I Am Alien

On the afternoon of September 21 a couple million humans shall storm Area 51, there to meet the alien. Or so they say. Initially, I thought I would be there now: mass public strangeness, that can be among the best, of the Stories. But eventually I realized that, like most everything in my life, it’s just not going to happen. But then decided—hey, that didn’t mean I couldn’t write about it. I mean, why not not go, but say I did? Inaugurate a new form of journalism: This Didn’t Happen; But It Might Have. So that’s, what this is. From time to time, until the day itself, September 21, I will inscribe here serial chapters of “I Am Alien,” the true-life non-fiction account of the quest for the alien. This, here, is the first.

We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. The car was electric; now, so were we. That we were electric meant we could approach silently, with stealth; this was right and meet, as we were steaming across these badlands to greet the alien. And it is best not to come up on the alien in great noise. The same is true of the United States military, bristling with weapons, growling and in grump, determined to prevent the people from reaching the alien. But we would not be stopped. For we were not the people: we were press. And it is well known, throughout the many galaxies, that the press may go, where the people may not. We knew the alien understood this. Whether the military would grasp it: we would see.

“Why is Barstow?” suddenly she asked.

Now that we were electric, there would be many such questions. Fortunately, for this question, I was prepared: I had done Research.

“They needed a place for the roads to have sex,” I explained. “Interstate 15, Interstate 40, State Route 58, Route 66, they all converge here, in a big dog pile. Among roads, Barstow is well known as a place to get jiggy wit it.”

“It’s too hot to have sex,” she decreed. There was wisdom in this: the temperature at the moment was 111 degrees; in Barstow, this is known as “a cooling trend.”

“Not if you’re a road,” I said. “Did you see the roads in the fire? The asphalt gave no shits. Even in places where there were the Dresden-style firestorms, the asphalt said: ‘You call this hot? Get serious. C’mon—bring it on!’”

We had both burned in the fire, were still burning, and so though deserts had not traditionally been the sort of place we would want to go, now, what did it matter? Also, it was required we ford the deserts. To reach the alien.

“But why ‘Barstow’?” she continued. It was her turn to not drive, and so she was free to ponder the Questions. Me, I needed to concentrate  on determining which of the various different roads, shimmering there in electrified view, was the “Real” one, and then endeavor to keep the car upon it. “What does ‘Barstow” even mean?”

on determining which of the various different roads, shimmering there in electrified view, was the “Real” one, and then endeavor to keep the car upon it. “What does ‘Barstow” even mean?”

I knew the answer to this one, too. “Originally the place was called Dead Man’s Throat,” I said. “But then in the 1940s it became a center of manufacturing of various sorts of bar equipment. Barstools, tables, chairs, corkscrews, coolers, the clubs the barkeeps keep behind the bar to whack people on the head when they become unruly—you name it. They would make all this stuff, then heap it in big warehouses, until it was shipped to watering holes across the land. Since in these warehouses they stowed the bar equipment, they called the town Bar-Stow.”

She thought about that for a bit. “You’re lying,” she concluded.

“I am fake news,” I confirmed.

We rode in silence for a while. Then she said: “This looks like the sort of town where Manson would be mayor.”

“I’m not sure Charlie ever got out here,” I said. “He was more a straight Death Valley kind of guy. Rick Steves was born here, though. The travel guy. That’s why every day he is frantically flying around to some other place on the globe: once you live in and then escape Barstow, you want to keep on the move, constantly, never rest, because if you stop, you might find yourself back in Barstow.”

“I read there are only two plants that grow here,” she offered. “One is called clod; the other is burrthistle. Clod is so called because it disguises itself by looking like a dirt clod. Burrthistle is unique in that it produces neither leaves, nor flowers: just burrs, and thistles.”

“Rick Steves talked about that on his NPR show,” I said. “The Barstowers cook these plants in a dish they call burrclod. They mash the plants together into big fetid balls and then bake them in a clay oven for six weeks. Then they take them out and glaze them with a flamethrower.”

“No,” she said flatly.

