I Am Alien

(This is the second installment in the serial true-life tale "I Am Alien," recounting the sojourn to the September 20, 2019 hoedown at Area 51, there to meet the alien. Installment one went up here August 12.)

Now having received the blessing of The English Patient, things were calmer, here in the car.

Neither Al nor I had ever really believed this mission to be wise, or even sane. We’d more or less bulled one another into it, until suddenly we were actually doing it. But why? That was the nagging question. Nagging worse than those scolds in The Taming Of The Shrew, or even Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. Because when you burn in a fire, what you really want to do is lie in bed. Not that sleep will often come, but maybe at some point it will, and then life will be okay. Because you will be in oblivion. Driving 900 miles across some of the most hellish terrain in all creation to join a bunch of brainleaks at Area 51 who are going to charge like those people in Zulu to try to make the alien come out: that is pretty much the opposite, of lying in bed. But now that The English Patient had vouchsafed upon us a visitation, there could be no doubt: it was right, that we got out of bed.

It began like most everything does these days: with a tube. On June 27, in a tube of the Faceborg, appeared a post commanding a mass gathering at Area 51, there to make the alien come out. All souls would gather in the Amargosa Valley, between 3 a.m. and 6 a.m. PDT, on September 20, 2019. They would then flood all of the zones, and the military, as well as the alien, would be powerless to stop them. “Storm Area 51, They Can't Stop All of Us,” the post did say. And: "If we naruto run, we can move faster than their bullets. Let’s see them aliens.”

A “naruto run” is a form of propulsion favored by the anime character Naruto Uzumaki, and involves running with arms stretched behind, head down, torso tilted forward. An anime character is not a human being, no matter what so many  people may think, and so it is unknown whether this will work with a human. Also, the notion that naruto running will obviate bullets, that would probably work out about as well as it did for the Ghost Dancers of the plains, who donned special ghost shirts believed with their spiritual powers to repel bullets, except nobody told the bullets, and so they passed right on through anyway.

people may think, and so it is unknown whether this will work with a human. Also, the notion that naruto running will obviate bullets, that would probably work out about as well as it did for the Ghost Dancers of the plains, who donned special ghost shirts believed with their spiritual powers to repel bullets, except nobody told the bullets, and so they passed right on through anyway.

Nobody much paid attention to the Storm Area 51 tube for several days. By day four, for example, only about 40 people had signed up. Then, the tube exploded. People streamed in there like the place was passing out free cocaine. By mid-July more than a million people had come into the tube to vow to swarm at the appointed place and time onto Area 51, there to make the alien came out. By then a fellow had emerged claiming to take credit for the tube: young Matty Roberts, a video-game form of human, who insisted it was just a joke, one that had bumbled into his brainpan while listening to the violently insane Joe Rogan—“basically what you’d get if a less-neurotic Marc Maron and a less-manic Alex Jones had a baby who looked like a muscular thumb”—as Rogan took a break from fellating the Klan to provide air-space to a couple of Area 51 obsessives: Bob Lazar, an ex-pimp who claims to have crawled around on an Area 51 alien spacecraft that runs on an antimatter reactor powered by a thing called Element 115; and Jeremy Corbell, a hallucinating black-belt who mates computers with doors and films people who are barking mad.

By the time Roberts revealed his identity as creator of the tube, he had been seized with The Fear: everywhere were people ululating in a frenzied St. Vitus Dance for the alien, while the partypooping US military was meanwhile carpetbombing that it didn’t care how many people tried to swarm, all those coming into the Area would go down in so much carnage it would make the denouement of The Wild Bunch look like Candyland.

Then the FBI came looking for Roberts. "So, the FBI showed up at 10 a.m. and contacted my mom, and she calls me like, 'answer your phone the FBI is here,’” he said. "I was kind of scared at this point, but they were super cool and wanted jujst to make sure that I wasn't an actual terrorist making pipe bombs in the living room." Roberts pulled the plug on his Swarm page, but it didn’t matter, the Swarm showed up elsewhere in the tubes: the advance on the alien, it would not be stopped. By mid-August more than three million people had pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honors, to congressing in Area 51 on September 20, there to declare the independence of the alien.

The swarm on the Area first fired my own personal neurons in early July, when Bezos published an article soberly examining what might happen if all these people—at that time but a mere half million—actually showed up. I understood at once that I should be there now, as mass public strangeness, it can make, for some of the very best, of the Stories. Further, I knew it wouldn’t really matter, whether Woodstock/Altamont numbers of humans showed, some number less than that, or even nobody at all. It was just too weird, to pass up.

I also thought of Al, a woman with a lifelong and persistent interest in the alien. She had personally communed with the alien while still quite young, though I knew nothing of this encounter, as she would not tell me. “You don’t need to know everything,” she’d said. “It’s between me and the alien.”

But when I mentioned the idea of her revisiting the alien in the Area 51 swarm, she scoffed. Wouldn’t even consider it. That made it a challenge. And so, like Elizabeth Warren—who may or may not be an alien; after all, it wasn’t until she was well into her 40s that she stopped identifying as a Republican, as to that point she believed “those were the people who best supported markets”; and really only a being not of this planet, could make that sort of mistake—I persisted. Al then erected a vast Maginot Line of objections, which I tried to evade by coming in through Belgium, as did the Germans, but it was no good, she fortified there too.

Soon enough I wearied, and was no longer interested in the alien. At which point the tables loudly turned. Al suddenly roared in and announced the mission was on. I said I didn’t wanna, I didn’t care any more about the alien, I just wanted to lie in bed, but she said she would come over with a taser on full power unless I gave heed to her brainshower. Which was this: she had concluded Roberts was a phony, a fake, a fraud, he had never come up with the alien idea at all: she knew this because Roberts was now disavowing the entire project, and was instead attempting to organize a three-day ersatz Woodstock music-and-arts thing called Alienstock, for the same weekend as the Swarm, and in a little Nevada hamlet called Rachel, where the 90-some inhabitants had gone Vesuvius and vowed they would blow up their own town, rather than allow a bunch of alien-addled froot loops in there. It wasn’t Roberts at all, don’t you see, said she, not Roberts at all, who went to the tubes to announce and promote the Swarm, it was instead the alien herself. “She’s sending out an ‘I’m Calling You,’ just like in that movie Baghdad Café,” Al announced her vision. “And so it would be a betrayal, not to go there.”

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dbax86veenA]

Okay, sure, then. Why not? Let’s go see the alien. But that wasn’t the end of the story. There remained many near-death experiences, long before we ever hit the road, more such experiences than there are lilies of the field: as Al’s wisdom, it clashed, with mine.

For instance, there was the matter of the route. To my mind, a non-batshit person, traveling from Butte County to Area 51, would drive 80 into Nevada, and then motor down 95, until taken into custody at the gates of the Area 51 forbidden zone. That’s a little over 500 miles, and requires a time investment of about eight hours. Maybe more if you didn’t have any driver’s licenses, which we didn’t, and therefore would rigorously adhere to the speed limit at all times. And also if you didn’t want to pee in the car.

