Hellraisers Journal: Nils Hanson on the Organizing Drive of the AWO in the Mid-Western Wheat Fields

The red card is cherished as much and its objects understood as well

by a black man as by a white one.

-Solidarity, Fall 1915

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Tuesday December 21, 1915

From the International Socialist Review: Nils Hanson on Organizing in the Wheat Fields

In the latest edition of the Review, Nils Hanson discusses working conditions, living conditions, and the great organizing drive, launched by the Agricultural Workers Organization, this past fall in the harvest fields of the mid-western states. He tells of following the wheat harvest from Kansas on up to North Dakota.

The A. W. O. of the Industrial Workers of the World, has become such a menace that the North Dakota farmers claim they will import Negroes as harvest hands next year. In response to that threat, the I. W. W. newspaper, Solidarity, recently gave "John Farmer" this warning:

The I. W. W. has some good Negro organizers, just itching for a chance of this kind. Thirty thousand Negroes will come and 30,000 I. W. W.'s will go bak. The red card is cherished as much and its objects understood as well by a black man as by a white one.

From the International Socialist Review of December 1915:

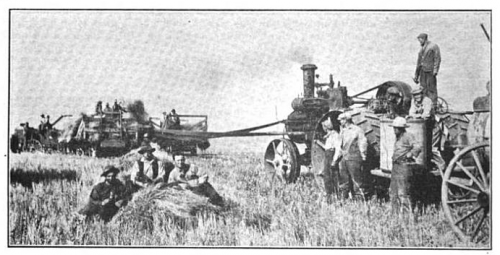

THRESHING WHEAT

By NILS H. HANSON"IT'S the guy with the rig that gets the dough," is a statement often I heard through the wheat country. The most of the men, the real threshers, those who make the bundles—the pretty bouquets-jump from the shock to the straw-stack and elevator—those men, some of them at least, knew that also. They knew that for every $3 or $3.50 they earn their boss makes from six to eight dollars on each and every one of them. Yes, while they make their daily wage he makes his daily pile of from one to two hundred and fifty dollars.

A big 42 to 44 cylinder separator can crush out from three to four thousand bushels in one day. The "thresher" gets from 10 to 14 cents a bushel for wheat, and from six to eight cents for oats and barley. This holds good in the Dakotas where they thresh from the shock. In Kansas and Nebraska, where they thresh from the stack, somewhat lower price is paid, as only about one-third as big a crew can do that.

The pay per bushel differs somewhat on different places. It sometimes depends on the supply and demand of machines. If there are plenty of machines and poor crop the average might only be 10 cents a bushel. But if there is a heavy crop and machines are scarce, then the price might jump up to 14 cents a bushel, just to get other machines to move over there. I heard of at least one place in North Dakota that paid 14 cents, though most pay 10 and 12 cents.

The expenses of one of the biggest outfits will not go to more than $150 a day—wear and tear of the machine also included; that is, of course, if the darn thing don't go on strike, and give the men a rest too often during the day.

So we see that the owner of the outfit will clear more at an average than what he pays out in expenses. Sometimes he will clear nearly twice the amount of what running it amounts to. I know of one small machine (36-in. cylinder and eight bundle teams) that threshed 4,000 bushels of oats in one afternoon. Four thousands bushels at six cents a bushel makes $240. A little oats was also threshed at six and will not go to much over fifty dollars. So there we see what Mr. Boss made in a few hours only.

I know another machine which threshed 92,000 bushels in 30 days. More than nine-tenths of this was wheat paying 10 cents in one town and 12 in another. A little oats was also threshed at six and eight cents a bushel, but if we average it up, will come very close if we figure the whole at ten cents a bushel. That makes $9,200. The expenses of that rig was never more than $140 a day, which makes $4,200 and gives the Boss a little nice profit of $5,000 in 30 days, while each of the men made a little over a hundred, at the rate of $3.50 a day.

"Well," you say, "he has got to pay for the machinery." O, yes, let that be, but also remember that into the $140 was figured $15 a day to pay for the machine. And, knowing how long a separator and an engine lasts (that is if the job isn't too rotten altogether, because then it might not last but a few days) this is a rather round figure.

That this above mentioned "thresher" made about $5,000 I know to be a fact because I happened to work for the farmer the last couple of days he was threshing. Of course he did not tell us how much he made. All he told us was how much they threshed in 30 days. The rest we could figure out for ourselves—besides that I happened to get the average expense a day from the separator man.

Besides this threshing the "thresher" usually owns anywhere from four and five hundred, to sometimes up to four and five thousand acres of land. Good many of them own more than one rig. Two big rigs might make $10,000 in 30 days—for the boss.

