Hellraisers Journal: Edith Wyatt on "The Chicago Clothing Strike" in Harper's Weekly, Illustrated

Put on your fighting clothes.

-Mother Jones

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Wednesday December 15, 1915

From Harper's Weekly: Edith Wyatt on the Chicago Clothing Strike & Special Police Guards

In the December 11th edition of Harper's, Edith Wyatt offers the following account of the Chicago Garment Workers Strike, now ongoing in that city, along with news regarding police brutality, and some history on the practice of arbitration in the needle-work trades:

The Chicago Clothing Strike

by EDITH WYATT"THE story of civilization,” says Norman Angell in Arms and Industry, “is the story of development of ideas.”

One of the most interesting chapters of that chronicle is the narrative of the development of the idea of industrial arbitration in this country, in opposition to the idea of industrial war. Chicago is now watching intently a bitter contest between these two principles in one of her greatest industries, her trade in men’s clothing, a business truly enormous, the value of its product in this city being rated in the last census at over eighty five million dollars.

The largest establishment engaged in this trade in Chicago, and also in the world, the house of Hart Schaffner & Marx, has carried on its production for the last five years through the employment of the members of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. According to its agreement with the union, this house operates on a wage-scale differentially determined by trade board agreement; and settles its industrial disputes by the same trade board's arbitration. The board is composed of five members representing the firm, five representing the workers, and a neutral member whose salary is paid by each side in equal division, and who may give the casting vote in a tie.

Six weeks ago the employees of many other clothing factories in Chicago, hoping to obtain the same terms as those in vogue at Hart Schaffner & Marx, organized as members of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, and sent, through their president, Mr. Sidney Hillman, a letter to about two hundred individual employers, requesting these gentlemen to meet their officers for the purpose of arbitrating difficulties which had arisen in the trade. This communication received no reply from the majority of the recipients, except that several of the employers addressed stated in press interviews (which they have never contradicted) that they had thrown the letter into the waste-paper basket.

These employers obtained for their houses the special privilege of a police guard of over four hundred officers, nearly a tenth of the entire force. By the first of November this guard, according to a careful estimate made by the editor of the Christian Socialist—an estimate obtained from the Police Department Budget on record in the Municipal Library—had cost the citizens of Chicago sixty thousand dollars in police salaries on behalf of private interests.

As a justification for this extensive guard for private interests, Acting Chief of Police Herman Schuettler published in the Chicago Tribune on October 30th a list of 493 cases of violence in the present clothing strike. The list constituted a record of the most cowardly and brutal attacks on strike-breakers,—three persons against one, the beating of girls, the throwing of acid. Unfortunately, the report mentioned no violences as perpetrated against strikers, although many of the names and addresses on the list of sufferers from violence were known to be those of strikers. The report did not mention the notorious ease of a private detective employed by the owners who had struck a peaceable member of the union, had been arrested through the interest of Miss Ellen Gates Starr of Hull House, and has since been convicted and fined in the police court. Most serious of all, the report did not mention the terrible and widely known murder of a deaf-mute, a union picket, Samuel Kapper. On the 26th of October, as Kapper was standing quietly on the sidewalk four blocks away from the nearest garment factory, he was shot down in the open street.