But Al was having none of that. She insisted that “we have to approach the alien from the south.”

“Why?” I asked.

“You just do,” she said. “Everyone knows that.”

Her route required a saneless sojourn all the way down 99 to 58, then a numbing Sahara-like ordeal through such garden spots as Barstow and Needles, to Nevada 95 north, and up through Las Vegas, until, after passing through the city of sin, would arrive a bunch of roads with names like Mesa and Short Pine and Groom Lake, all of which on all the maps said in big red letters Restricted Use Road, which meant that in attempting to traverse them we would be shot down like Bennie at the end of Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia. So, before we inevitably received more bullet holes than Faye and Warren at the close of Bonnie And Clyde, we would have driven over 900 miles, across 15 hours, and then only if we recurrently shot speed in both arms, and never stopped.

I suggested we could still “approach the alien from the south” if we took the quicker 80/95 route, and then just overshot the Area some, until we were due south of it, at which time we could then come up, but Al was adamant that this plan was worse even than Custer’s at the Last Stand. She provided me no real reason; I just didn’t get it. Until finally I understood.

“You just want to go to Las Vegas, Annie Oakley, that’s what this is about, you want to go to the roulette tables and try to make a midas pile. You have a roulette jones. You maybe don’t even want to see the alien at all.”

Al then went to the pencil, but I was quick, and avoided a stab that might have impacted the femoral. Al is well known for penciling people who have gone Wrong. And I had become one of them. Because no doubt I was right. For Al and I are both people of the wheel. Roulette is the only real game, but it is extremely dangerous, because in it you can sync with the universe, and in there know “ahead” of “time” exactly where the ball will fall, and there’s no electric quite like that, but, and like all the best things, this experience  is fleeting, and you have to be strong as twelve bastards to intuit and accept when you’ve moved from knowing, to just thinking you know, and so then from the table walk away, before you have there spent all of your money, and even more than that, and so have to go back to the garret, and there write eleventy-billion words about living underground, like that roulette-head Dostoyevsky, in order to make the rent. I had never lost money at roulette, but then I’d only gone to the wheel about a half dozen times, and I knew for sure if I went up there now, burned, odds are I would leave having to live under a railroad bridge.

is fleeting, and you have to be strong as twelve bastards to intuit and accept when you’ve moved from knowing, to just thinking you know, and so then from the table walk away, before you have there spent all of your money, and even more than that, and so have to go back to the garret, and there write eleventy-billion words about living underground, like that roulette-head Dostoyevsky, in order to make the rent. I had never lost money at roulette, but then I’d only gone to the wheel about a half dozen times, and I knew for sure if I went up there now, burned, odds are I would leave having to live under a railroad bridge.

“We can’t go in there, Al,” I urged. “It will be worse than Lost In America. Where Linda loses the entire hundred-grand nest egg at the roulette table, and then runs off with the biker, until she ends up working in a hot dog hut in Arizona, where David meanwhile works as a crossing guard.”

“I never said I wanted to go to any casinos,” she insisted. “That’s all in your head. This is about the alien. Only the alien.”

“Right. Sure. We’ll see.”

I didn’t have any nest egg, and so wouldn’t have to fall far to reach hobo, but Al has a house, and other status symbols of our time, and I was tempted to rifle her bag, to see if she’d stashed her deed in there, but she has firearms, and knows how to use them, and so I hadn’t yet managed an opportunity where I could get in there, without risking receiving a round.

But at the moment no one was shooting anyone, as we basked in the blessing of The English Patient. I was preparing to bloviate upon the Nature and Meaning of The English Patient’s visitation, when Al decided it was time to attack my name.

“I don’t see how you can criticize my name, considering the one you’ve got,” she said. “Penelope is a fine name; it’s musical. Your name, on the other hand—Odysseus—is a dental dam. It’s impossible to get it out of your mouth. People look at that clog of consonants at the front—Odyss—and just throw up their hands, say fuck this, I’m not even going to try. Who would come up with a name like that anyway?”

“Greeks. It’s a Greek name.”

“Greeks should stay out of the names. The Greeks are okay with history, science, philosophy, drama, oracles, fate, burning cars in the street rather than paying taxes, and, yes, let’s face it: pederasty. But if they’re going to come up with a thing like Odysseus, they need to leave the names alone.

“Also,” she stabbed on, “what it means? It means to hate, to lament, to bewail, to perish, to be lost. I am not going to go up against the US military to get to the alien with some hater whose name is all about lamenting and perishing and losing. That is just too much juju of doom. So I am changing your name. I am going to call you O.”

“That’s fine.” Al was still driving; I, passenger, was still looking out the window. There were no longer any meth monkeys in view, and The English Patient had bestowed his blessing and flown on, but now I saw a snowman sitting on the side of the road. So I couldn’t really concentrate on Al’s savaging of my name, startled as I was by the  sight of a snowman in this unlivable heat. I wondered if I should ask Al to turn around, tell her I’d seen a snowman, and suggest maybe we should go back to see if he needs a ride. But then I thought better of it. Because I figured if I did tell her, about the snowman, she would attack more than my name.

sight of a snowman in this unlivable heat. I wondered if I should ask Al to turn around, tell her I’d seen a snowman, and suggest maybe we should go back to see if he needs a ride. But then I thought better of it. Because I figured if I did tell her, about the snowman, she would attack more than my name.

“Or maybe one of the other letters,” she went on. “O might still be too infected with the perishing and losing. Maybe I’ll call you Q.”

“Please don’t.” That snapped me out of the snowman. “That letter is at present grossly contaminated. By that lunatic clot of Klansman cultists who believe Hillary Clinton goes down in the basements to molest the children with the pizzas.”

“Right,” Al agreed. “It’s too bad they wrecked the letter. Q was a fine letter, when he was running Star Trek.”

“Have you ever noticed,” piped I, “that when people draw sketches of the aliens they claim to have encountered, there are almost always no sex organs—they are as sexless as Spielberg—but in Star Trek the officers and crew are in sexual congress with aliens at all times? Kirk, for instance, was in more women than John Holmes.”

“He was the worst,” Al agreed. “Though they were all always in rut. Even Data, the android; gave Tasha Yar the time of her too-brief life. Picard made it with a Borg. Spock would occasionally be stunned by some flower and go off to play the lyre and do the deed. Then there was that officer who abandoned ship for Apollo. Though you can’t really blame her. It can be hard for a girl, to resist a god.”

“Apollo was Greek,” I said. “I thought you hated on Greeks.”

“But he had a name a person could pronounce,” Al said. “Unlike you, O. Also unlike you, O, he didn’t look like the Michelin Man.”

