The latest craziness on Wall Street

Things always get nutty late in a credit cycle, when overconfidence reaches irrational levels. This time is no different.

But that doesn't mean that the craziness looks like the last time.

Here are some good examples of what to look for when the next crisis hits.

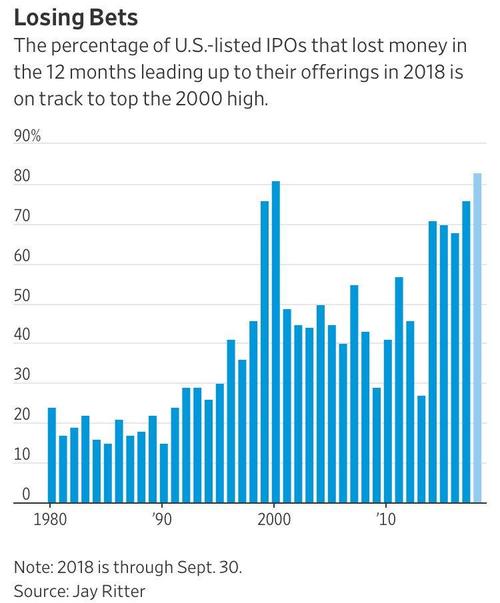

According to a new report by the Wall Street Journal, a record number, or 83% of US listed IPOs over the first three quarters of 2018, were companies that lost money in the 12 month prior to their going public.

According to the WSJ, this is the highest proportion on record dating back to 1980.Not only that, but investors who have been buying these money-losing companies have been rewarded. Stocks of companies that lose money and list in the United States this year are up an average of 36% from their IPO price. This actually outperformed the return for IPO stocks that are posting positive earnings, which came in at 32%. Both beat the S&P 500, which has returned 9% over the same course of time.

Consider Wall Street’s latest financial Frankenstein of a bad idea, collateralized fund obligations. Perhaps a better monster metaphor would be zombies, because these securities are the sort of terrible concoction that rise out of the Wall Street swamp and don’t seem to die. Collateralized fund obligations, or CFOs, were first given life in the early 2000s, but the market for them has mostly been dormant since the financial crisis. It has come back only recently.

...The biggest problem is that CFOs appear to transform equity investments into bonds, which are assumed to have much less risk than stocks. Structure and ordering of bonds can remove some of the extra risk and volatility that goes along with equities, but it can’t eliminate it. What it does is concentrate the risk somewhere until it breaks down the door of the closet bankers thought they had locked. That’s what happened with subprime loans during financial crisis.

That's all very interesting, but the real worrying concentration of risk on Wall Street lies in the corporate bond market.

Chief financial officers have been borrowing as much as they can get away with without their debt being classed as junk, because the move to junk leads to sharply higher borrowing costs. The attention paid to that rating boundary means the usual danger of leverage comes with an extra risk: the buildup of BBB bonds could mean even more downgrades to junk in the next recession than usual.

...The scale of the debt at risk of downgrade to junk is already frighteningly high, despite decent economic growth. Hans Lorenzen, a credit strategist at Citigroup, calculates that just the weakest BBB-rated bonds with a negative outlook or on review for downgrade, plus those where the issuer has other junk-rated bonds, amount to about half the existing size of the $1 trillion U.S. junk market.

More than $500 billion of these BBB-rated bonds are just one downgrade away from being junk, according to Fitch Ratings.

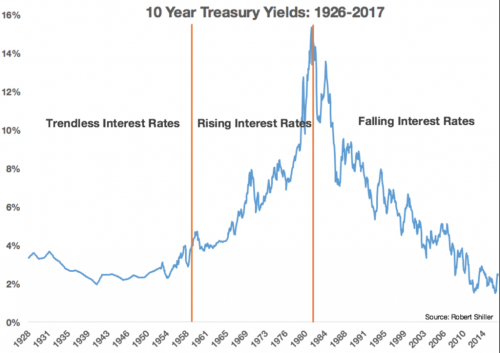

So why does this matter? Because a 37-year long bull market in bonds has come to an end.

Interest rates had fallen for 36 year.

Let's put that into perspective.

We’re currently living through the second longest bond bull market in recorded history, and the longest since the 16th century, according to a new research paper from the Bank of England.

...“The average length of bond bull markets stands at 25.8 years, and the range falls between 61 years (1451-1511) and 12 years (1718-1729). Our present real rate bond bull market, at 34 years, is already the second longest ever recorded,” Schmelzing writes.

Interest rates have fallen for so long that last year they reached their lowest levels in 5,000 years of recorded civilization.

When you have to go back to the ice age to find lower interest rates, you know that they can't fall much further.