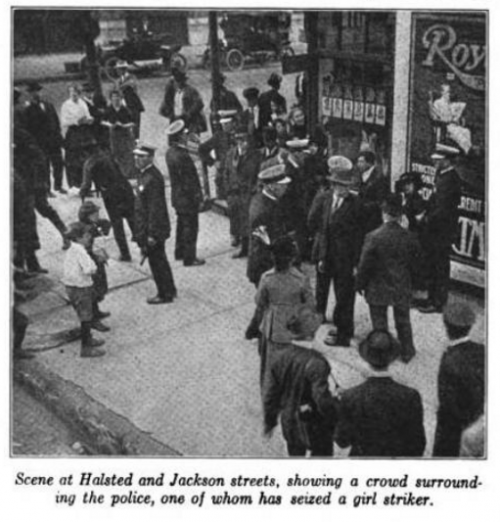

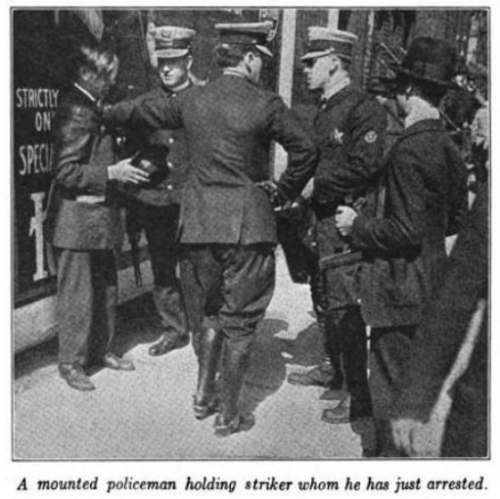

This omission, the tone of the list, and other circumstances have exposed the police to the charge of partisanship in their conduct in regard to the strike. They have not only failed to arrest persons illegally attacking strikers, but they have arrested strikers and social workers for the exercise of their legal rights of peaceful picketing, in appearing near the garment factories and stating the case of the union to strike-breakers.

On November 10th one thousand persons, most of whom had been arrested simply for walking on the pavements near the garment factories, marched to the City Hall together to appear in court. But the crowd was too large,—even the horde of accompanying police was too large,—to be confined in a court room. So every one was released, to appear on his or her own recognizance the following week. It is impossible to regard this performance in civil procedure as anything other than an absurdity.

In making arrests and bringing prosecutions against such persons among the strikers as have violently attacked their opponents, the police should of course receive the moral support of all admirers of good government. But enormous numbers of the arrests made by the police have not been of this character; and the methods of arrest have in many cases been absolutely unworthy of respect or tolerance. Here is an affidavit of one such case, which was obtained by the Director of the Immigrants’ Protective League, Miss Grace Abbott:

Bessie Att of the City of Chicago, County of Cook and State of Illinois, being duly sworn, doth depose and say that she is twenty-two years of age and resides at 1430 W. 13th street, and that previous to September 27th she was employed at Lamm & Co.’s as a canvas—baster, earning on the average $4 a week.

Deponent further states that on October 1st, at 5 p. m., she was walking, in company with Annie Weinstein, in front of Lamm & Co.’s on Jackson near Green street, when a policeman took hold of her arm and dragged her to the corner of the street where four officers were beating two boys, Josef Goodman and Charles Goldman, who appeared to be about fifteen years old. Blood was flowing from Josef’s nose and mouth, so deponent tried to help him, when the officer who had hold of her arm struck her a severe blow in the stomach, resulting in an incomplete fracture of the lower end of the breast bone. She fell against the building, was thrown into a patrol wagon, together with two young boys and a number of strikers, most of them girls who had also been injured.

Deponent further states that she is suffering constant pain.

This affidavit is also supported by a doctor’s statement of this woman’s injury.

Here is another such record:

Mrs. Josie Mott of the City of Chicago, County of Cook and State of Illinois, being duly sworn, doth depose and say that she is 35 years old, resides at 1428 Elk Grove avenue, that previous to the present strike she was a finisher at Kuh, Nathan & Fisher’s, earning $4 a week on the average.

Deponent further states that on September 29th, at 4 p. m., she and several girl strikers were picketing the Kuh, Nathan & Fischer shop on North avenue, and that she saw a fellow employee whom she knew very well looking out of the shop window; that deponent waved her handkerchief to the girl on the inside in friendly greeting, and that an officer who is regularly stationed there came up to her and took hold of her arms, gripping them so tightly as to cause great pain and black and blue marks, pulled her hair, struck her in the face and head, and kicked her about.

Affidavit after affidavit of offenses of this character was read by Miss Abbott early in October at a meeting of a neutral committee of organizations of women held at the Chicago Woman’s Club. These affidavits form a record not of civilized police regulation, but of degraded and needless police brutality. As a result of this revelation of the attitude of the police, the City Council requested the standing committee on police to investigate these matters, and requested the Mayor to appoint an aldermanic strike committee, to investigate the entire subject of the strike. The police committee, after an exhaustive investigation, has recommended the removal from the neighborhood of the factories of all sluggers and all non-uniformed police. The aldermanic strike committee has recommended the appointment of a permanent, neutral police committee for preserving order in the city on behalf of the representations of both sides in future industrial disputes. This appointment will have to be ratified by the entire council, and has not yet been voted on.

IN THE meantime ninety clothing firms, instead of throwing the communication of their employees into the waste-paper basket, answered it; arranged to hear the representations of the officers of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America; and are now operating, at considerable profit, plants which together employ between six and seven thousand workers.

