Into the Unknown Heart of America

Since cavemen sat around a fire, the primary entertainment of mankind has always been storytelling. As any English teacher can tell you, there are only two basic stories: a) Hero goes on a journey, and b) Stranger comes to town. The former is usually the favorite, and for good reason.

Of all the stories ever told, my personal favorites are almost always adventure stories. I'm not talking about fiction.

For instance, the story about Sir Ernest Schackleton and his famous Endurance Expedition in 1915 had to be the greatest "man against nature" stories of the past century.

"Men Wanted: For hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success."

-Schackleton's newspaper advertisement, looking for volunteers

But I like looking back even further into history to find Larger Than Life characters. For instance, most people are aware of Ferdinand Magellan's 1519-1522 adventure when one of the original five ships sailed around the world. But what most people aren't aware of is just how great the odds were stacked against Magellan.

For example, Magellan was forced to put down three different mutinies before he had even reached the Pacific (one reason why he was standing alone against a small tribal army while the rest of his men looked on). Another element against Magellan was that his ships were under constant danger of being attacked by the Portuguese once they reached the Spice Islands (one of the ships was destroyed by a Portuguese man-o-war).

What I consider to be the greatest adventure story of all time is hardly known in America, despite the fact that most of it occurred in the continental United States.

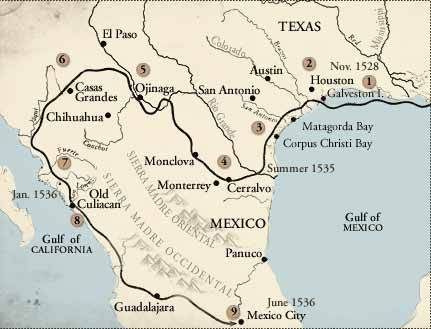

This adventure started on June 27, 1527, and didn't end (if you could call it that) until eight years later. The name of the man who led this adventure was Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, and his adventure was about more than survival against all odds. It was also about spiritual awakening, transformation, and the true nature of humanity. You can find the entire story here in de Vaca's own words written in 1536.

Please sit back, relax, and let me spin you a yarn.

[note: all images here are from the southwest writers collection]

The Tragic Narvaez Expedition

The story begins with conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez. Narvaez is historically famous for leading an army against Hernan Cortes in 1520, where he was defeated in open battle, wounded, and then imprisoned by Cortes for two years. (Cortes had actually left part of his army in Tenochtitlan with Moctezuma still imprisoned, in order to fight Narvaez's Spanish army at Veracruz.)

As governor of Cuba, Narvaez had oversaw the massacre of 2,500 indians who were bringing food to the Spaniards.

Pánfilo de Narváez

Narvaez was appointed governor of Florida in 1527 under the condition that he create two permanent settlements there. However, Narvaez, like Cortes before him, was only after one thing - gold.

Narvaez left Spain with 700 men, five ships, and the memory of the immense riches and fame Cortes managed a few years earlier. What he didn't know was that Florida had no gold and no empires to conquer. On April 14, 1528, the expedition touched land near present-day Tampa Bay with 300 men and 42 horses, after losing ships and men in a hurricane. de Vaca was the treasurer and sheriff of the expedition.

De Vaca already had a military background. He joined the military in 1511 and had already served in many bloody campaigns in Italy.

Narvaez almost immediately displayed poor leadership and ordered the ships to sail ahead to find a better port, splitting his ground forces in unknown lands. De Vaca and other disagreed with this plan, but Narvaez overruled them. The ships and ground forces never met up.

Since they completely underestimated the distances they were going to travel, the expedition soon ran out of food. They supplemented their supplies by stealing the crops of native Americans along the way. This, of course, didn't sit well with the starving indians.

The Spaniards soon found themselves under "constant guerrilla attacks", and eventually the local indians began "scorthed earth" tactics, leaving little for the europeans to steal.

