs for the taxpayer, as a corresponding rapid rise in Treasury issuance could materially increase our financing costs during these periods.”

Buybacks. Brilliant! Maybe they should also issue themselves bonuses and complete the picture.

Remember, as interest rates go up, the price of existing bonds goes down. This is especially bad for developing world nations, that have to borrow in dollars.

According to some estimates, almost 60 percent of the poorest countries are either in or at high risk of debt distress, nearly doubling since 2015 (Figure 1; World Bank 2022a). Total debt service payments on public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) external debt of the poorest countries rose to over $50 billions in 2021, with repayments now representing 11.3 percent of government revenue in the poorest countries, up from 5.1 percent in 2010 (Figure 2). In most developing countries, the cost of servicing external debt now exceeds expenditures on health, education, and social protection combined (UNICEF, 2021).