“Yes,“ I said. “That one is true. Also true is that Stan Ridgway, the Wall of Voodoo guy, was born here. Voodoo did the best version of ‘Ring Of Fire.’ Which Johnny Cash wrote, in a drunken bennies frenzy, about his wife’s vagina.”

“Why are you not locked up?”

“Speaking of names and wrongness,” I said, for I was fairly sure that we had, at some point, been talking about such, “why is your name Penelope? It has more syllables than it does letters. Pronouncing it induces tongue contusions. I need to conserve my tongue, in case the alien’s name is Axlthywkjlzomthyvw.”

“You think the alien is Polish?” she asked. “Maybe the alien is more Hawaiian. With a name like O’aauo’eaahao’eaoaoaeh.”

We had previously agreed that when Yahweh blasted the Tower of Babel, sending the people ululating into many languages, it was a shame the vowels and consonants were not more evenly distributed. Instead, you got Hawaiians, who had never heard of a consonant; Poles, to whom vowels are forever a mystery; and so on.

“Maybe someday Polish and Hawaiian will engage in sexual congress, and produce as offspring a language that is Sane,” I said.

“Maybe,” she said. “But they’re not going to do it in Barstow. It’s too hot.”

“No Pole has ever made it to Barstow,” I said. “They melt, long  before they get here. It’s worse than what’s going on in Greenland.”

before they get here. It’s worse than what’s going on in Greenland.”

“The alien will fix that.” She was convinced that once the alien could be made to come out, like Boo Radley, then it was inevitable that Bob Ewell would fall on his knife, at which time many things would change, and for the better.

“Do we have enough water?” at present her concern. “Because I don’t want to buy any in Barstow. This place, the water, seems like benzene would be the least of its problems.”

When you burn in a fire, and the water goes to benzene, you become all about clean, clear, pure, water. That is why we could not see out the rear-view mirror: because the back seat, it was crammed, from floor to rooftop, with cases of water. We’d initially thought of towing a double horse trailer, also jammed with water, but at the last moment the fire cleared momentarily, and we perceived, as through a glass darkly, that such might be excessive.

“Also,” she said, “I don’t have to be Penelope. I have lots of names. So: you can call me Al.”

“Why?” Now in my steady state: confusion. “Are we in a Paul Simon song?”

“No,” she said, “we’re in Barstow. If we were in a Paul Simon song, we’d be on the New Jersey Turnpike.”

“Pass me the first aid kit,” I urged. “I feel a need for Medicine.”

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=II8QrXHcPqc]

“I am not passing you the first aid kit,” she said. “You don’t need to be rummaging around in there, you’re driving; you should keep your eyes on the roads, so you can figure out which is the Real road, and which are the ones that are illusions of Medicine: we don’t want to be driving on those. Tell me what you want out of the kit, and I’ll hand it to you.”

“Vitamin V,” I said.

“No.” Again, this woman, in denial. “I am not giving you any Vitamin V. You’ll get too relaxed, and then you’ll start drifting onto the Medicine roads, which are really just sands. We’ll get stuck, and have to be rescued by Barstowers, who will want us to eat burrclod.”

We couldn’t have that. Al’s digestive system is sensitive; burrclod would for sure put her on a gurney.

“What we should have done is make this trip on horseback,” I suggested. “Then we wouldn’t have had to worry about any roads. The horses would find the way.”

“You’re too old to ride,” she said. “You’d get thrown, crippled bad, and then I’d have to shoot you, like Jane Fonda in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They. I don’t want to get in the jail, or the newspaper, for having to shoot you from getting thrown and crippled, while riding to meet the alien.”

“I’m not that old,” I abjured. “I might surprise you.”

“Maybe,” she said. “But not that much. Also, we’d never make it on horseback. We discussed this. At some  point we’d have to cross a road, and then we’d get hit by Carroll O'Connor in the toilet truck, like in Lonely Are The Brave.”

point we’d have to cross a road, and then we’d get hit by Carroll O'Connor in the toilet truck, like in Lonely Are The Brave.”

