A Bright, Flashing Warning Sign

Imagine for a moment that some salesman offered you a deal.

They are willing to let you loan them money, and would only charge you a nominal fee plus a small rate of interest for the transaction.

In a sane world your answer would either be either, "Uh, no" or you would laugh in their face, depending on your mood at the time.

Pay to loan money?!? That's insane. Not just insane, illogical.

Would you believe that many professional investors are doing exactly that right now?

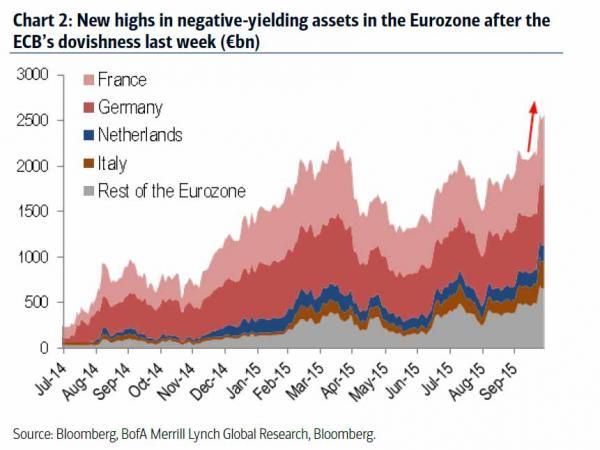

I'm not talking about just a few dollars, but $2.6 Trillion in Europe alone.

The Impossible

Let's be clear on something: negative interest rates are not supposed to happen. Period. The entire discussion of NIRP has been the domain of theoretical economics for generations.

The reason is obvious. Why loan money to someone at a negative interest rate when holding cash instead makes more sense?

The St Louis Federal Reserve said this just two years ago.

Conventional wisdom is that interest rates earned on investments are never less than zero because investors could alternatively hold currency.

It's more than conventional wisdom. There is an entire economic theory behind this called Zero Lower Bound.

Paul Krugman wrote, "the zero lower bound isn’t a theory, it’s a fact, and it’s a fact that we’ve been facing for five years now."

Zero Lower Bound is associated with the Keynesian economic problem of a Liquidity Trap.

And yet the impossible has happened in Europe and Japan, and even some negative mortgage rates to go along with deflation in Europe and Japan, and now the Fed is considering it as a policy.

Yesterday Italy sold $1.75 Billion worth of two-year bonds at a yield of -0.23%. Yes, people actually paid for the right to loan money to Italy, a well-known known serial defaulter.

What's more, more than half of Europe's 2 Year Notes trade not only below zero, but hit never before seen negative yields!

That's just bizarre.

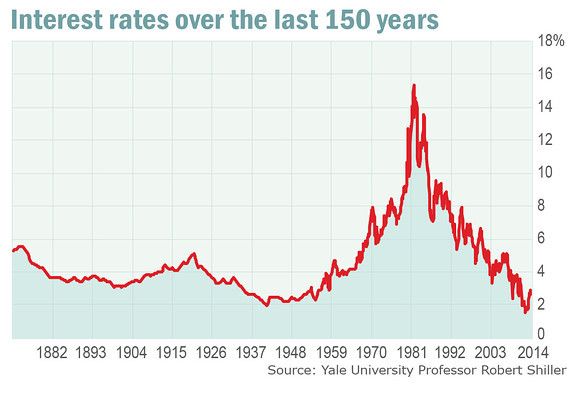

To understand just how bizarre this is you must consider historical interest rates and what they mean.

Even during the Great Depression, in midst of the worst deflation in America's history, interest rates never turned negative.

Why is it?

Consider the final sentence in that 2013 Federal Reserve report.

The existence of negative yields, however, provides no support for the argument that central banks should consider negative policy rates as a monetary policy tool.

Whenever something supposedly impossible happens the first question should be, "why is it happening?" Surprisingly few people are asking that question.

Whenever a Fed report says they shouldn't use something, and just two years later they are considering using it, it should set off some alarm bells.

The fact that so few are alarmed at a) something that shouldn't even be happening according to mainstream economic theory is happening, and b) the Fed going back on something they said they wouldn't do just two years ago, tells me that our financial leaders are like deer caught in headlights.