Al was still driving, about 20 mph now, a real racehorse this woman, but she also now seemed to be hating her phone. She was glaring at it intently, and so it was good she was driving slower than rumbles a raccoon, as her eyes were not on the road(s), and if she was going any faster we would slide off into the sands, get stuck, and there be eaten by meth monkeys.

“What’s the problem?” I asked.

“I can’t get a signal.”

“Of course you can’t get a signal,” I laughed. “Not out here. As soon as there’s a signal, the meth monkeys steal it.”

“Meth monkeys can’t steal a cellphone signal!”

”Of course they can. Meth monkeys can steal anything. You know that Grateful Dead song, with that line ‘steal your face, right off your head’? That’s about meth monkeys. They do that.”

“No Grateful Dead!” she shouted. “We agreed: there would be no Dead on this trip!”

“Jeez, Al, I’m not playing it. I’m just quoting it.”

“Too close,” she snapped. “No quoting, either.”

John Lennon, that’s who was presently playing in the music, there in the car. Not very loud. Grousing about “as soon as you’re born/they make you feel small.” I assumed Al would have no problem with him. But, as so often with Al, I was wrong.

“And fuck John Lennon,” she said.

“Excuse me?”

“Fuck John Lennon. He beat Cynthia, and he ignored Julian. He’s whining in that song about being made to feel small, but that’s what he did to his own son. That always pissed me off. I feel like he was shitty to Yoko, too. I’m not sure he changed much, just put on a more acceptable face.”

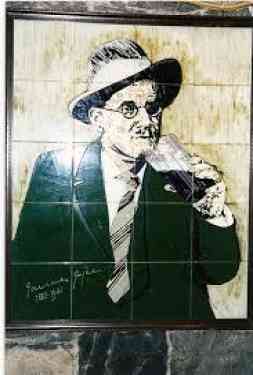

“Yes, well, with the artists it’s best not to look at their lives; just go with the art. Otherwise you find out stuff like when Joyce was  writing Ulysses, his wife and children were peeling paint off the walls, to eat it, because Joyce had forgotten to go out and cadge money off someone for food. Joyce himself lived on liquor and cigarettes, so he didn’t need any food, and people were always shoving booze and smokes his way, because he was ‘Joyce.’”

writing Ulysses, his wife and children were peeling paint off the walls, to eat it, because Joyce had forgotten to go out and cadge money off someone for food. Joyce himself lived on liquor and cigarettes, so he didn’t need any food, and people were always shoving booze and smokes his way, because he was ‘Joyce.’”

“Well, fuck him too then. Sick of these men who get away with this shit.”

“The women aren’t much better. Look at Anne Sexton.”

“She was mentally ill, though.”

“They’re all mentally ill. Else they’d leave off the scribbling, and do something real, like build a boat.”

“No one’s going to be building a boat out here.” Al gazed anew at the wasteland. Because why should she look at the road(s)? She was only driving. “The whole place is allergic to water.”

“Sometimes there’s water,” I said. “There’s even a sea. The Salton Sea.”

“Which is pathetic,” Al countered. “It’s an embarrassment to seas. Like the Sutter Buttes are an embarrassment to mountains. Some things shouldn’t even try.”

I supposed that was true.

“At least you don’t have to worry about being mentally ill,” Al said, “because you’re not an artist. You’re just an ex-journalist now scuffling as a law dog. But you might have been, if back in high school you’d taken the art class, instead of the journalism class; then you wouldn’t be on this trip, you’d be under a bridge somewhere, cutting off your ear.”

“I could still do it,” I said. “I don’t know if there’s been a journalist who cut off his ear. I would be the first.”

“Well, don’t do it in here. I don’t want you getting blood all over my car.”

“Fine. I’ll wait till we’re in a motel room.” I’d never really thought about cutting off my ear, but now: why not? My hair grows down over my ears: who would notice? Besides, at the rate we were going, Al would be severing one or more parts of my body, before this trip was through. Why not get a head start? “I’m thinking I’ll cut off my ear and give it to the alien.”

“What would the alien do with your ear?”

“I don’t know. But it would be interesting to find out.”

“That’s just grotesque,” Al sneered. “You’re not cutting off your ear and giving it to the alien.”

“Fine. I’ll give it to you.”

“Are you calling me a whore?” Al exploded.

“What?” Jesus! Being in a car with Al was like riding around with a bomb.

“Van Gogh gave his ear to a prostitute!”

“That’s fake news, Al. He gave it to a maid.”

“A maid in a brothel!”

brothel!”

“No, Al, I don’t think she worked in a brothel. The way I heard it, she was just a young woman who’d been torn up by a rabid dog, and was struggling to pay her medical bills.”

“And an ear was supposed to help her how?”

“I don’t know.” Yes. That was indeed the stumper. “Maybe she could carry it around with her, and then the next time a dog attacked, she’d heave the ear at the animal, to distract it.”

“There is so much wrong in that story, O. Like, if she was bit by a rabid dog, she would have died.”

“Not necessarily. I guess you don’t always get rabies, when bit by somebody rabid.”

“Well I am not going to find out,” Al said. “If anything rabid comes around me, I am shooting it in the eye, from a long ways away, like Atticus Finch shot Tim Johnson.”

“No one has a dog named Tim Johnson.” This had long troubled me. “I think Lee was saying something there; Tim Johnson is pretty close to Tom Robinson.”

“Not that close. It wouldn’t work in a poem.”

“It might. Why don’t you try.”

“I don’t do poems. Some things a person shouldn’t do. I shouldn’t write poems, John Lennon shouldn’t ignore his son, the Grateful Dead shouldn’t play in my car, and you shouldn’t cut off your ear.”

“I don’t have a knife anyway.”

“I do,” Al said. “But you’re not getting it.”

“I’ll just buy one,” I decided. “Meth monkeys always have knives, so the stores out here, every one I bet is crawling with knives.”

“To go in a store you’d have to get out of the car, at which time you would die instantly,” Al said. “Forget about the knives. Just keep your ear. Who knows, someday you might hear something.”

I was tempted to tell her about the snowman, who seemed to be surviving in the heat, but the time did not yet seem right. Not when we were discussing knives.

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NXX_4RUsL7U]

It had been dark for some hours, but still we were not to Needles. This was due to the fact that I could not wrest the wheel from Al, while Al could not drive faster than waddles a duck. I had, some eons back, nearly convinced Al to let me drive, but then I let slip about the snowman I’d seen, lounging there in the sands. Cue Al roaring. If I could not prevent myself from seeing a snowman in the desert, Al deafened, definitely I was capable not of piloting an automobile anywhere other than the boneyard.

“Al, we are just going to have accept things like snowmen,” I’d insisted. “I mean, the visitation of The English Patient, didn’t that make it burningly clear that these are the days of miracles and wonders?”