We both worshipped at the Church of Jack Burns, the protagonist of Lonely Are The Brave, also known as The Brave Cowboy, back when it was a book. Among Burns’ many godly attributes: he refused to carry a driver’s license, or any other form of identification, as he knew who he was, and didn’t need any papers saying so. So, we, too, Al and I, possessed no driver’s licenses. Also because we won’t stand in lines. And DMV lines are such that before you get to the counter, you will have grown a beard. Even if you are a woman.

“Are you going to give me the Vitamin V or not?” I asked.

“Not,” she said.

“It’s true what they say: there’s an opiod crisis,” I observed. “And the crisis is there are opiods in the first aid kit, and you won’t give them to me.”

“Here,” she said, “take this.”

I glanced quickly at what she was offering (it’s true the roads occupied most all my attention, and nearly all of my powers), and saw: a chocolate bar.

“What’s that supposed to do?” I groused.

“It’s supposed to go in your mouth, and fill it, so you’ll stop asking me to give you Vitamin V.”

As I sullenly munched the sugarfied variant of the sacred fruit of the cacao tree, I reflected that if Al were the alien, she would for sure give me Vitamin V. I had no doubt about that. Because we know the alien favors mind-altering substances, and pretty much at all times. We know this because, through all the many years, a truly mammoth percentage of those who report sighting the alien, had, at the time of sighting, some sort of liquor or narcotic, or both, then pulsing through their brainpans.

We were through Barstow now, which had to be counted as a blessing of some sort. But then I recalled there was a Sight back there, one maybe we should See. So once my mouth was again free, I embarked upon a new course of babble.

“Maybe we should take a look at the Old Woman Meteorite.”

“What’s that?”

“The largest meteorite ever found in the state of California, the second-largest in the US. It originally weighed 6070 pounds—almost as much as the president—but Lab Coats hacked off a big 943-pound chunk, for Study. It was found by some prospectors, in the Old Woman Mountains, a barren hellscape where not even clod or burrthistle will grow. The prospectors filed a claim on the land where was the meteorite, but the Smithsonian muscled in and said the meteorite actually belonged to them, and sent the Marines in, with a helicopter and cargo net, to hoist it off the mountain, and deliver it unto  their compound. The prospectors filed many lawsuits, but lost them all, as the courts determined the meteorite belonged to all the people. Now it’s in a museum, and people can go in and talk to the Old Woman, whenever they feel like it.”

their compound. The prospectors filed many lawsuits, but lost them all, as the courts determined the meteorite belonged to all the people. Now it’s in a museum, and people can go in and talk to the Old Woman, whenever they feel like it.”

“How much of this is just shit you’re making up?”

“None. All of it is true. True as you’re one of those bitter clingers Obama talked about, bitterly clinging to the Vitamin V that is lawfully half mine.”

“Feel free to file a claim; you will have no more luck than those prospectors. And we can’t see this meteorite, because it’s in the Smithsonian, which is in Washington DC, and not even you can get so lost as to end up in Washington DC, while driving from Butte County in California to Area 51 in Nevada.”

“But it isn’t in DC,” I said. “It’s in Barstow.”

“We’re through Barstow, though, and I’m not going back. I don’t like to turn around and go back on general principle, but especially when it involves going into something like Barstow.”

“But we might get some alien vibrations off it,” I persisted.

“I’m looking at it on my phone: it’s just a big ugly rock, that looks like it’s been attacked by a battering ram. And it’s in Barstow. Besides, we’ll get plenty of vibrations off the alien herself. We don’t need to settle for some faint rumblings from a rock that’s been contaminated by prospector, lawsuit, and Marine juju. We need to push on, get to Needles.”

“We’ll never make it to Needles.” I was suddenly sure of this. “We will be skeletal, long before we get to Needles. It’s 150 miles from Barstow to Needles, a literal road of bones, worse than the moon. Nothing, anywhere, the whole way, but dry grass, and cotton candy.”

“There isn’t even grass, and there certainly isn’t cotton candy. Are you seeing cotton candy?” She was concerned. “Tell me your brain is not bubbling with visions of cotton candy, out in the sands of Barstow?”

“It’s a true fact,” I insisted. “It’s even a poem. Here. I’ll recite it for you:

There was nothing between Barstow and Needles

But dry grass and cotton candy.