So why is it happening? I think there are several causes for this, including fears of global deflation.

Why deflation? Because it's only in a deflationary environment can you make positive real returns with negative yield bonds, and even then you would still do better with cash. Which means things would have to be bad for buying negative yield bonds to be only the second worst choice.

Meanwhile, artificially low interest rates encouraged massive borrowing without producing massive economic growth.

And so here we are, just 8 years later, with nearly $60 trillion in new debt piled on top of the prior mountain - while GDP grew by only $12 trillion over the same time period.

In other words, instead of saying to ourselves: Hmmm.... it was probably a terrible idea to pile up debt at 2x the rate of income growth, what the world did instead was to double down on that terrible idea and pile on more debt at 5x the rate (!) of nominal GDP growth.

Rapidly increasing debt in a stagnant economy means the economic surplus will get consumed by interest payments, even when interest rates are low. That translates into deflation.

Make no mistake, the next recession isn't going to destroy money. The next recession will only reveal where the money was already lost.

Most economists will point to bond supply and demand for this situation, and they are right.

However, they fail to point out that both the supply and demand are entirely artificial.

Let's start with the Liquidity Trap that Krugman has warned about.

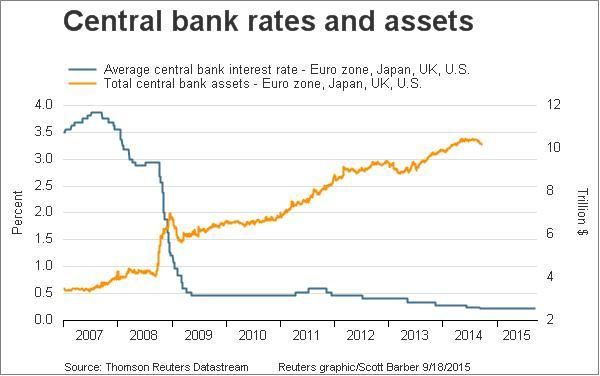

Delaying its first rate hike in nearly a decade after taking a pass in June and July means the U.S. central bank may have stepped further away from an escape from zero rates and $3.7 trillion of asset purchases bloating its balance sheet.

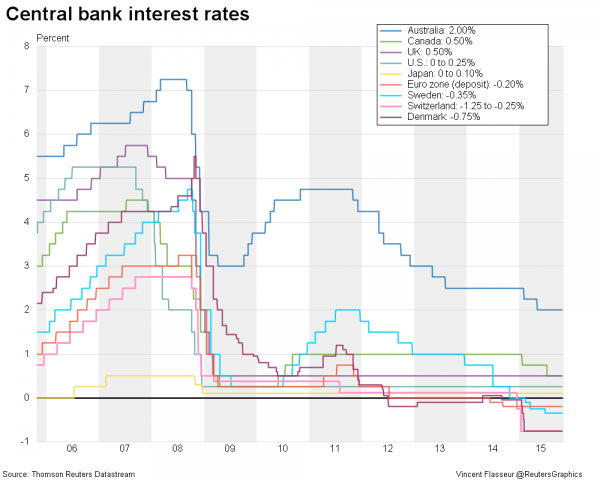

No central bank in post-War history has ever successfully made this escape. All four of the developed world’s biggest central banks — the Fed, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England — are in different stages of the same situation: near-zero rates and holding huge piles of financial assets.

The danger mentioned here is that Yellen won't be able to raise rates before the end of this business cycle, i.e. the next recession. This would mean that the Fed would be without any "ammo" to fight the recession, with the exception of extreme and unproven monetary policy.

But there is something else from the chart above that needs to be noted - the enormous pile of assets (mostly bonds) that the leading central banks have built up, and how that has pushed rates down to zero while pushing those financial asset prices up to nosebleed levels.

You simply can't create $10 Trillion dollars to buy financial assets and not create price distortions. For example, The Federal Reserve purchased 71% of all Treasuries for sale in 2013, and the Fed has no intention of trying to sell these assets anytime soon.

Such enormous demand for these bonds has created periodic liquidity problems, which translates into volatile price swings. For months now traders have been increasingly concerned with bond market liquidity.

they aren’t big buyers and sellers of corporate bonds anymore. This has made it harder for investors to trade large blocks of bonds-and it’s making them worried that they may have to take big losses if they need to sell assets in a hurry.