“I told you we’re not in a Paul Simon song, O, back when we reached ‘you can call me Al.’ We’re in the goddamn Mojave! Paul Simon could never have survived here, he can barely draw air a mile west of the Hudson. It’s true that his ‘miracles and wonders’ song has the desert in it, but that doesn’t mean he’s ever been in a desert, and even though it’s also true that you are totally a boy who belongs in a bubble, like that song also says, none of that means I have to accept that we have flounced into some fairyland where it is perfectly normal for snowmen to be out there dancing in the dunes.”

“It was only one snowman,” I corrected. “And he wasn’t dancing. He was just sitting there.”

“I can’t believe we’re sitting here hair-splitting about whether your hallucination was sitting or dancing.”

And so on. It was only now, hours later, that she at last relinquished the wheel. And then only because she’d at last played out, like a horse flogged too fast, too far. Al, in the driving: she was for the knackers.

I’d noticed for some time, her grimacing, grunting, groaning, there in the driver’s seat, as gingerly she gyrated her glutes. For a while I said nothing. Because of the weapons situation. Finally I asked, as politely as I could muster: “Are you having a seizure of some kind?”

“My ass has gone wrong,” she confessed. “It’s in spasms, and also it’s numb.”

“This sounds like a job for Medicine,” I said. “You should pull over and let me drive, then get into the first aid kit, find something in there to return your gluteus to maximus.”

“But you’re seeing snowmen.” She was skeptical.

“That was hours ago,” I reminded her. “Besides, it’s dead dark now, so it’s not likely I’ll see any snowmen, even though, yes, true, they’re white. But I doubt I’ll notice any, unless the headlights shine right on them.”

She eased the car to the shoulder—it didn’t take a lot of easing, not from 25 mph—and then we sat there. “Probably we can change seats by getting out of the car, rather than climbing over one another, like we did last time,” I suggested. “The sun’s been down for several hours now, so presumably the temperature out there is no longer life-threatening.”

“I don’t know,” she said doubtfully. “I don’t think we should go into it all at once. Let’s start just rolling down the window a little.” Then she girded her loins, though her loins were numb and in spasm, and electrified her window down an inch or so. No death rushed in immediately. So she gave it another inch. Still we lived. The air coming in was inhumanly hot, but not fatally so. So she electrified the window all the way down into its slot, and then, with a groan, she popped open the door, and walked out into the night. I did the same. But without the groan.

It was an oppressive hot air bath out there, close and clingy, but I didn’t feel like I would imminently require last rites. Al was off a ways from the car, doing something with her nether regions that looked like it might be at home around a stripper pole. I was tempted to comment on this. But didn’t. For fear if I did, I would need said rites.

Instead I walked across the road, to where the Mojave National Preserve began. Established because: it was important to save the sand. Out there, in the dark, it stretched away, the Preserve, miles to the north. And, north of that, I knew: he was out there.

“Who’s out there?” Al too had crossed the road, and was standing beside me: apparently, I had spoken aloud.

“Von Stroheim,” I said.

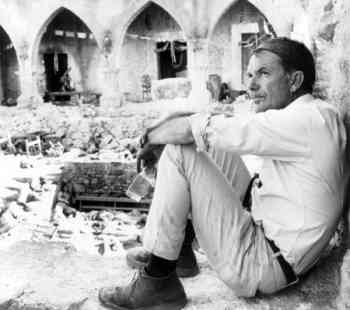

“What is von Stroheim?” she asked warily. “Is it a kind of snowman?”

“Erich von Stroheim,” I said. “He’s filming the last sequence of Greed out there. Which is what he’s calling his adaption of McTeague. Two months he’s filming in Death Valley. He was the first of the location obsessives: why, decades later, Coppola will go mad, out in the jungles of the Philippines. Hollywood in von Stroheim's time filmed desert scenes in Oxnard. But von Stroheim needed the thing itself. He took cast and crew out to Death Valley, in midsummer, a hundred miles from any town, any road, hotel, food, running water. People collapsed of heat exhaustion every day. A third of the crew had to be shipped back to LA. Film melted, cameras melted. It got up to 123 degrees out there. Kinda like it was today, down here. But they didn’t have an electrified car to retreat to. McTeague has gone all to the bad, and, pursued by a posse, has gone into the Valley. All of the posse but Schouler, McTeague’s former friend, a man also gone to the bad, turn back. Schouler keeps after him. McTeague has but a horse, some gold, some water, and his little bird, in a little cage. A canary. The bird represents the kernel of goodness in McTeague. No matter how bestial he becomes, and he goes pretty bestial—like, he kills his wife—he still cares for the bird. We’re in 1899 here. Forty-five years later, after a hard day killing the Jews, Heinrich Himmler, he would come home, and, before entering his house, remove his jackboots. Because he didn’t want to awaken his little bird. That was Himmler’s kernel of goodness. Because everybody has a circle of compassion. That’s what Philip Hallie said. He’s a man who decided to try to find out what makes people good, rather than bad. And he cited Himmler as an example of somebody who, though very bad, had compassion, at least for something. That bird. Some people, like Himmler, have a circle of compassion very small; the circle of others, encompasses all the universes. But everybody has one. No matter how small. Like with the Whos and Horton. Because 'no matter what they tell you/there’s good and evil in everyone.' That’s what Van Morrison says. Schouler catches up with McTeague, and they fight. Scheuler pulls out a gun, McTeague grabs the gun, and brains Schouler with it, kills him. But before Scheuler dies, he handcuffs his wrist to McTeague’s. So McTeague is handcuffed to a corpse. In the fight a bullet had gone through his last canteen: no water. His horse: dead. McTeague is out in the center of Death Valley. Alone. He’s going to die. He pulls the birdcage from its protective sack, opens it, takes the bird out, kisses the bird, then lets the bird have wing. But the bird flutters back onto the empty canteen. The bird is going to die too. Von Stroheim spent days filming this fight scene. He too wore jackboots, well, riding boots, and he would beat at them with a riding crop, while shouting at cast and crew: 'More death! More death!' He got what he wanted. Course, then he turned in a film ten hours long. That was seized by the studio. Cut to ribbons. Was a commercial failure. And a few years later he was out of directing, blacklisted, reduced to playing character parts as German villains. Today the search for the original uncut Greed is like the search for the Holy Grail. Because it’s considered just as valuable. But it’s no doubt just as lost.”

a gun, McTeague grabs the gun, and brains Schouler with it, kills him. But before Scheuler dies, he handcuffs his wrist to McTeague’s. So McTeague is handcuffed to a corpse. In the fight a bullet had gone through his last canteen: no water. His horse: dead. McTeague is out in the center of Death Valley. Alone. He’s going to die. He pulls the birdcage from its protective sack, opens it, takes the bird out, kisses the bird, then lets the bird have wing. But the bird flutters back onto the empty canteen. The bird is going to die too. Von Stroheim spent days filming this fight scene. He too wore jackboots, well, riding boots, and he would beat at them with a riding crop, while shouting at cast and crew: 'More death! More death!' He got what he wanted. Course, then he turned in a film ten hours long. That was seized by the studio. Cut to ribbons. Was a commercial failure. And a few years later he was out of directing, blacklisted, reduced to playing character parts as German villains. Today the search for the original uncut Greed is like the search for the Holy Grail. Because it’s considered just as valuable. But it’s no doubt just as lost.”