On three points in the clothing trades situation and strikes in Chicago the general public has gained a misleading impression. The first of these points is the position of the two labor organizations frequently mentioned in this connection. The United Garment Workers and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers are two distinct labor organizations in Chicago, the last named having separated from the first because of internal differences. The United Garment Workers’ Union, which is the older association, has the charter of the American Federation of Labor. According to its constitution that body cannot issue a duplicate charter to the Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ Union, although this, in Chicago, is far larger numerically than the United Garment Workers’ Union.

Because of this technical difficulty persons opposed to both unions have asserted that a recognition of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ Union would mean an opposition to the American Federation of Labor. This is not true. The membership of the American Federation of Labor contributes to the support of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ Union, though for technical reasons it cannot give it a charter; and the officers of the Illinois Federation of Labor have appeared repeatedly in public in Chicago in the cause of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers.

The second element in the situation which the public does not understand is the psychological reason why numbers of the non-union employers have refused to meet representatives of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ Union. Prior to 1905 the clothing trades of Chicago were thoroughly organized in the body of the United Garment Workers. Numbers of the houses standing out against all dealings with unions were union houses ten years ago. At this time the United Garment Workers’ Union in Chicago is said to have abused its power by corrupt practices of the gravest character. A quoted instance of one of the least of its offenses is its unscrupulousness in dictating employment. It is said that there were two union garment factories in the city which were familiarly referred to throughout the business as “the Orphanage” and “the Washingtonian Home,” because these establishments were forced by the practices of the United Garment Workers’ Union to engage the most incompetent workers in the trade.

The bitterness preceding the strike of 1905, which resulted in a defeat of the United Garment Workers’ Union, still affects many members of the Employers’ Association. Their experience of a decade ago should be mentioned in a fair consideration of the situation, and may serve to explain, though it cannot justify, their prejudice against labor unions. Especially this experience cannot justify a prejudice against the Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ Union, which represents a secession from the United Garment Workers and has a record of five years’ reliable dealing.

The other element in the situation which the public does not realize is the peculiar necessity in the great needle trades of a just system of determining labor prices. Every woman who has ever sewed, either by machine or hand, knows how unexpectedly long it some times takes to complete some special operation in sewing, and that, on the other hand, it is sometimes possible to complete an operation more rapidly than one could have foreseen. Nothing except actual experience can estimate the amount of time and labor required for every new undertaking in clothing manufacture, and there are new undertakings with every change in style, and the clothing workers are paid by the piece through out the Chicago market. How is a payment to be determined fairly for each sewer and cutter and baster and buttonholer and presser in each operation of this changing and complicated craft? Only by clear, specific observation and agreement on the basis of known fact.

The difference in effort occasioned by difference in material is very great, and not to be determined by speculation, nor by a guess at what one might think reasonable. As between a presser who is paid fifty cents for pressing a certain kind of‘ coat and another presser who is paid sixteen cents for pressing another kind of coat, the fifty-cent presser, because of the greater difficulty in handling the material he must use, may be an underpaid worker, and the sixteen-cent presser may be a very well-paid worker, easily able, with a more pliable stuff, to complete so many garments in a week’s work as to earn from seven to eight dollars more than the fifty-cent presser.

ABOUT four years ago a union garment factory operating under a trade board found that the buttonholes the house had been making were too heavy, and that they puckered the material in a newer and lighter weight of clothing the firm was beginning to manufacture. On this account the firm supplied the buttonhole makers with a thinner cord of gimp for filling the edge of the buttonhole, and a finer grade of twist for working it. The difference both in the gimp and the twist was very slight. Naturally neither the firm nor the buttonhole makers had thought much about the matter at first. Some of the buttonhole makers could work more rapidly with the newer materials and preferred to use them. But the majority of the buttonhole makers claimed that the finer gimp and twist required so much more work for a buttonhole that they caused a decrease in wage. This decrease, they argued, ought to be compensated for by an eighth or a quarter of a cent increase in the rate for each buttonhole, according to the difficulty encountered in different grades of cloth.

They reported their difficulties to the trade board, which looked into the matter carefully. The firm’s representatives reported that in the course of a year the firm would be required to pay, in buttonhole makers’ wages, ten thousand dollars more than heretofore. The representatives of the buttonhole workers reported that the buttonhole makers, in working with the finer gimp and twist, would have earned for the same effort they expended formerly ten thousand dollars less than heretofore.