“Alias,” I said to him. “Alias,

Somebody there makes us want to drink the river

Somebody wants to thirst us.”

“Kid,” he said. “No river

Wants to trap men. There ain’t no malice in it. Try

To understand.”

We stood there by that little river and Alias took off his shirt

and I took off my shirt

I was never real. Alias was never real.

Or that big cotton tree or the ground.

Or the little river.

“Everything about that poem is wrong,” she said. “It has a river between Barstow and Needles, when there is no such river, and the people are taking off their shirts, which means they would receive from the sun third-degree burns before the poem ever finished, and also I don’t like that ‘I was never real’ bullshit, because I know I’m certainly real.”

“You may think so. But in Beyond Rangoon the guy says ‘We are but shadows. Briefly walking the earth, and soon gone.’”

“I don’t care what that guy says. And how many movies are we going to have in this story?”

“As many as will fit.”

“Just keep out the movies that say I’m not real.”

“That won’t do any good: there will still be the poems.”

“You just made up the poem; it’s the poem that’s not real.”

“No, it’s you who’s not real, just a figment, in a story, while the poem is totally real, it’s from Jack Spicer. But okay, I cheated a little, the first line isn’t actually ‘there was nothing between Barstow and Needles,’ but instead ‘there was nothing at the edge of the river,’ but I believe the poem should be recited whenever possible, so I fudged a little, to get it in here.”

“You need to not be driving now,” she said. “You’re having trouble with what is real, which means you are not going to keep us on the road that is real, which means we will drift of onto one of the non-real roads, and probably then blunder into one of the eleventy-billion meth-lab camps that are out in the desert between Barstow and Needles, and there we will be overrun by a swarm of meth monkeys, and then we really will be skeletal, so pull over; I’m gonna drive.”

I eased the car over to the shoulder, came to a stop. I couldn’t tell if the car was off or not. It was like Schrodinger’s car. Electric, it made no difference what you did with the thing, it still wouldn’t make any noise. Eerie. I’m not sure Henry Ford would approve. But then Henry Ford didn’t approve of Jews, either, so he could go fuck himself.

We sat there in the quiet. “Should we open the doors?” I asked.

“Does it look to you like anything out there is alive?”

I looked. No. There did not appear to be life, any life whatsoever, on this portion of the planet.

“Right,” she continued. “So if we open the doors, we won’t be alive either.”

So we switched seats by clambering over, under, around one another. It was comical. The sort of scene that, in my theory, explained why the alien had never, out open proud, contacted the humans. Always, the alien, has kept it deniable. Because the humans, as yet, are just too hopeless.

Al, she had a different theory. That the alien was, now, ready to show herself. She was only waiting, for this moment to arise. When once we reached The Area, and at the Appointed Time, the alien, she would be there. And then, henceforth, together, the alien and the human, they shall walk and talk, in gardens all misty wet with rain.

Though maybe not in Barstow. Or Needles.

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Be3OkvBZaIY]

It was better now that Al was driving. Let her worry about the road(s). Freed of the wheel, I could ease back and better ponder the pool of unsanity that was our mission. A pool that was long and wide and probably bottomless. And thus wanted a fair amount of pondering.

For instance, Al was proceeding down the highway at 10 mph. It was clear she believed she was motoring at a brisk and steady clip, but she had gone to the ganja, before she set off, and in that she had lost all sense of speed. These things happen; I had been here before. Once we were having a little powder party at the home of the Normal Couple—this was many years ago, and well before the man part of the Normal Couple suddenly went wild and started heaving the furniture through the huge front plate-glass window, thereby resigning from the ranks of the Normal—and at some point we ran out of cigarettes. It was the werewolf hour, not many tobacco-jones emporiums were open, and we were in the era before Lyft, which meant we had to drive. The woman part of the Normal Couple, when she merged on to Hwy. 99, grimly clutching the wheel, set off at a slug-like 10 mph. Cars whizzed by like we were standing still. Which we more or less were. I urged her on to greater speed, but she said she was driving so as to advertise confidently to any law-enforcement personnel that might be in the vicinity that she was not at all powdered up. I said she was advertising no such thing, that she was screaming with bells on that she belonged in a jail. I think eventually she “floored it,” and got it up to 30. That was maybe the longest stretch of highway in my life, and it was less than a mile. On the way back I did manage to convince her to take side streets, where her obdurate speedlessness would not be such an issue.