“Jesus Christ that’s depressing,” Al said. “What possesses you to hang on to this shit?”

“Don’t you know Greed?”

“Of course I do. I saw it in college. But I’m not going to wallow in it every damn day. Jesus! You’re why people shoot heroin.”

“It’s just that we’re out here," I said. "That’s all. And so is he. He’s out there. Waiting. For the dawn. Then he’ll be back at it. ‘More death! More death!’ Things like that, they don’t fade. The thing itself. All of the time, it is always going on, we’re just ordered to notice it, only, minute by minute. But that’s not how it really is. It’s ‘everpresent everywhere.’ More Van Morrison. And so is the space. Which is why The English Patient, who’s flying over the desert of North Africa, could so easily fly over here, the Mojave. Places like the desert, where all else is so sparse, it’s easier here, to perceive, the various times, spaces.”

“You’ve been into the mushrooms,” Al decided.

“No,” I said. “But I’m thinking that when we near Needles, we should both get into them. Not so soon that we can’t deal with the desk clerk. But timed so they come on when we reach the room. We will deserve them, after this day.”

And it would have worked like I’d said, too, except Al had an explosion when we pulled into the parking lot of the motel I’d chosen.

“I am not staying in the Bates Motel!” she shouted.

“Al, it’s the Bateson Motel,” I said. “It’s just the neon of the ‘O’ and the ‘N’ are burned out.”

“Yes, which is a fucking sign like from the lord himself that only people who want to be stabbed in their beds would want to go in there!”

“Al,” I reminded her, calmly, as the pinks and the purples, there in the vision, they began to dominate, “Norman doesn’t stab people in their beds. He stabs them in the shower.”

“You are a lunatic! We are not staying here!” And she proceeded then to Yelp in her phone. I’d previously researched the few lodgings available here in Needles, and had settled on the Bateson Motel as the most reasonably priced, at least among those not clearly frequented by meth monkeys. How was I to know Norman was now running the place? Al was getting kind of this soft psychedelic madonna glow to her face, the light from the phone softly bathing it, as she searched for a place we could stay without somebody going all redrum on us. I wondered if there was also an Overlook Hotel in this town. I wondered too if Al had ever posed for a pieta. I was going to ask her, but then she said, “Okay, I found it. We’re going to the Red Roof Inn.”

“I don’t know, Al,” I said. “’Red Roof’—that could be blood. The red. On the roof. It might be dripping there. Like a Vincent Price place. Didn’t he have a house that dripped blood? Maybe that house is a motel now.”

“That was Christopher Lee, you nitwit. Vincent Price had The House of Usher.” She gazed ahead intently. “But then it fell.”

“What about The House At Pooh Corner?” I suggested. “Look in the Yelp and see if there’s one of those here.”

“There’s too much purple in the phone,” she shook her head. “Let’s just go to the Red Roof. I checked, and nobody’s reported being stabbed there recently. We need to get in there before the mushrooms completely take over. It’s only about a mile from here. I think. Can you do a mile?

“I am Marathon Man,” I announced.

“Stop with that. Hideous stabbing, in that movie.”

“But not in the marathon man himself. He didn’t receive any stabbings. Also he threw the diamonds in the sewer.”

“Shut up and get to the Red Roof.”

I did that. But Al, she could not maintain. As we motored the mile, neath all the pretty lights, she began giggling, softly chanting ‘redroof redrum redroof redrum.’”

“If you say that when we get to the desk clerk, we will go to the jail,” I told her.

“I’m just getting it out of my system,” she said. “When we get to the desk clerk, I will be sober as a judge.”

“Did I ever tell you that I used to run into Ann Rutherford in the supermarket, back when she was a judge, with her cart groaning under the weight of numberless mammoth jugs of vodka?”

When we pulled into the parking lot of the Red Roof, it looked eerily familiar.

“I’ve been here before,” I said.

“Yes,” Al agreed.

“This is the motel at the end of Twin Peaks: The Return.”

“No,” Al faltered. “I don’t think so. Because I don’t see myself  standing over there by the pillars, like Diane did, when she was sitting in the car, in the parking lot of the motel that looks like this one. Also,” she added, rallying, “it’s not that motel, because there’s not going to be any fucking. In the Return motel Diane didn’t know until the fucking that she would be leaving Dale, who was really now Richard, but I don’t need to get anywhere near any fucking, to know you’re not for me.”

standing over there by the pillars, like Diane did, when she was sitting in the car, in the parking lot of the motel that looks like this one. Also,” she added, rallying, “it’s not that motel, because there’s not going to be any fucking. In the Return motel Diane didn’t know until the fucking that she would be leaving Dale, who was really now Richard, but I don’t need to get anywhere near any fucking, to know you’re not for me.”

This was not news. I knew that the first time there was the taser. As we grappled with the doors, Al announced that she would do the talking to the desk clerk. I, she said, would come in only if it was clear that cavalry was required. “You’ve gone to 'The House At Pooh Corner’,” she said. “You’re in no condition to do anything but not talk to me for four hours. And if we get in the room, and in the shower you start singing the 'House At Pooh Corner’ song, I swear I will come at you in a way that makes Norman Bates look like Heidi.”

“Heidi interrupted the football,” I recalled. “Men with beers went Bates.”

“Jesus,” she whispered.

The desk clerk had only one eye. There was no getting around that. Besides the one working orb, he did not have a Sammy Davis eye, a Peter Falk eye, a glass thing that rolled around in there. No. There was instead just a flap of flesh. Closed over the missing door of perception. It was a little startling. But hey. It somehow went with the rest of him. Which was large and squat and neckless and seemingly of orc heritage. But orcs are people too, you know. Van Morrison. He would say that.

Al’s plan immediately went awry when the desk clerk asked for ID, and Al produced her driver’s license, which was expired, which the clerk could discern, even with just the one eye. He asked again for valid ID, and Al slammed a credit card down on the counter, roaring, “how about this for ID?”

“We’ve moved to Nevada,” I said. That seemed like good cavalry. “The new IDs haven’t arrived in the mail yet.”

“You don’t have one either?” the desk clerk asked. His voice sounded like rocks rolling around in a can.

“Alas, I also am expired,” I said.

“We nearly expired for real today,” Al said. “With all those meth monkeys.”

“Meth monkeys?” squinted—a person can squint, even with only one eye—the clerk.

I was beginning to think we wouldn’t get a room.

“Gentlemen of the methamphetamine persuasion,” I explained. “There was a convocation in the desert. We are journalists, and were there to receive their wisdom. We do not judge. We only record.”