How was this matter adjusted? By a strike of the entire factory? By a silent submission on the part of the workers to a loss of ten thousand dollars? By a forfeiture on the part of the firm of ten thousand dollars in extra wages, with no corresponding receipt in output? By none of these unsatisfactory methods. By a special effort the firm obtained a kind of gimp and of twist which made a suitable buttonhole in light weight cloths, and yet could be used by the majority of the buttonhole workers as rapidly as the former heavier twist and gimp. The few buttonholers who could work rapidly with the buttonhole materials which had caused the difficulty continued to use these, and back-wages on the eighth of a cent and quarter of a cent basis were paid by the firm for all the buttonholes made with this lighter gimp and twist by the buttonholers whose work had been retarded by these materials. The decision of the trade board was satisfactory to every one concerned. In the non-union factories these complicated matters, the payment for each new style, material and process, are customarily determined by the hasty fiat of a foreman or a sub-foreman, from whom there is no appeal, and who has no time or opportunity to analyze operations and fix prices correctly.

THESE instances may serve to show the enormous possibilities of injustice in wage in the clothing industry, through unconsidered decisions. In the writer’s view this extremely simple but constant and every-day need of a just system of determining labor prices in the needle trades is the most important point in the entire situation. Think of the innumerable miles of stitching sewed every year by hand and machine for the wearers of ready-made clothing. Is all this work performed for the world to be paid for by undiscriminating judgments—on the old terms of arbitrary foremen and injustices for thousands of workers? Or is it to be paid for by the application of a clearer modern method to a multitudinous modern enterprise? Is Chicago’s history of civilization in one of her greatest industries in this terrible year of foreign warfare to be one of retrogression towards the ways of industrial war, or of progression towards the ways of industrial peace?

No one pretends that all the persons in the needle trades who arrange their affairs by arbitration and by a trade board’s rulings will live happily ever afterwards. But the establishment of this principle in the present situation would mean a genuine act of public spirit on the part of the employers involved, and a consummation greatly to be hoped for by all the persons who desire that this chapter of the tale of civilization in Chicago should have a happy ending.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE

Harper's Weekly

(New York, New York)

-Dec 11, 1915

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=GMc4AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

"Chicago Clothing Strike" by Edith Wyatt

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=GMc4AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

IMAGES

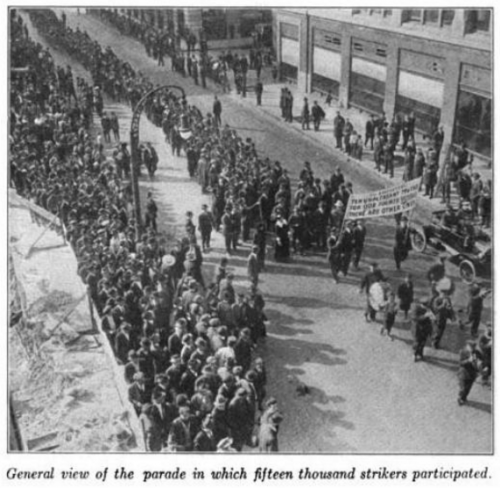

Chicago Garment Workers Strike of 1915, Harpers Wkly, Dec 11

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=GMc4AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

Chicago Garment Workers Strike of 1915, Police Seize Girl, Harpers Wkly, Dec 11

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=GMc4AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

Chicago Garment Workers Strike of 1915, Police hold striker, Harpers Wkly, Dec 11

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=GMc4AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, emblem

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=mJguAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

See also:

The Clothing Workers of Chicago, 1910-1922

The Chicago Joint Board, ACWA

Chicago, 1922

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=mJguAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

Chapter IV: Break from United Garment Workers in 1914

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=mJguAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

Chapter V: Strike of 1915

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=mJguAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

Making Both Ends Meet

The Income and Outlay of New York Working Girls

-by Sue Ainslie Clark and Edith Wyatt

(-with photographs by Lewis Hine)

Macmillan, NY, 1911

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=NskJAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

`````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````

Working Girl Blues - Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=12KarQjxKg4

Lyrics by Hazel Dickens

http://www.lyrics.net/lyric/5670398

My boss said a raise is due almost any day

But I wonder will my hair be all turned gray

Before he turns that dollar loose and I get my dues

And lose a little bit of these working girl blues