Lessons from a forgotten American Occupation

Afghan President Hamid Karzai said that the Afghan war was 'imposed' on the Afghan people and that he's not interested in having the Americans stay.

The best term I've seen is this one:

We lost the war, but won the battle.

It's the same story that an American could have written 80 years ago.

Augusto Cesar Sandino

America invaded Nicaragua in 1912 because its government owed American bankers money that it couldn't pay back.

American bankers collected Nicaraguan customs duties, paid creditors and disbursed the remainder to the government.

U.S. interest in Nicaragua included the protection of American investments in the area, the desire to maintain general calm in the larger Panama Canal neighborhood and a commitment to keep other nations from completing a competing transoceanic canal.

During this time the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty was created. With this treaty...

the United States was granted a 99-year lease on two Nicaraguan islands (Great Corn and Little Corn islands in the Gulf of Fonseca) as the sites of possible future naval bases. Of greater importance was the granting of a perpetual option to purchase the Nicaraguan canal site.

Given the internal troubles that preceeded our invasion, our occupation was largely peaceful and tolerated.

Things worked well enough that the Marines were withdrawn in 1925. That's when the real trouble started.

The competing forces in Nicaragua labeled themselves as Liberals and Conservatives. When the Marines withdrew the Conservatives launched a Coup and seized power. They took control of the national guard and used it against the Liberals. The Liberals took up arms and a civil war had begun. With the Liberals on the verge on retaking the capital, America forced a cease-fire on the combatants.

The Marines returned in 1926, this time in larger numbers. The Marines backed Aldolfo Diaz, the pro-American, conservative president. Back in America, there were concerns.

Democrats in Congress voiced opposition to the heavy-handed American actions and charged President Coolidge with conducting a "private war." Without a tinge of remorse, Coolidge responded by asserting that American lives and property needed to be protected and foreign meddlers had to be kept at bay.

Hmmm. Sounds a little familiar, doesn't it?

After about a year of this both sides managed to sit down and agree to the Treaty of Tipitata (May 11, 1927).

The conditions of the treaty were:

a) The warring factions in Nicaragua agreed to lay down their arms and abide by the results of a U.S.-supervised election scheduled for the following year;

b) the U.S. government also agreed to conduct training for a Nicaraguan national guard.

Later known as the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua. It was supposed to maintain order and replace the Marines as peacekeepers in that troubled nation.

The election was held and both sides agreed to the results. That is, both sides except for a relatively unknown figure named Augusto Nicolas Calderon Sandino.

Augusto Sandino is a legendary figure in Latin America. He's considered a national patriot on the order that George Washington is in America. His background is very humble.

he was born illegitimately to a peasant worker named Margarita Calderon and her married boss, Gregorio Sandino. However, when he was about ten years old his mother abandoned him and he went to live with his maternal grandmother. He was later brought into his father's household but he was forced to earn his keep by working and was never fully accepted.

In 1921, what might be interpreted as the climax of his life occurred when he shot, but did not kill, Dagoberto Rivas a son of an important Conservative in the village in retaliation to some comments which Dagoberto had made about his mother. He then ran away to the Pacific Coast of Nicaragua and from there to various other Central American countries. He finally landed in Mexico, however, and he spent the next four years working for Standard Oil. While there, he began to get involved in several diverse radical groups which seemingly influenced his perspective on life and hence his future actions.

Augusto returned to his homeland in 1926 as the Statute of Limitations on his crime ran out.

When the rebellion started in 1926 he took his meager savings and purchased weapons that he used to arm workers at a US-owned mine. His inexperience showed, but he learned from his mistakes. He gradually refined his warring techniques into a guerrilla hit and run style of fighting like the Vietnamese employed in the Vietnam War.

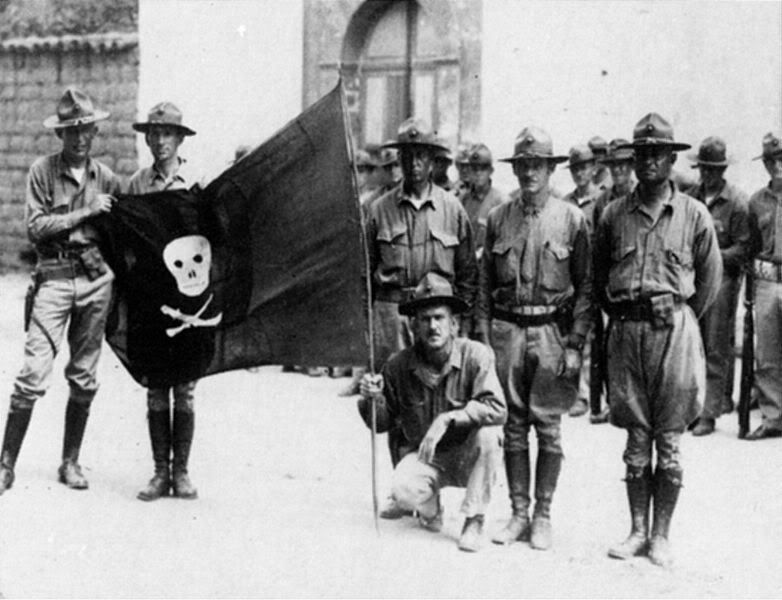

When the Treaty of Tipitata was signed, Sandino consider it a sell-out by the Liberal leadership because it left the Americans still in control of Nicaragua. He organized the Ejército Defensor de la Soberanía Nacional de Nicaragua (EDSNN-Army in Defense of the National Sovereignty of Nicaragua) and vowed to keep fighting until the Americans had left.

This decision changed the war for Sandino from a case of Nicaraguans against Nicaraguans to Nicaragua against the world.