Lost, desperate, sick with malaria, and losing hope, the expedition spent six weeks making rafts somewhere in northwest Florida. By September 22nd they had eaten all of their horses and had lost at least 50 men to sickness and indian attacks. On that day they pushed their five rafts into an unknown sea, each carrying 49 men.

For over a month the five rafts navigated the shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico, somehow managing to avoid the tropical storms that frequent the region that time of year. Lack of fresh water and hostile indians kept the expedition always on the brink of disaster.

That disaster happened once they reached the mouth of the Mississippi.

Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca

Strong currents and drifting in the night separated all the rafts. De Vaca could not keep up with Narvaez's raft, which pushed on towards shore.

At least one raft was lost with all hands during a tempest the following day. Five days later, with everyone on de Vaca's raft close to death, the currents pushed them towards land. After a wave overturned the raft, most of them managed to crawl ashore, their clothing lost in the sea.

It was November 6th, 1528, and they had just discovered (marooned on) Galveston Island.

They could see at their feet two of the dead men who had washed ashore. They could also see that the rest of us were not far from joining these two.

The Indians, understanding our full plight, sat down and lamented for half an hour so loudly they could have been heard a long way off. It was amazing to see these wild, untaught savages howling like brutes in compassion for us.

Compassion is not something the Spaniards had shared with the indians they encountered until this point. Now it was de Vaca and his comrades who required it.

the "Island of Doom"

De Vaca asked the indians to take them to their homes. The indians "were delighted" and literally carried them back to their village, where they had a dance celebration that lasted all night. In the morning they found the crew of another raft and sent four of the Christians ahead to look for Mexico.

Being in poor health and with the weather turning cold, they decided to stay there for the winter. Starvation set in, which led four of five men in one hut to eat each other. The Indians were appalled at this cannibalism. To make things worse, disease broke out and killed half of the Indian villagers and 75 out of the remaining 90 Christians.

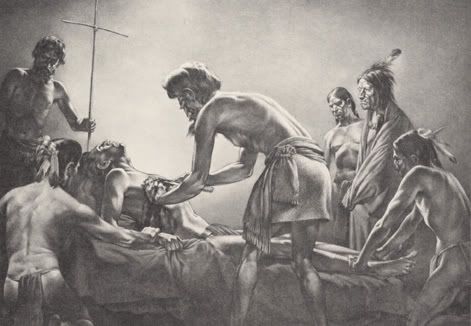

It was during this time that de Vaca learned to be an medicine man. He used a combination of local medicine man customs along with the more extreme Catholic customs of a country undergoing the throws of an Inquisition at the time.

In consequence, the Indians treated us kindly. They deprived themselves of food to give to us, and presented us skins and other tokens of gratitude.

The Wandering Merchant

De Vaca got extremely sick in the spring and was unable join a renewed effort to go south to Mexico. 14 Christians headed south without him, giving him up for dead.

De Vaca was vague on how he went from being a well-treated medicine man on Galveston Island, to being a slave on the mainland. Nevertheless, de Vaca and one other Christian remained a full year with the Capoques as slaves.

My life had become unbearable. In addition to much other work, I had to grub roots in the water or from underground in the canebrakes. My fingers got so raw that if a straw touched them they would bleed. The broken canes often slashed my flesh; I had to work amidst them without benefit of clothes.

He discovered that he had an advantage by being a white man. The indian tribes were usually hostile to one another, which prevented them from taking long journeys. He, being a neutral, could make the journeys for them. And that was his ticket to freedom - being a trader.

For six years de Vaca lived the life of a wandering merchant in 16th Century Texas. He became well-known and well-liked. His travels took him as far as Oklahoma and the Colorado River. He claims his only reason for not heading towards Mexico was his desire to take his lone, surviving Christian companion, Lope de Oviedo, with him. De Oviedo kept putting him off, telling him he would try next year.