Now, then, is it any wonder then that the threshing crews are beginning to kick—when they know how much the boss makes on them? Is it any wonder that they don't like to sleep in the barns and haystacks any longer, but are demanding a decent place where to rest their weary bones after a long and hard day's work? Is it any wonder that those "lousy threshers" are beginning to shake themselves-and have this year lined up by the thousands in the Agricultural Workers Organization of the I. W. W. They are be ginning to feel that if it wasn't for the fact that they are robbed of what they really make they wouldn't have to go hungry the greatest part of the year. From Kansas to the Canada Border.

In order to be able to describe a few points from the life of those men who take up this kind of work, and in order that it may be more convincing I will mention a couple of my own experiences. I will try to bring out whatever might seem of interest—not only to the migratory worker but also to those who never yet worked by the light of "farmer's sun" (the moon) or by the shimmering glimmer of a burning straw-stack.

The best place I got a job in was Philipsburg, Kansas. It was the best because there were just then very few men, but quite a few farmers wanting men—that evening I went there. There were as many as fifteen farmers looking for from one to four and five men each, and there were only about five men ready to go out and get sun-baked in a header-box.

"How much you pay? How many hours you work? How do you sleep out there?" and a good many other questions were put to the farmers which all were answered quite satisfactorily. It was just about the most ideal town I happened to run against as far as getting a job. The grain was ripe and somehow hardly any men at all happened to be around just then. The wages were from $3 up to in some instances $3.50 and $4 for ten to twelve hours' work.

In talking about hours I heard one farmer come into town in Philipsburg and say, "I've got a heleva good man out there; he's a damn good worker, but he won't work but eight hours." Take that as a hint and don't work but eight hours a day next year.

Taken at an average the Kansas farmer is, I believe, more of a human being than what the Dakotans are. I worked in Kansas a week and there I slept in the best bed in the house, and was treated comparatively fairly. In North Dakota, up to the Canada line—as well as the other side the line, too, of course—the hay-stack or cold tent, an old barn or a filthy vermin-infested bunk-car is good enough for the "pesky go-abouts" who takes up the harvesting or threshing.

So we see there is a little difference between the people and the conditions in different states. In leaving California with its rotten bundle-of-a-bedding-on-the-back-policy and coming to Kansas sleeping in a good bed in the house it feels a little different. But as soon as one keeps on going north it soon changes again. Already in Nebraska it seems to be a little different. Although they let you sleep in the house the atmosphere seems to be changing.

I worked in Nebraska one whole day. But that Nebraska farmer wanted us to stack bundles—to throw the bundles up about four stories high on one egg each meal. But nix on that. I swear I could eat from four to six instead of only one. But there were only five eggs on the table, and there were five of us to eat. Out of the five eggs I grabbed two one meal and three at another, but that didn't help. Next meal there were only five eggs again. And the next morning the two hired men (I and one other, who, by the way, paid $2.50 for a card out of the $3 he made) walked down the road, cussing the farmer's one-egg-a-piece-a-meal and four stories high bundle stacks.

Going north we soon found that most all the men were drawing themselves towards the Dakotas. Nobody seemed to like the Nebraska stacking. And can you blame 'em if they didn't get but one egg each meal like we did? The cost of the eggs at that time was 12 cents a dozen.

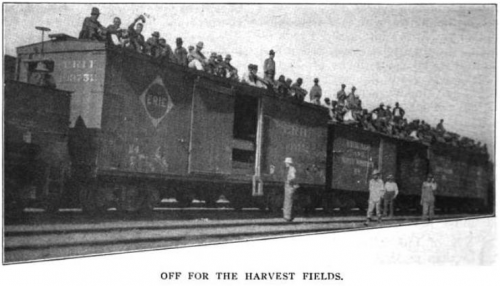

On the way northwards as many as three and four hundred men on one freight train was no unusual sight. Neither was the daily hold-ups and shootings, etc., anything unusual. Another thing which was perhaps a little more unusual was that the I. W. W. sticker could be seen everywhere. In one little town in South Dakota, its inhabitants woke up one morning and found the bank, court house, sheriff's office and the whole town nicely decorated. Of course the paper in that great burg as well as its "honorable citizens" thought that the I. W. W. was about to take charge of the town.

A little northwest of Minot is a town which for some time was surrounded by thirty deputy sheriffs waiting and watching for the I. W. W.'s coming to take charge of the town. But in the meantime those awfully feared, hated and bespatted wobblies were organizing on the job-sending in applications and fees for dozens of members through the post-office of that same town. The deputies only guarded the town, and not the threshing machines (and they couldn't pitch bundles with clubs and guns if they wanted to) nor even the bundles for the go-about-cat.