I felt sure this man had met some methamphetamine in his time. I think such is pretty much a requirement, there in Needles.

It was strange about the mushrooms. They wanted to purple and pink and shimmer everything else. But they stayed off the desk clerk. He was like the black and white part, in The Wizard Of Oz.

“Well,” he grumbled, “this is out of the ordinary.”

“Isn’t everything these days?” I said cheerily.

“No,” he said flatly. Well, fuck me. Cavalry like Custer along the Bighorn. That be me.

Then he ran Al’s card through his machine. Money, as they say, talks. Even, it seems, when those who have it, are spouting gibberish.

I thought we would make it to the room unmolested, but when we got to the door he said, “Hey, the name is different.”

“What name?” Al asked. I could no longer speak. My cavalry had been massacred.

“The name you signed isn’t the name on the card. You signed ‘Al.’ And he signed ‘O.’”

There was a silence as of the tomb. Then Al said: “Those are the names of the undercover. Because of the journalism.”

“Hmm,” the clerk grunted. Al shoved me through the door, before the man could come up with any more questions. Then, as soon as we got in the door to the room, she began savagely punching me in the shoulder.

“What?” I said. “I’m not singing the ‘House At Pooh Corner’ song!”

“Did you get a look at that clerk?”

“Yes,” I said. “It was either look, or go blind.”

“He had only one eye!”

“Not everybody has two eyes, Al. Some people only have one. Some have none. Some have nine. Like octopus. Or is that brains? That might be the number of the octopus brains. I do know that octopus eyes are in the skin.”

only have one. Some have none. Some have nine. Like octopus. Or is that brains? That might be the number of the octopus brains. I do know that octopus eyes are in the skin.”

“What I know is that guy had one eye because of you!” And she started pounding away again.

“I never put his eye out!” I protested. “I have never seen that man before in my life! I know sometimes I talk about dangling eyeballs, but I’ve never actually done that. That was that woman I knew, whose father was a mob guy. She was going to have her father send his guys out to dangle Jeff’s eyeball, when he ruined the newspaper, but then I would have owed him a favor, and might have someday had to pretty up Sonny in the mortuary, after he got shot on the causeway. So I said no.”

“What you should have said no to was your name!” Al raved. “That’s why he only had one eye. He’s the Cyclops! We’re in your damn Odyssey! And I don’t even remember how it goes! Much less how to get out of it!”

“Well, I think the Cyclops ate a bunch of the men,” I remembered. “Before they smoked a stick and poked his eye out. But I don’t see any sticks in this room. And I don’t really want to build any fires. Also, we don’t have any men for him to eat. There’s just us. Probably we should have brought more people.”

“What else did he do?” Al was pretty much frenzied. “He got tied to a mast because he couldn’t resist some women singing. That sounds like you. Then Calypso kept him on an island for seven years. Were all the others dead by then? I can’t remember. And wasn’t there a whirlpool?”

“There won’t be a whirlpool with us,” I said confidently. “We’re in the desert.”

“It will be some sand whirlpool!” she shouted. “Probably like in Dune, and some big fucking sandworm will come out of it!”

“We will ride the worm to see the alien.” I could picture it. And it was marvelous. “People will be in awe.”

“We need to review the Odyssey, right now, so we know what we’re in for,” Al said. “But the phone is too purple!”

“Foregt the phone,” I urged. “We can find out about the Odyssey in the morning. What we need to do now is lie down on the bed and look at the ceiling. Also.” I had a thought.” At least it’s better for you here, now, than it was in the original story. Here, you get to have the adventures. But in the original Odyssey, Penelope had to stay home all that time, weaving, I think, and unweaving, constantly. As a way to stave off suitors.”

“Right,” she said, collapsing on her back onto one of the beds. “Suitors.” Then she came up, fiercely, on her elbows, and said, “And you better not try to suit me. If you do, I will shoot you in the abdomen.”

“Suit yourself,” I shrugged.

Soon things were calmer. We were on our backs, on our respective beds, tuning into the ceiling.

“These stucco ceilings,” Al announced, “are so much nicer, when they’re moving.”

“Yes,” I agreed.

“They are always doing that. Moving. And there are always the patterns. We just don’t often see it. Like that director with his movie out in the desert. Who we don’t often see. Unless we’re you. And have a brain malformation.”

“Yes,” I agreed.

There wasn’t much talking after that. Al talked some about her theory of the alien. That the alien was ready to come out. That the alien had been the one to get in the tubes and post the Storm invitation. That the alien needed us to come help her come out. Like Boo Radley. I had my own theory. But I didn’t gibber it. I don’t always have to be the one with the theories. With the talking. Al had burned in the fire. The fire hadn’t got her house, had burned right up to and all around it, but then left it alone. Because it felt like it. She wasn’t there at the time. Had gone down the mountain. Fleeing the flames. Horseback. But when she learned the house was still standing, she was right back up there. Rode up. When the authorities came by to say she couldn’t be there, she said she had been there the whole time, she’d stayed through the fire, she just hadn’t come outside the house much, so they hadn’t before seen her. What about the horse? they asked. We never before saw him, either. He spooked, she said, ran off in the fire, but he’s back now. My house, she Aled. My land. My horse. I’m staying. They backed off. Al burned in the fire. So she can think what she wants. About the alien. About all and any of it. Except if she thinks she should stab me in the shower. Even if I do sing ‘The House At Pooh Corner.”

I thought she was asleep, when I heard her say, “Paul Simon.”

“Hmm?” I was nearly asleep myself.

“I do like the ‘Diamonds On The Soles of Her Shoes’ song.”

“So do I,” I said.

Deep in the night, I awoke—prostate on the storm—and, returning, I tread lightly over to where she’d set her shoes. Turned them over. Gazed at the soles. Yep. There they were. Diamonds.

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uf4YyXVoWeA]

“This food is good.”

Rarely never do such words emerge from a burned person. And yet there they were. Emerging from Al. From an Al jaw dropping with the weight of several flats of scrambled eggs. The eggs moving into the seemingly bottomless maw of Al via the perpetual motion machine of a fork. The fork provided by the restaurant. The restaurant redolent of the restaurant in the final episode of Twin Peaks: The Return. Which was right and meet. Because we had spent the night before in a motel redolent of the motel in the final episode of Twin Peaks: The Return.

Except, at our motel, there in the parking lot, Al, sitting in the car, had not seen herself, over by the pillars, as had Diane, Returning, sitting in the car, seen herself, over by the pillars; and also, once in the motel room, with Al and I, there had not been the fucking, as there had been the fucking of Dale and Diane, Returning; also, in the night, for Al and I, at no time had “My Prayer” sounded loudly from the ceiling, as said prayer had Returned, for Dale and Diane; and also, in the morning, Al was not now Linda, and gone, and I was not now Richard, and alone—as had happened, in Returning, with Dale, and Diane.