Finally, in November 1532, he convinced Lope to leave and take his chances. After they had traveled several days they ran into a group of Indians who told them that they were holding three Christians as slaves. These were very cruel and hostile indians which terrified de Oviedo. De Oviedo abandoned de Vaca and headed back in the direction they had come, never to be heard from again.

De Vaca waited it out and eventually met up with Alonso del Castillo, the African-born slave Estevánico, and Andrés Dorantes, three of the explorers who had left de Vaca on Galveston Island six years ago when they thought he was fatally ill. All of the rest of their companions had died from cold, hunger, or being murdered by their cruel slave masters.

In order to arrange an escape for all four of them, de Vaca had to once again consign himself to being a slave for a period of six months until the time was right. During that time they told him the fate of their failed expedition.

The Story of What Had Happened to the Others

After leaving de Vaca on what they thought was his death-bad in April 1529, the 14 of them had stumbled upon the remains of another one of the original rafts they had built in Florida (no sign of the crew of this raft). They used this raft to cross several small rivers, although losing four companions along the way until they reached Matagorda Bay.

None of them being able to swim, they were discussing how to cross the waters when they were approached by several indians and one Christian, "whom they recognized as Figueroa [of Toledo], one of the four we had sent ahead from the Island of Doom [in 1528]."

Figueroa told them how his small group had also made it to Matagorda Bay when two of them and their Indian guide succumbed to cold and hunger. His other companion, Méndez, fled when approached by Indians, but he was chased down and put to death. While living with the Indians he was told about another Christian who was caught heading the other direction. He eventually met up with this Christian, who turned out to be Hernando de Esquivel, who had sailed on the Governor's raft.

Hernando told the ugly story of the fate of the Governor's crew. Somewhere south of Matagorda Bay Narváez, with two other crew, had abandoned the rest ashore and went south without them. They were never heard from again. Hernando and the rest of the men went south on foot, but one by one, cold, hunger and sickness claimed them. They turned to cannibalism. Eventually only Hernando remained alive. He was taken in by local Indians.

Hernando was taken away not long after telling Figueroa his tale, never to be seen again.

Figueroa, after telling the Dorantes party his tale, and two others later headed south, determined to either reach Mexico or die trying. The remainder of the Dorantes party were treated as badly as any slaves ever were. Three of the six were murdered for petty offenses. The rest suffered constant beatings and threats of death.

The Escape

Shortly before the four remaining Christians were to implement their escape, the tribal heads had a dispute and the tribes split up before the plan could be enacted. De Vaca was forced to spent another year as a slave with this brutal tribe before the tribes rejoined.

On September 8, 1534, de Vaca slipped away with an agreed upon time to meet his comrades. Once their journey started they came across another indian tribe, the Anagado, They told them of the fate of the last remaining raft.

another people, immediately ahead of us, called Camones, who came from close to the coast, had killed the men who landed in the barge of Peñalosa and Téllez. These men arrived so feeble that they could offer no resistance even while being slain, and the Camones slew them to a man. We were shown their clothes and arms and learned that the barge remained stranded where it landed. Now all five barges had been accounted for.

The Healer

The travelers soon came across a kinder indian tribe. It was here that de Vaca conducted his first successful "healing". It was to be their bread-and-butter through the wastelands of the Mexican desert.

A week later other indians came to the Christians to be healed. They prayed over them, breathed on them, laid on the hands, and for some reason their "patients" felt better afterwards. Word of this traveled swiftly, and soon other tribes were coming to them for their "medicine". Being in a safe and welcoming community, they decided to winter there.

During this winter, de Vaca was summoned to to heal a local chief. He arrived at the village only to find the chief had already died. De Vaca prayed over the chief and breathed on him before doing other "healings" in the village.

When they got back that evening, they brought the tidings that the "dead" man I had treated had got up whole and walked; he had eaten and spoken with these Sosulas, who further reported that all I had ministered to had recovered and were glad. Throughout the land the effect was a profound wonder and fear. People talked of nothing else, and wherever the fame of it reached, people set out to find us so we should cure them and bless their children.