Pushing interest rates far below their natural levels has another side-effect. Through the entire history of modern banking, the credit markets have been the most trusted indicator of future economic activity.

For instance, abnormally low interest rates have traditionally been an indicator of the markets expecting a recession.

Since 2008 and this central bank monetary experimentation, people no longer look to the credit markets for guidance. Interest rates are now meaningless when it comes to predicting future economic growth.

It's important to remember that the world has never seen this before. It's completely unprecedented to have such activist central banks, and their policies have no historical comparison.

Simply put, we are off the map on a global scale.

There is no historical examples to draw lessons from. There aren't even established economic theories to use as guides.

We've left all of that behind.

What does it do?

Negative interest rates don't just turn the basic concepts of the bond market on its head, it also turns fundamental relationship between banks and depositors on its head.

American banks are actively discouraging customers from despositing money because banks lose money on the transaction. This can be seen most notably in Europe.

But the pressure for negative interest rates to drive cash out of bank deposits and into the economy is building. Switzerland, for instance, has negative central-policy rates that cost its banks $1 billion a year. Those costs haven't yet been passed down to consumers. But how much longer will banks eat that before adding fees and charges to Swiss accounts to defray the cost?

Negative rates are incompatible with modern finance, unless you completely change the rules all the way down to the consumer. The country closest to changing those rules is Sweden.

Sweden is the place where, if you use too much cash, banks call the police because they think you might be a terrorist or a criminal. Swedish banks have started removing cash ATMs from rural areas, annoying old people and farmers. Credit Suisse says the rule of thumb in Scandinavia is: "If you have to pay in cash, something is wrong."

...A resistance is forming, and some people are protesting the impending extinction of cash. Björn Eriksson, former head of Sweden's national police and now head of Säkerhetsbranschen, a lobbying group for the security industry, told The Local, "I've heard of people keeping cash in their microwaves because banks won't accept it."

Removing cash from the equation would remove the floor on how low interest rates could fall. It would also remove the only ability that small savers have to protect themselves from financial repression.

The real kicker is that negative interest rates have failed to do what they're promised to do.

The saving rates in countries with negative interest rates have actually gone up rather than forcing consumers to spend the money.

What's more, the monetary policy of QE has a poor record, both for failing to stimulate the economy, and for increasing wealth inequality.

Here There Be Dragons

Since 1981 the bond market has been in a secular bull market. There is almost no one on Wall Street old enough to remember a bond market that didn't go up almost every year.

No one on Wall Street would even know how to trade a secular bear market in bonds.

But now interest rates are scraping rock bottom. Bill Gross says that the bond market is approaching the end of a bull market "supercycle", and logic says that he's right.

Rates have to go up, short of dangerous monetary experimentation like banning cash, or disastrous global deflation.

Why does that matter? Derivatives.