In a good many other places the powers-that-be had arrested the men and driven them out of town if they suspected that there were any of those "dangerous agitators" among them. But steadily hundreds of delegates have initiated member after member, and by the time all the threshing is over there will be at least 3,000 new members lined up through the harvest country this season.

The chief of police in Minot, N. D., for instance, thought that he would stop the organizing by giving a few of us ten days in the chain-gang. And a good many have served thirty days in different towns. Some chiefs have had their thugs out after the organizers—but all in vain. The more arresting and the more brutalities handed out to the slaves the more discontented have they become.

This year they have raised the wages from fifty cents to a dollar more a day. They have shortened the hours from one to three hours a day—in many instances. They have shown the farmers and threshing bosses that they must pay more if they want the grain harvested or threshed. They have raised a general cry of discontent, sounding its echo into the polished chambers of the big land lords; into the drawing rooms of the business men and the commercial clubs. They have shown that in organization there is strength even when it comes to be worked out up in the wilderness of the great big, wide and endless prairies of North Dakota.

This year there were about two hundred delegates; next year let it be one or two thousands of them and then the result shall be so much greater. We must remember that for every step that is taken it brings us so much closer to the goal, that goal when we will be thoroughly organized, organized so that we will be able to get a slice of that $5,000 the threshing boss skins off our backs inside of a short period of 30 days.

There is no hold-back in this—if the workers only want to do it. Anyone sleeping in a haystack after having done a hard day's work, as they do in North Dakota, ought to feel that there should be something done—especially on such mornings as it is a freezing temperature, with snow on the ground.

Nearly every year there is some grain left somewhere both in North Dakota and in Canada, which has to stand in the shock over the winter—because many men leave as soon as the snow comes, and it is impossible to invite them to come back. But, believe me, if they had a warm and clean bed waiting for them, and a good five dollars a day for ten hours' work, then there would be all kinds of men who wouldn't leave because of the snow nor anything else. But as long as those "crummy hoboes" have to work night and day for a comparatively small wage and sleep outside, and always be in a rotten condition and environment—that long will it also be hard to keep them when the snow comes.

However, this can only be done by the workers themselves. They themselves must force their employers to come through with what they need—more pay, shorter hours, better food and a good, clean bed to sleep in. And if they don't come through fold your arms and use the best methods you know in order to make their boss lose money and see that it is a losing game to fight labor.

The Industrial Workers of the World has become a menace to the grain growers all through the middle states. Never before have they had their hands so full as they have had this year. In Kansas they have tried out a new invention; a "header" which threshes the grain as it goes along and can be operated with two men and eight horses. This invention, so says the papers, will do away with the great clarion call of fifty thousand harvest hands every year, as the farmers can operate that machine without any outside help at all. In North Dakota they are going to have negroes next year. All this because the harvesters and threshing crews have at last begun to fight for more wages and better conditions.

But we shouldn't take such bluffs seriously. When next season comes the farmers all through the grain belt will wear their usual smile when they see the freight trains loaded down with men, coming from far away to help them with their grain. And that will be the time to come back on them with a much bigger and a much more serious bluff—a demand for twice as high wages as they ever paid before.

[Photograph of harvest workers on train added.]

SOURCES

The International Socialist Review, Volume 16

-ed by Algie Martin Simons, Charles H. Kerr

Charles H. Kerr & Company, July 1915-June 1916

https://books.google.com/books?id=9VJIAAAAYAAJ

ISR December 1915

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=9VJIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

"Threshing Wheat" by Nils H. Hanson

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=9VJIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol 4

The Industrial Workers of the World, 1905-1917

-by Philip Sheldon Foner

International Publishers, 1965

https://books.google.com/books?id=e-KlAAAAMAAJ

Always on Strike: Frank Little and the Western Wobblies

-by Arnold Stead

Haymarket Books, Dec 15, 2014

https://books.google.com/books?id=zTjvBwAAQBAJ

IMAGES

IWW Membership Card

http://www.iww.org/content/red-card

Threshing Wheat, ISR, Dec 1915

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=9VJIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

History of 400 A. W. O. by E. Workman, 1939, Cover

https://archive.org/stream/HistoryOf400A.w.o.TheOneBigUnionIdeaInAction/...

AWO, Off for the harvest fields, ISR, June 1915,

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=7Ko9AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcove...

See also:

History of "400" A. W. O.

The One Big Union Idea in Action

https://libcom.org/library/history-400-awo-one-big-union-idea-action

```````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vFRpgjGLgxs width:420 height:315]

```````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_gMwlUNQDBA width:420 height:315]

```````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````