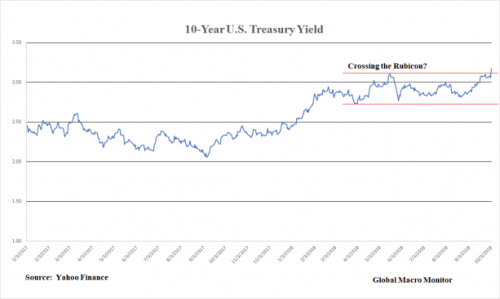

Sure enough, the markets are slowly coming to grips with this new global reality.

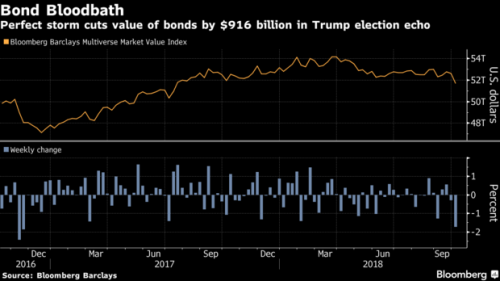

Global bonds are hitting fresh milestones of misery.Strong U.S. data, a tighter-than-expected monetary trajectory, rising commodity prices and brewing wage pressures are conspiring to push Treasury yields to cycle-highs, hitting money managers of all stripes.

The value of the Bloomberg Barclays Multiverse Index, which captures investment-grade and high-yield securities around the world, slumped by $916 billion last week, the most since the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election victory in November 2016.

American high-grade obligations are down 2.53 percent in 2018 -- a Bloomberg Barclays index tracking the debt has dropped in just three years since 1976.

“Bond investors have rarely seen losses like this over the past 40+ years,” Ben Carlson, director of institutional asset management at Ritholtz Wealth Management, wrote in a blog post. “Any further moves higher in rates could lead to the worst year since 1976 in terms of overall bond returns.”

There are no traders left on Wall Street that even know how to trade a bear market in bonds. I'd bet the algorithms don't know how either.

Comments

Remember that one guy from the 2008 crash...

...with a glass eye and Asperger's Syndrome, who was revealed as the literal "one-eyed king in the land of the blind" when he made out like a bandit betting against the market that no one else realized was about to "lay an egg"?

I wonder who the lucky winner will be this time...?

In the Land of the Blind, the One-Eyed Man is declared mentally ill for describing colors.

Yes Virginia, there is a Global Banking Conspiracy!

You mean the guy in "The Big Short"? A film worth watching

again. Notice in the closing credits where they pointed out that the banks were already back at again (2015).

chuck utzman

TULSI 2020

That first IPO chart is very strange.

(I’ll copy it below.)

So, what I see (and recall) is that an average 20 percent of IPOs for the last half off the 20th century were companies that did not yet turn a profit. The assumption is that the idea and potential and talent behind these companies was so strong that it was worth the risk to buy in low at the very beginning.

Then, at the turn of the millennia, 1999 and 2000, that 20 percent suddenly shot straight up to 80 percent unprofitable and held for two years, only. It was the dotcom boom and bust. Tech start-ups everywhere were swimming in money from VCs and investment bankers investing in little more than vaporware. Was it millennium madness?

For the next 14 years, which included the 2008 crash, the level of unprofitable IPOs averaged 40 percent. People were more willing to take risks on not-yet-profitable companies, and some of them did very well indeed, like Facebook and Google. It was a time of war, a time of innovations in tech and weapons, and a time of unbridled speculation in investment banking.

Then, in 2014, again there was a spike in the chart — unprofitable IPOs towered about 70 percent. But this time the risky speculation lasted five years! In 2018, the number of unprofitable IPOs is over 80 percent.

What I want to know, is what the hell happened in 2014? Besides toppling the Ukraine government and kicking off a semi-violent Cold War with Russia? Is it private bankers again with too much concentrated money and no place to put it? It’s very striking considering nearly a century of stats showing the opposite.

[EDIT] The other thing that happened in 2014 was OPEC crashed the oil markets. I believe that was supposed to wipe out Russia, but it made another fine mess.

Investment banks know they are too big to fail.

Anything goes, even the tepid Elizabeth warren commission was gutted.

I've seen lots of changes. What doesn't change is people. Same old hairless apes.

Well, these underwriters, like Goldman Sachs

...are letting a full 80 percent of companies going public to do show while in the red — unprofitable. No dividends. This is historically unprecedented, except for the year 2000, when it blew the markets and scooped all the inexperienced money off the table.

Alan Greenspan said that markets that become distorted are caused by this "irrational exuberance," when investors are so confident that the price of an asset will keep going up, they lose sight of its underlying value. They overlook deteriorating economic fundamentals in the pursuit of ever-higher returns. Toward the end of the cycle they even get into bidding wars, sending prices up even higher.

It would be nice to have smarter, non-ivy-league educated economists in charge with the intelligence to stop it when it becomes visible, like, oh... six years ago.