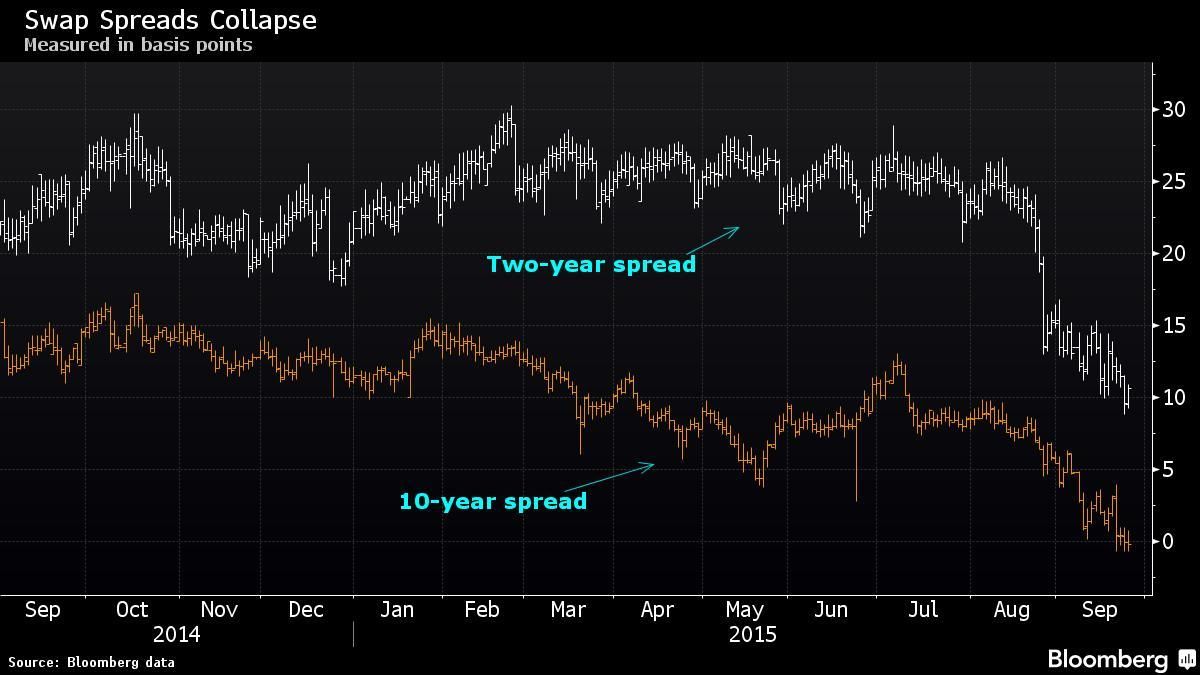

At the height of the financial crisis, the unprecedented decline in swap rates below Treasury yields was seen as an anomaly. The phenomenon is now widespread.

Swap rates are what companies, investors and traders pay to exchange fixed interest payments for floating ones. That rate falling below Treasury yields -- the spread between the two being negative -- is illogical in the eyes of most market observers, because it theoretically signals that traders view the credit of banks as superior to that of the U.S. government.

Insiders have called it “perverted”.

Swaps in this case aren't credit default swaps, but are instead interest rate swaps, which function like insurance against an unexpected rise in interest rates.

For three decades this has been a sure-fire winning bet for Wall Street.

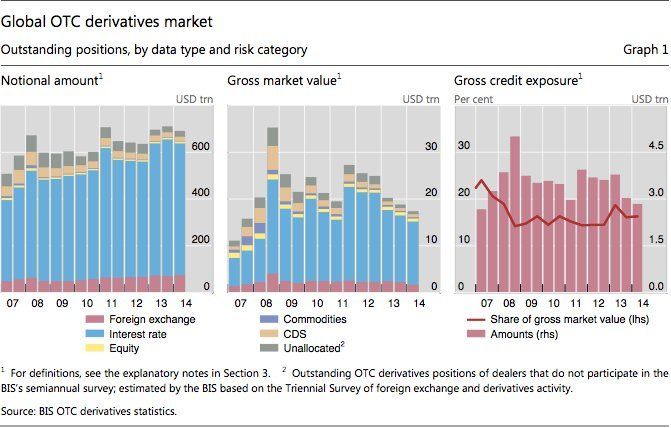

What most people don't realize is that the interest rate swap market is far larger than the credit default swap market that scared so many people in 2008.

The global notional market for interest rate swaps was about $560 Trillion last year.

While using notional values dramatically overstates the actual amount of money at risk (unless there are systemic defaults), even a small fraction of that mountain of money dwarfs the GDP's of the world.

What this means is that if interest rates were to rise, and rise quickly, it would trigger these interest rate swap contracts (i.e. someone would have to pay), and the money simply isn't there.

When interest rates rise, they rise across the board for an entire nation, and they may indeed help trigger interest-rate increases in other nations as well. Issuers have entered into trillions of dollars of contracts with Wall Street and other financial firms to cover their risk if interest rates increase. And if interest rates do increase substantially – they increase for the nation as a whole, in every state, for every borrower, and for every category.

So there is close to 100% correlation – the simultaneous losses being incurred could be likened to one firestorm spreading over the entire country.

And the reserves that were established to cover statistical assumptions of uncorrelated losses quickly disappear when it is correlated losses on a national basis that happen instead.

Wall Street and the banking industry remain as highly over-leveraged as ever. Just where are these hidden reserves of many trillions of dollars worth of capital to honor all of the derivatives contracts?

...