With Al and I, upon the hour before the dawn—we awoke then, Al and I, as all fire people do, no matter how late they may have remained awake the night before, staring in the mushrooms moving in the purple in the patterns in the stucco of the ceiling—I was still me, and Al, she was still she; and, in her she, Al announced, standing there, betoweled, in the steam of the shower: “This is what will happen next: I will eat all of the breakfasts.“

This was wisdom. For yesterday Al and I had pretty much forgotten to go to the food. And a man, he cannot live long, on road beef jerky, alone. So too, when a man, s/he is a woman.

So Al was now consuming the scrambled reproductive emanations of nine or eleventy hens. I, meanwhile, was in orgy with the bacon. There is a way, in the restaurants, of brujaing the bacon, so that the customer, he will spend all of his money upon it, and then, when his money, it is all gone, he will go out back into the alley, and there roughly roll all and every wino, to obtain the change to purchase, even but a single strip, of bacon, more. This, was that bacon. So I waved to the waitress, brought her over, and commanded her to produce all of the bacon, and at once.

It was good, that this restaurant, like the motel before it, did not precisely track Twin Peaks: The Return. Else we would, here, in the restaurant, have been forced to contend, Al and I, with several large surly yeehaws, producing weapons, of which they would need to be relieved, the weapons then dumped in the bubbling fat of the deep-fryer, so they could harm no one, except the next people to order french fries, who would then heave into chunder, from consuming rancid gun grease.

“How’s your arm?” Al asked through the eggs.

“What?” I: in my steady state: understanding not.

“Your arm!” Al sprayed eggs. “Your shoulder!” Then she calmed. Some. “From where last night I hit you.”

“Oh, that,” I said. “Fine. No pain. No bruising. Everything is fine.”

“I really shou—“

“Forget about it, Al. It doesn’t mean anything. We’re just in a story. Seemed the right thing to the guy writing us at the time. If it had been real life, it might have been a problem. But in real life you would never have done it. So we don’t have to convene some endless morning-after anger-management weep and hand-wringathon.”

Al nodded. Then avidly  dumptrucked more eggs into her being. “Also,” she managed, around the mangled remains of many chicken children, “in real life, I wouldn’t be eating eggs like this.”

dumptrucked more eggs into her being. “Also,” she managed, around the mangled remains of many chicken children, “in real life, I wouldn’t be eating eggs like this.”

“Maybe,” I said.

Al next went to the toast; so did I; mountains of white bread, saturated with butter, all the way through: restaurant divine: good, it was, that yesterday, Al and I, we had hewed strictly to the lean jerky beef, so that, today, there was sufficient room, there in the aorta, for this fat-bomb finery.

“I didn’t mind that you drove your fist into my shoulder like that guy pounding the golden spike to complete the transcontinental railroad,” I told Al. “What really hurt was when you put the ‘House At Pooh Corner’ earworm in my head. It’s still in there. All night, and now into the day. I am, frankly, in torture.”

“What are you talking about?!” Al geysered toast. “You’re the one who brought it up!”

“No,” I held firm. “I referenced the book, or the movie, or maybe the motel. Hoping there was one. In this town. Remember? You are the one, Al, who went to the song. And that was really cruel. I would never do that to you. Fill your head with an infernal song, an earworm, that would play unsanely, over and over and over again, there in your mind, until you finally lost all control, and tried to unscrew your head from your neckpipe, so you wouldn’t, any longer, have to suffer.

“Though you know,” I added, around another slab of toast, “it is traditional, when one is attacked with an earworm, to earworm back.”

“I don’t believe in that tradition,” Al decreed. “And I believe that if you, here, now, try to adhere to that tradition, you will experience a kneecap disorder.”

But I couldn’t help myself. Softly, I commenced to trill; low, so as not to fell anyone else in the restaurant; take out, only, Al: “’I love/the flower girl/she seemed so sweet and kind/she crept into my mind.’”

Al dropped her implements of perpetual motion. “I will murder you in your sleep,” she said. “Can you go to sleep now? Here? At this table? Because I don’t want to wait.”

“Fair’s fair,” I said airily, spearing some eggs from the Hagrid-sized mound on her plate.

“Not fair at all. I did Kenny Loggins. You went to The Cowsills. That’s like bringing a bazooka to a knife fight.”

“Don’t do it, Al,” I warned. For I saw what was flashing, in swords, in those eyes. “Don’t come back at me. With another earworm. I have plenty, plenty more, mountains more, in reserve.”

“And you don’t think I have?”

“I know you have. But engaging in an earworm armageddon will not further the mission. If we slay each other, here, in an earworm apocalypse, we will never get to the alien. We will die, right here, and I don’t think they even have a graveyard in Needles. They will just throw us out in the sand, and the meth monkeys will dig us up, and gnaw on our skulls. Is that what you want? To have the bones of your noseholes, used as a meth pipe?”

“You are so disgusting,” she said. “I should have run you over a long time ago.”

She considered. Then said: “But I won’t do it. Right now. But know that I will come back. At a time and place of my choosing.”

I shrugged. “And then: right back at you.”

We managed to finish all of the breakfasts without further mayhem. We even cleansed one another of our mutually assured earworms. We did so by combining the atrocities. To wit, we came up with “I Love The Flower Girl In The House At Pooh Corner.” It became giddily, goofily pornographic—yea, verily, even unto bestiality—within three lines. It was so deeply ditzy, we dissolved in laughter. But you won’t. ‘Cause, to the uninitiated, this is a mightily jujued, pretty much fatal, earworm. Yea, verily. Someday, we will launch this earworm, upon all you all, upon all lands. And it will be worse than Ice-Nine. And then, shall you all, fall to your knees. Beg. Weep. Call—pray all gods—for mommy.

“That was a worse belly-bomb than three pizzas,” Al announced, as we groaned from the table. “I think I need now to lie down.

“See how smart I was?” Al pleased with herself. “To rent the room for another day?”

When Al had earlier that morning announced she wanted to go to the Cyclops and obtain benediction to red his roof for another day, I had been seized with The Fear. Had Al lost all of her marbles? Were they all rolling around on the floor? Had I just not, that, Seen? Maybe because of the mushrooms? We had built into our timeline room for calamities, but no such calamity as this: that one or more of us would decide we wanted to, yes, yea verily, actually live, in Needles. Become a Needleodeon. I didn’t know what to do. I mean, Al had all the weapons.

“No, you dolt,” she’d said. “I don’t want to live here. I just don’t want to be shoved out at eleven a.m. Yesterday was fucking nuts. Those endless desert meth monkey miles we covered. Today I want to rest on the oars a bit. Like Odysseus on the slave ship. Or was that Victor Mature? Charlton Heston? Pee Wee Herman? Anyway, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that next is Las Vegas, and that’s only about a hundred miles from here. In the plan, we had always decided to stay there overnight, so we could go to Caesar’s, and watch the statues move. Where we won’t need any drugs. Because Las Vegas, it is, drugs. So we have plenty of time. We don’t need to head off again right away. And anyway, we can’t come into Las Vegas during the day. Las Vegas always has to be approached in the night. In fact, I think that’s a law.”