[...]

With no exceptions, every patient told us he had been made well. Confidence in our ministrations as infallible extended to a belief that none could die while we remained among them.

Some months later de Vaca was summoned to heal a local indian who's chest was punctured with an arrow. Using a flint knife, de Vaca cut the arrow from the poor man's chest, thus performing the first recorded case of surgery in Texas history. The operation has earned him remembrance as the "patron saint" of the Texas Surgical Society.

Pushing On

Their journey continued upriver where they encountered many indian tribes of extreme poverty and want. The explorers wandered the desert naked like the local indians, eating little and asking for little. The indians, despite near famine, would share what little they had.

Despite traveling many leagues, the reputation of these healers preceded them.

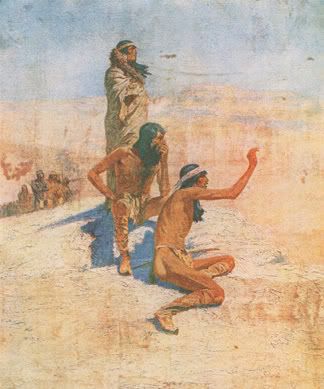

At sunset we reached a village of a hundred huts. All the people who lived in them were awaiting us at the village outskirts with terrific yelling and violent slapping of their hands against their thighs...

This people hysterically crowded upon us, everyone competing to touch us first; we were nearly killed in the crush. Without letting our feet touch ground, they carried us to the huts they had made for us. We took refuge in them and absolutely refused to be feasted that night. They themselves, however, sang and danced the whole night through.

It was at this point that de Vaca's exploration transformed into something entirely unexpected.

Leaving these Indians, we proceeded to the next village, where another novel custom commenced: Those who accompanied us plundered our hospitable new hosts and ransacked their huts, leaving nothing. We watched this with deep concern but were in no position to do anything about it; so for the present had to bear with it until such time as we might gain greater authority. Those who had lost their possessions, seeing our dejection, tried to console us. They said they were so honored to have us that their property was well bestowed--and that they would get repaid by others farther on, who were very rich.

All through the day's travel we had been badly hampered by the hordes of Indians following us. We could not have escaped if we had tried, they pursued so closely just to touch us.

I can't help but note the transformation here. Remember that eight years earlier these same Spaniards had landed in Florida intending to conquer the land by sword, take food of the Indians and any gold they might have, and kill any Indians that opposed them. They took hostages of the local Indians when it was useful. They saw no distinction between one Indian tribe from another, nor did they care.

And now look at them. They treat kindness with kindness. They are concerned about the well-being of the indians and honestly want to help them. They clearly see the distinctions between the tribes and understand their culture. What's more, one of the four is a black slave who is being treated as an equal.

But the transformation isn't complete yet.

De Vaca's escort multiplied to an extreme size.

When you consider that we were frequently accompanied by three or four thousand Indians and were obliged to sanctify the food and drink of each one, as well as grant permission for the many things they asked to do, you can appreciate our inconvenience.

And it wasn't just the indians from the previous village that traveled with them. Villages they were approaching would started sending out large parties to greet them and bring them back to festive celebrations.

Along the way de Vaca came across artifacts left over from what appeared to be the Anasazi civilization. The origin of these artifacts (such as copper rattles) was unknown by the local tribes.

After de Vaca's successful surgery, the treatment they received was practically religious.

The villages would offer them everything, even their homes. Their escort would dare not speak, or even look at them. When a village declined to escort them over a large desert, a sudden illness struck the region and killed several people. The natives became terrified that the explorers had caused this out of anger.

Because they were often traveling from one warring tribe to another, and because of the custom of the village offering everything to the explorers, which they then dispersed to their escorts from the previous village, de Vaca's group forced warring tribes to stop their fighting and work together.

Thus, as they traveled through the lands, they left peace in their wake.

