the 1919 Red Summer race riots horrors

White children cheer outside an African-American residence that they have set on fire. © Getty Images

As I’d been reading and collecting links and quotes toward a post on ‘the Revolutionary possibilities of Civil Rights 2020’, two authors had mentioned ‘Red Summer’, as well as the bombing and burning of Black Wall Street in Greenwood, OK as historically analagous to 2020, or at least: past as prelude. And the following day, Up Jumped the Devil.

As Dickens seems to have borrowed heavily from ‘Red Summer’ at National Geographic, I’ll paste in a bit past Fair Use rules. To me it seems the depraved barbarity at play that summer needs a stand-alone diary. Fair warning: the final photo below the dotted lines may give you nightmares.

‘Lynching, stoning and burning: The 1919 ‘Red Summer’ race riots that America and Britain want you to forget but which echo today’, Andrew Dickens, June 28. 2020, RT.com

“Red Summer saw hundreds of people killed in a series of race riots across the US. Most deaths were white-on-black – including people being lynched, stoned to death and burned at the stake – but it was also the first time the black population had resisted the violence, both peacefully and with force. And, while such medieval savagery chills the blood and the levels of cruelty astound a 21st-century sensibility, there are parallels with 2020.

So, what fuelled it and why has it been brushed under the carpet of history?

The US at the time was a deeply racially divided country led by President Woodrow Wilson – a supporter of the Ku Klux Klan who was against black suffrage and actually resegregated elements of American society. White-led race riots and lynchings were commonplace – from 1889 to 1918, more than 3,000 were lynched, 2,472 of whom were black men and 50 black women. Black people, despite emancipation 57 years earlier, had far fewer rights than white people. But what lit the touchpaper for the bloodshed of 1919, and what made it so significant, was the return of soldiers from World War One. [snip]

White servicemen jumped on fabricated rumours of white women being assaulted by “Negro fiends” – rumours sensationalised by the press – and went on random sprees of assault and murder. The Washington Post, that famously “liberal” rag, even ran a front-page story organising white servicemen to gather at a certain location so they could attack black people in the city en masse. [snip]

Black soldiers returned to a different set of ire-inducing issues. Having risked their lives for their country, they came home to discover that their country and its president didn’t see them as complete human beings. At least 13 black veterans were lynched after the war. They weren’t war heroes; they were second-class citizens. But they were also motivated and emboldened.

A bloody rampage

“Red Summer” – a phrase referring to the bloodshed, coined by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s (NAACP) field secretary, James Weldon Johnson – was a series of violent events. The most serious of these began in April and ended in November. During that time, across dozens of American cities, white mobs, including women and children, rampaged, destroying black properties and churches, and murdering black people.

The Ku Klux Klan had a resurgence after decades of slumber, committing 64 lynchings in 1918 and 83 in 1919. In one of the deadliest events, more than 200 black Americans were massacred in Elaine, Arkansas, after black sharecroppers campaigned for better working conditions. [snip]

This meant that, in some cities, for the first time, black people fought back against the brutality, notably in Chicago and Washington, DC, where riots saw both black and white people killed (albeit still mostly black). In Chicago, 23 black people and 15 white people died after a black teenager, Eugene Williams, drifted on his raft into a whites-only section of Lake Michigan. He drowned when a white man, George Stauber, threw rocks at him, knocking him unconscious.

Mounted police round up African Americans and escort them to a safety zone during the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. © Getty Images

Dickens quotes J. Edgar Hoover as blaming the Washington riots on: ““numerous assaults committed by Negroes upon white women,” despite an absence of evidence, and the Elaine massacre on “agitation in a Negro lodge.” He also initiated an investigation of “Negro activities.”

He notes that sure, President Woodrow Wilson had ‘condemned the violence’ but did essentially nothing to stop it.

Given the fact that the returning black veterans defended themselves and their communities, they were dubbed ‘Bolsheviks’ and the papers of record in that time mirrored such, as this NYT headline: “Reds Try to Stir Negroes to Revolt.”

Dickens also quotes Geoff Ward, a professor of African and African American studies at Washington University in St Louis:

“That reign of racial terror, where again the exculpatory work of the white press, police, grand juries and others ensured that perpetrators were protected rather than punished, undoubtedly prolonged the period of American apartheid.”

The National Geographic piece also covers ‘Race Riots in Tulsa’ (Greenwood, noting kerosene bombs, not pitch), horror stories from Rosewood, FL in 1923, and more, plus photos galore. I had a pip of a time being permitted to read even with signing up for their newsletter, but you may fare better.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

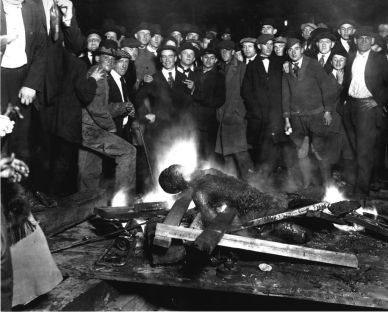

Will Brown, victim of Omaha, Nebraska lynching. The charred corpse of Will Brown after being killed, mutilated and burned. 28 September 1919

(cross-posted from Café Babylon)

Comments

A lot of this stuff ended up on postcards, I ended up with one

I don't know where it is right now but it's somewhere among all my belongings, but I haven't seen it in at least twenty-five years and many changes of address.

It's possibly buried in the overstuffed file cabinet but how I got it was from digging through my late Stepmother's paperwork looking for a property deed and seeing that postcard stopped me cold.

The setting was in a small town north of Dallas, the card was named 'the burning of Negro Smith' and it showed charred remains with a crowd of white people of all ages gathered around the charred corpse.Looking closely at the faces you'd think they were all at a carnival or something, some were smiling while a few looked like they wanted to be in the picture next to the corpse.

I asked my oldest Stepsister about the card and she said she'd forgotten all about that postcard but remember her mom saying something to the effect of "he did something wrong to a white woman" and that is all she could remember.

I hung onto the card, obviously, I'd heard about some these kind of events where a photograph became a postcard but I'd never seen one and talking about it with my University's American studies professor is where I learned that at one time, as far as he knew, there were a lot in circulation but not for long.

It's been many years since I even thought about that card but I can't forget the image when I have thought of it, and I can not only remember the image of the charred 'Negro Smith' but also a few of the faces of the crowd, particularly the one of a very young boy who was maybe as old as ten. What a future.

my stars, amigo.

i deeply appreciate your having shared those personal vignettes. i can't imagine which mind-images to choose, but i guess it would have to be about the leering young boy in the the crowd looking so intently at charred "Negro Smith". the thing is, we aren't born to hate, that's taught to us. remember all of the photos of little shavers dressed in Klan hoods and robes? they made me weep.

that you and your mother somehow survived Sonny is almost miraculous, but of course, the emotional scars linger.

this town and durango to the east both had Klan Klaverns. what did we do? introduce our adopted black/azteca son in this part of the world. oddly, though, one (allegedly) former klan neighbor did finally realize that J was just another kid, not some hated 'enemy'; or at least, so it seemed. walking back from town one day w/ J in a snuggly pack, 10-yr-old girl stopped me and asked why i was carrying that n*igger baby. i hope i'd even answered her remotely well...

bless your heart, and peace to you always, aliasalias.

do you recall whether

or not whether the postcard was new or used? i got to picturing if the later, did the sender write close to 'Having a marvelous time; wish you were here!' as so many send postcards with such brief messages are apt to convey.

It hadn't been used the back was blank

that was likely a relief,

wasn't it? thank you, and peace to you, my brother.