Even though Sandino was an idealist with radical political and social ideas such as having communal lands and a unified Central America, Sandino was always a man of action and organized the sentiments of the common peasants into revolt. These common people provided the manpower to fight and die when needed as well as a constant information network for Sandino's backwoods fighting.

Sandino believed in the glorification of personal heritage and liberty and once said, "The sovereignty and liberty of a people are not to be discussed, but rather defended with weapons in hand."

"General Sandino, the bandit chief, is through."

- Marine General Feland, August 27, 1927

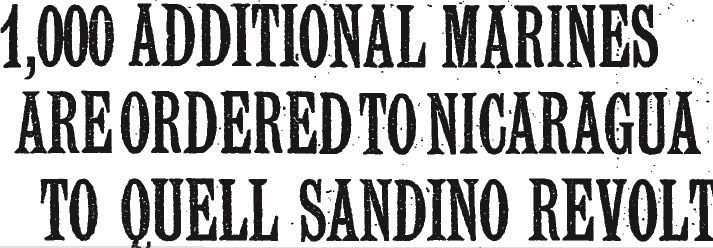

NY Times headlines, January 1928

The Americans responded to this peasant revolt in much the same way it responded to the revolt in the Phillipines just a few years earlier.

The United States Marines and the Guardia launched a counter insurgency war against the forces of Sandino. While he unquestionably organized a nationalist resistance force, U.S. policy makers defined Sandino and his soldiers as bandits. This decision helped define the military tactics that were to be used. Since the U.S. was not fighting a legitimate military foe, the rules of war (such as they were) did not apply. The Marines and Guardia made little distinctions between the Sandinistas and the civilian population: not only combatants but civilians were targets and subjected to the regular use of excessive force and torture.

[...]

Beatings by the Guardia and Marines were the most common form of torture. These included the use of fists and feet since a number of prisoners were also kicked or stomped. A form of water torture, which consisted of forcing water down a prisoner's throat until the prisoner choked, also occasionally occurred. Peasant women were raped. Psychological torture was also used since Nicaraguans were routinely threatened with beatings and executions, including decapitation. These were more than idle threats. Ironically (given the horrified outcries at the beheading of U.S. citizens in Iraq today), photos of Marines and Guardia soldiers displaying the severed heads of Sandinistas they had killed were published in Nicaragua and throughout Latin America.

Whoa! Deja Vu!

Sandino Revolt Believed Crushed

- NY Times headline, January 24, 1928

Violent Partisanship And Seething Politics Make True View Of Situation Hard To Get

- NY Times headline, March 4, 1928

After some initial mistakes, Sandino quickly mastered the art of guerrilla warfare. The rebels used the jungle to hide from American forces and were rarely seen outside of quick hit and run attacks. Sandino had to adopt these methods. His forces were largely armed with 19th-Century rifles and machetes.

A New York Times correspondent flew over the area in 1928 and described the terrain as "thickly wooded mountains . . . tortured into a patternless wilderness of peaks, ridges, and rock-strewn cliffs.... Its infrequent trails are almost invisible from the air."

Bernard Nalty, author of the U.S. Marine Corps historical study on the Nicaraguan campaign, points out that "Sandino's men were adept at camouflage. Seldom did they move in large groups, and, if at all possible, they marched at night." Sandino's troops learned the habit patterns of the Marine aerial reconnaissance flights and took advantage of them; when his forces moved at other times during the day, they used the jungles for concealment.

Sandino kept fighting a guerrilla war against the Marines until Hoover, in one of his last acts as president, withdrew the troops in 1933. Sandino's army was still active and undefeated.

Natives Say Nicaraguan Bandit Chief Is Admitting Defeat

- NY Times headline, March 28, 1928

Hmmm. Doesn't this NY Times article sound familiar? We can't withdraw for years. There would be anarchy if we left.

Do the same people write for the Times now that did in 1928?

Hoover's decision to withdraw was not made by choice. The Great Depression was forcing him to redeploy his increasingly meager budget. The War Hawks in the Republican Party also fought against the withdraw.

Supposedly, the military seized Sandino's papers where he planned a "campaign of extermination"(NY Times, August 19, 1931) after the Americans withdrew.

But instead of a campaign of extermination, Sandino emerged from the jungles early in 1933 and embraced peace. He agreed to disarm almost all of his troops and return to pre-war activities. Hardly the actions of a "bandit chief".

130 Marines were killed in action in Nicaragua.

But like most Latin American revolutionaries, Sandino's story does not have a happy ending.

With his ideal fulfilled, Sandino agreed to lay down his weapons and signed a preliminary agreement with the Sacasa government. The agreement was that, in exchange for peace, some men who wished to stay with Sandino could do so in a commune in the Rio Coco commune. These men would be formed into an auxiliary military group under the president's supervision for one year.

In 1934, with the review of his "auxiliaries" getting ever closer, Sandino told the President that he might not lay down his weapons because he believed that the National Guard was unconstitutional. Sacasa called Sandino to Managua to speak with him and when Sandino arrived he publicly announced that he thought that the National Guard was unconstitutional. Sandino's talks with the President resulted in an agreement which would, among other things, reduce Somoza's power through the National Guard significantly. On February 20, as Sandino returned from speaking with the President, the National Guardsmen under Somoza's command, fearing a loss of power, surrounded him and his party and executed them. The next day the National Guard raided the northern commune, destroyed it, and killed most of Sandino's men, their wives, and children.

As many of you are probably aware of, the Somoza family went on to be one of the most corrupt and brutal dictatorships in Latin American history. All the while fully supported by the United States.

In 1979 a rebel group threw the Somoza dictatorship out of the country. That rebel group was called the Sandanistas.

Comments

Sandinista!

It's up to you not to hear the call of I don't want to kill.....

I guess we're

doomed to repeating everything over and over and over again. Ugh.

dfarrah