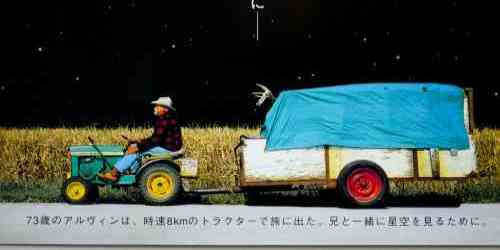

So now here I was again, years later, with another woman at the wheel enmeshed in non-ordinary Einsteinian time, cruising along a highway at 10 mph; this time, on the lifeless moonscape road(s) between Barstow and Needles. But I wasn’t particularly concerned. Al and I had built in sufficient time when planning our journey to account for the occasional calamity: this wasn’t even a calamity; it was just slow. I had no fear of law enforcement: if any gendarmes were to take an interest in this vehicle traveling slower than that guy on the lawnmower in The Straight Story, then long before we got to the part where they wanted to see the driver’s licenses, which we did not have, they would understand we were fire people, and so would back right off. I don’t know what it is, we must have some special sort of aura, maybe with flames shooting out or something, but whenever law jockeys encounter  fire people, unless the fire people are naked waving loaded firearms with white powders visibly streaming from their noseholes, the law jockeys tend to just turn and go on their way. The only problem would be if they would want us to roll down the window: Al maintained that it was not possible for life to survive outside the car, not on this part of the planet, and so if the window were to be rolled down, the outside would then come flooding into the car, and so we would go to the boneyard.

fire people, unless the fire people are naked waving loaded firearms with white powders visibly streaming from their noseholes, the law jockeys tend to just turn and go on their way. The only problem would be if they would want us to roll down the window: Al maintained that it was not possible for life to survive outside the car, not on this part of the planet, and so if the window were to be rolled down, the outside would then come flooding into the car, and so we would go to the boneyard.

But then I saw she was wrong about that, about the impossibility of life hereabouts, because, idly gazing out the window into the white hot desert, I saw, streaking impossibly thin sunblasted brown and thoroughly unsane, a meth monkey. I knew at once, that it had to be a meth monkey. Because who the fuck else would be running around out there? And, in our Research, Al and I had learned that this stretch between Barstow and Needles, it is basically one big long crime scene. Since nothing Sane or Decent can out there long survive, it is infested with meth monkeys, and other assorted mutants, pursuing lives of poaching, artifact vandalism, vehicle theft, chopshopping, racketeering, wanton rapine, and the occasional murder—though more often the place is used for after-the-fact body-dumping. Hazardous wastes are also strewn liberally all along this stretch. Which is why some parts glow in the dark. They even still rob trains out here. To wit:

The slow-moving trains with their potentially lucrative hauls provide easy pickings for the interlopers. The thieves, mostly homeless, down-and-out types hired by gangs who had stowed away earlier in the day at the Yermo yards, lie in wait for hours inside car ‘tubs’ until the train begins the steep ascent up the 18-mile-long Cima Grade. They infiltrate and ‘liberate’ the contents of the boxcars using hacksaws, bolt cutters, and other tools of the trade. At pre-arranged geographical points, the bandits toss out the goods where their accomplices wait in rented moving trucks ready to load up the booty—expensive electronics, Nikes, cigarettes, booze, or, if they are particularly unlucky, a boxcar filled with teddy bears.

Since the creature sprinting across the desert was not clutching a teddy bear, I assumed him to be a meth monkey. Then he leaped high into the air, and was gone. Presumably he had found a sand-yeti wallow, and had gone to ground in it, so he could no longer be seen from the road.

“Did you see that meth monkey?” I asked Al.

That was a mistake. For Al immediately went to Defcon One.