Do Wall Street and the other providers of interest-rate derivatives actually have the capital tucked away somewhere to cover the many trillions of dollars in increased interest payments for the entire nation (and the entire world), year after year, if rates were to rise by 5% or 10% or even more?

In practice, we know that Wall Street wasn't good for their promises on a little more than $1 trillion in subprime mortgage derivatives. There are more than 400 times as many interest-rate derivatives currently outstanding as there were subprime mortgage derivatives in 2008. There's no possible way. It would be an annihilation scenario, short of even greater levels of government interventions.

After carefully watching the financial markets for the last two decades, I've learned a few things about bubbles. I've learned that the best way to spot a bubble is when it no longer makes any sense at all.

When people started talking about the 'New Economy' during the Dot-Com Bubble, because making profits no longer mattered, then tech stocks no longer made sense.

When people with bad credit were going to get rich by flipping houses to other people with no credit during the housing bubble, then real estate no longer made sense.

Now central banks are going to pay for the privilege of loaning people free money, then banking no longer makes sense.

I want to be clear that I don't know where this road goes. No one does.

The only thing I am absolutely certain of is that we're rapidly running out of road, and the fact that our global financial leaders and politicians have nearly nothing to say on this matter tells me that they have no ideas.

Comments

Found another rare historical example

It seems the Swiss experimented with NIRP in the 1970's.

However, it wasn't even close to the same things we are seeing today.

First of all, there were no bonds with negative interest rates. The negative interest rates were only on bank deposits, and only on deposits from foreign nationals.

So actually it was more like capital controls than anything else.

Thus this was a whole different animal.

The why of NIRP

I've developed a couple thoughts I would like to float.

First of all, read this essay about NIRP: http://www.dailykos.com/story/2015/10/29/1441870/-A-Bright-Flashing-Warn...

I think that essay covers the "what", but I've left off the "why". Because I don't know the why.

However, I've come up with a couple ideas.

Idea #1) Why did the central banks do NIRP?

There's two things we know for sure: a) the world is saturated in debt, at levels never before seen, and b) the economy is growing very slowly all over the world.

It occurred to me that we might be reaching Peak Debt, and that's why the central banks are stuck on ZIRP and NIRP.

This thought came to me when I was watching a Michael Hudson video with him talking about how debt cancellation was a common thing in ancient days.

If this is the case then we are never going to see a strong economy again. At least not without a revolution first. And that any rise in interest rates will trigger cascading defaults.

Idea #2) Why does NIRP happen?

Negative interest rates don't make any sense at all if you look at it from one side.

But it occurred to me that traders look at it from the other side - price.

Nothing magical happens to the price when a bond yield goes from ZIRP to NIRP. It just goes up in a price a little.

What does happen is that it leaves its fundamentals behind. Sort of like the payments on a mortgage getting higher than its possible to rent the house for.

If you plan on sellng the bond anyway, then NIRP doesn't matter to you.

The problem is when the momentum stops. When the price of the bonds stop going up and start falling. Then fundamentals become important again.

And as we've seen when bubbles pop, the price will fall until the fundamentals support the price again. That means interest rates must increase several percentage points.

The problem here is the enormous mountain of interest rate swaps that can't be paid (see the essay).

If either of my ideas are true (or both of them), the the world's central banks are stuck. Any normalization of interest rates will crash the system. However, the current levels are unsustainable.

Feedback?

I've seen this dilemma described in several places now.

The central banks have painted themselves into a corner. Interest rates need to rise, but every financial institution now has a Wile E. Coyote style keg of dynamite on its balance sheet labelled "unregulated derivatives," a chain reaction waiting to happen.

Does finding the way out mean trying something drastic, like creating a different model entirely? One that abolishes, or at least sharply curbs the role of, Federal-Reserve type central banks?

Anyway, depending on who you listen to, the real economy is not reviving, appearances are only being maintained by rigging markets and manipulating statistics, the price of labor is in the cellar giving employers all the power and employees next to none, the so-called trade treaties will make a "race to the bottom" in all areas formally binding and permanent, and although the elites see a social explosion coming, their answer is total surveillance, domestic application of the counterinsurgency model, and militarized Israel-trained police.

More on NIRP

It isn't just me

Peak Debt?