After reaching the Pacific, they turned south. Shortly afterwards they began finding the traces of previous Christians in the area.

We hastened through a vast territory, which we found vacant, the inhabitants having fled to the mountains in fear of Christians. With heavy hearts we looked out over the lavishly watered, fertile, and beautiful land, now abandoned and burned and the people thin and weak, scattering or hiding in fright. Not having planted, they were reduced to eating roots and bark; and we shared their famine the whole way....They brought us blankets they had concealed from the other Christians and told us how the latter had come through razing the towns and carrying off half the men and all the women and boys; those who had escaped were wandering about as fugitives. We found the survivors too alarmed to stay anywhere very long, unable or unwilling to till, preferring death to a repetition of their recent horror.

Eventually they ran into a Spanish slave-hunting expedition that had been out-country for a many months. De Vaca summoned the indians of the area to bring food for their hungry countrymen.

We sent our heralds to call them, and presently there came 600 Indians with all the corn they possessed. They also brought whatever else they had; but we wished only a meal, so gave the rest to the Christians to divide among themselves.

After this we had a hot argument with them, for they meant to make slaves of the Indians in our train. We got so angry that we went off forgetting the many Turkish-shaped bows, the many pouches, and the five emerald arrowheads, etc., which we thus lost. And to think we had given these Christians a supply of cowbides and other things that our retainers had carried a long distance!

After this de Vaca's group attempted to pursued his escort to go home and plant their corn. This proved difficult.

But they did not want to do anything until they had first delivered us into the hands of other Indians, as custom bound them. They feared they would die if they returned without fulfilling this obligation whereas, with us, they said they feared neither Christians nor lances.

This sentiment roused our countrymen's jealousy. Alcaraz bade his interpreter tell the Indians that we were members of his race who had been long lost; that his group were the lords of the land who must be obeyed and served, while we were inconsequential. The Indians paid no attention to this. Conferring among themselves, they replied that the Christians lied: We had come from the sunrise, they from the sunset; we healed the sick, they killed the sound; we came naked and barefoot, they clothed, horsed, and lanced; we coveted nothing but gave whatever we were given, while they robbed whomever they found and bestowed nothing on anyone.To the last I could not convince the Indians that we were of the same people as the Christian slavers. Only with the greatest effort were we able to induce them to go back home. We ordered them to fear no more, reestablish their towns, and farm.

And so the transformation was complete. Cabeza de Vaca and his three comrades had transformed from conquistadors into spiritual leaders of the native tribes. The transformation was so complete that the Indians refused believe they were of the same race and creed.

The Spanish slave-raiders then led de Vaca's group away, and under arrest, to the local governor. They arrived in Mexico City on July 24, 1537.

Epilogue

Cabeza de Vaca had traveled 6,000 miles over the course of eight years. They were the first to see possum and buffalo. They visited tribes that wouldn't be visited again for decades to come.

De Vaca longed to return to Florida (a name for pretty much everything north of Mexico at the time), but it wasn't to be. Instead he was given a royal commission for the South American regions of the Rio de la Plata. He arrived there in 1540.

Instead of the year-long sea route via Buenos Aires, he chose to lead an expedition directly overland--1000 miles across unknown and supposedly impenetrable jungles, mountains, and cannibal villages. He accomplished this successfully, barefoot, from late November 1541 to late March 1542, from Santa Catalina Island via Iguazú Falls. The following summer he led an even more remarkable expedition about the same distance up the Paraguay in search of the legendary Golden City of Manoa.

However, this is life, and there is no "happily-ever-after" ending. You see, de Vaca had "gone native" in the eyes of his countrymen.

He had systematically prohibited enslaving, raping, and looting of the Indians--which were what the majority of the Spaniards had come for. So they deposed him....They returned him wretchedly to Spain in chains in 1543.

It took seven years before de Vaca was granted a trial, at which time the King annulled his sentence and cleared his name.

He died in honor in 1557.