“Meth monkeys?” she exploded. “Meth monkeys are after the car? We need to get the rifle! Crawl back there and bring it up. Hurry!”

“I can’t, Al. The back seat is completely bunged up with all these water bottles. Only dynamite can plow a hole through to the rifle in the hatch. Do you want to set off dynamite in here?”

Al had pulled to a stop. “I don’t know what I was thinking—I should have brought the rifle up here when we stopped back there. This stretch is crawling with meth monkeys!”

I eschew firearms myself, but Al has an Annie Oakley component, and so had insisted on bringing along on the sojourn to the alien various implements that go boom. When I’d asked why, she’d said, “to protect the alien.” Apparently now a weapon was also needed against the meth monkeys.

“You’ll have to get out,” she said. “You’ll have to retrieve the rifle directly from the hatch.”

“But you said if we went out there, we would die.”

“I know. But it can’t be helped. You will have to sacrifice yourself, for the mission.”

“What do I care about the mission, if I have to sacrifice myself for it, and before it barely gets started?”

“What kind of attitude is that?” she said fiercely. “It’s people like you who are the reason America is not great again.”

“Are you crazy?” I laughed. “There isn’t even any America! You yourself said that’s what the alien will say, once she comes out.”

“I know,” she said, resting her forehead on the wheel. “I’m not thinking straight. It’s all this not driving. I’m suffering from motionless sickness.”

“Then get back to driving,’ I said. “Forget about the meth monkeys. And this time, try to drive faster than ten miles per hour. No meth monkey can get to the car if it’s actually moving.”

“I wasn’t driving any ten miles an hour!”

“Yes, you were. I’m sure you thought you were in the lead at Le Mans, but actually you were crawling slower than two snails.”

“You’re on drugs,” she said, disgusted.

“So are you, Al. That’s why you were driving slower than grandpa shuffling along in his walker.”

“As soon as I get the rifle I’ll bust you across the knees and then we’ll see who needs a walker.”

But then our argument was interrupted by  the dim sight and thin sound of an aged biplane, knifing through the white of the sky low to the southwest. We stared at it in wonder. Then I whispered: “I know who that is.”

the dim sight and thin sound of an aged biplane, knifing through the white of the sky low to the southwest. We stared at it in wonder. Then I whispered: “I know who that is.”

“Yes,” Al said. “It’s The English Patient.”

Of course. It had to be. The English Patient. The patron saint of the burned. And also avatar of the true reality: that on this sphere there are no borders, no boundaries, no nations, all are but creatures upon the planet, alone and together, and there are no aliens, anywhere, to anywhere, and this includes even farflung interstellar beings checking in from MACS0647-JD, complete with three ears, and no heads. The English Patient’s appearance, here, now, meant that Al and I, we were something more than Abbott and Costello, doing it wrong. We were on the right road.

(to be continued)

Comments

Thanks hecate, a masterpiece. Thank you especially for the

long awaited explanation of the seemingly inexplicable peregrinations of Rick the Steves. I had to immediately go explain same to my wife who, just as immediately, said yes, yes indeed, that is more than reason enough. We have been through Barstow a great many times and even twice stayed there, once in an encampment of sorts in the immediate environs, dining at a long lost truck stop, and once in someplace that advertised itself as a motel, dining in our room on comestibles procured in some bizarre stop-and-rob.

That, in its essence, is fascism--ownership of government by an individual, by a group, or by any other controlling private power. -- Franklin D. Roosevelt --

the

man just will not stop. There was no reason for it. Till came clear the Barstow. Here he discusses his Norwegian jones.

jeezum crow;

i've only had time to read half of this electric saga, and i hope it's not amiss to say that it reads like an amalgamation of jack kerouac, tom wolfe, ed abby, and hunter thompson, william t. vollmann, and richard brautigan. A+! thank you.

the

first line was brazenly stolen from Mr. Thompson. Then it galloped on from there.

well, imitation as the best flattery,

and all that jazz. i'm guessing that the second half will be as holy cockle shells electrifying as the first wild ride...er...gallop.

best creative writing i've read in a long time; thank you.