What did Al know about laws? Al was pretty much the opposite of laws. But I wasn’t going to argue. I wanted to rest too. I just didn’t want to rest in Needles. But Needles, that was where we were. So if we were going to rest, it would have to be here.

But before we made it back to the motel, for the rest, Al decided she wanted instead to veer into the gift shop. It was on the walk; the gift place. We’d ignored it, walking in. But now, Al was all about it.

Once we were in there, I recognized it, and at once. It was the gift shop from Something Wild. Except there was no black man at the counter. Because black men, they are more or less outlawed, in Needles. Actually, humans in general, are increasingly disfavored, in Needles. If any town was ever in the last throes of death, depopulation, it was this one. But that’s a story for another paragraph.

The completely and utterly useless tacky swill in the shop depressed me so badly I was nearly weeping openly for Medicine, when Al called me  over. She was standing before some hats. MAGA hats. I cautiously approached, fearing again that Al’s marbles were clattering to the floor. For why would Al ever care about MAGA hats? Except maybe to shoot them with her rifle? But then she smiled, and turned a hat round, so I could read the lettering. And instead of the usual “Make America Great Again,” it read “Make America Grate Again.”

over. She was standing before some hats. MAGA hats. I cautiously approached, fearing again that Al’s marbles were clattering to the floor. For why would Al ever care about MAGA hats? Except maybe to shoot them with her rifle? But then she smiled, and turned a hat round, so I could read the lettering. And instead of the usual “Make America Great Again,” it read “Make America Grate Again.”

“Don’t you see?” Al in her fervent holy vision aspect, as when she’d oracled the revelation that it was the alien who went into the tube to for the Storm send out the Calling You. “This is perfect. Because that’s just what the guy is doing. He’s making the whole country, and everything in it, grate.”

She plucked two hats from the stand. “We are getting these,” she said. And placed one on my head. But it didn’t fit. Too big.

“Hmm,” she said. “For somebody with such a big head, your head is not very big.”

She kept trying hats, fussing them, until she found one that she decided fit me. She meanwhile had one on her own head. Then she armed us over to a full-length mirror.

And there we were. The thing itself. Mad as were ever any hatters ever. In all this world.

Then, she frowned. In the mirror, I saw. What: I wondered: now.

She turned and looked at me, full on. “What we need to do now,” she said, “is cut your hair.”

“What?” This was not only out of left field. It was out of left galaxy. I tried, desperately, to grasp, for some basis. Then flailed: “Are we in Educating Rita now?”

“Of course not. You never even went to college. So how could you be a college professor? And I am not some scrubber of a Liverpubber, like Rita, or that fuck John Lennon. I am from wealth and refinement.”

“Then is it that this is the Something Wild shop?” I tried again. “Except without the black man? And you want to do some makeover on me, like Lulu did on Charlie, before Lulu became Audrey, again?”

Al shook her head. “Charlie was mostly already made over, by the time he reached the gift shop. And Lulu/Audrey was never in the Something Wild gift shop. That was just Charlie. We were in the car, screaming at Ray.”

“Good god.” My bowels froze. “There’s not going to be a Ray in this story, is there?"

“No,” she said. “Ray is still in prison. As far as I know.”

Great. That’s what Lulu/Audrey thought in Something Wild too. If there was going to be a Ray  in this story: that, for me, would be a dealbreaker. I would be bailing. I mean, I was ready to go up against the US military. But not Ray. Thanatos incarnate.

in this story: that, for me, would be a dealbreaker. I would be bailing. I mean, I was ready to go up against the US military. But not Ray. Thanatos incarnate.

But I anyway knew there was no way, even if there was a Ray, that Al, here, in Needles, could even almost, cut my hair.

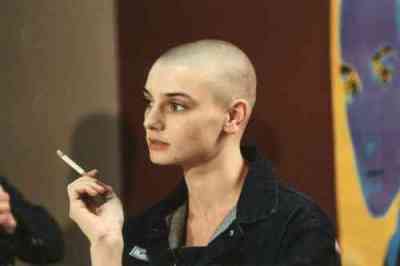

“There are no barber shops in Needles, Al,” I said. “And if there were, the thing would be manned by the Cyclops’ brother, except he would have no eyes, instead of one, and he would just run a razor over every head, on any other body part he stumbles over, in a buzzcut, sending everyone out looking like Sinead O’Connor.”

“No one looks like Sinead O’Connor,” Al said. “She is the only person on earth who has ever looked decent with a shaved head. All the other shaved heads need to be bagged. But we are not going that far, with you. We are just going to cut off enough hair so that we can get in to see the alien. This is for the mission, O. You have way too much hair to ever be allowed past any military outpost so that I can see the alien. They will take one look at the sissified longhair that is you and then laugh and put you in the stockade. And I will then be deprived of the alien. And that is not what will be happening.”

“Long hair doesn’t mean anything any more, Al,” I said. “Look at those nutgong duck people, the Robertsons—they have hair down to their a-holes, and yet they are so stone age even Torquemada says: ‘whoa, wait, slow down some.’”

Al shook her head. “Everything about you weeps soft and soggy and heart-bleeding and I wuv widdle ducks and what about the migrant children? Looking like you do?—the camos will never let us in to see the alien. They will take one look at you, smirk, and go to the rifle butts, and smack you down into the dirt. I will also be doomed, because I am with you. So c’mon. We’re cutting your hair. It’s at least a start.”

And she marched up to the non-black clerk and paid for the Grate hats. She there engaged in some sort of conspiratorial whispering with the man. Who had monkeyed so much meth he was two-dimensional: when he turned to the side, he disappeared. While Al congressed with this occasional apparition, I felt fairly confident. For I knew there could be no one in Needles who could produce a haircut that would get anyone into anything except a jail.

But then Al came over and prodded me to the door, saying, “We’re going back to the motel. I’m cutting your hair.”

“You don’t cut hair!” My brain was at once enfeebled.

“Of course I do. Delilah, that’s one of my names. You didn’t know that? Though you’re not Samson. You’re more like Mr. Rogers. And he would never get past the camos, to get me in to see the alien.”

“I can be Samson!” I protested, as we walked along the early morning sidewalks of Needles, in smothering stifling fetid heated air already approaching temperatures more at home on Venus. “Or at least the jawbone of his ass!”

“You jawbone like an ass, that is a for sure thing,” she said.

“Why are you not complaining that we will drop dead from this heat?” I demanded. “Yesterday you wouldn’t even roll down the windows in the car! Today you’re blithely striding through this Hell like one of those creatures that lives in volcanoes!”

“I am powered by breakfast,” she said. “Now get in the room. Before it wears off.”

When we got to the room Al came out of the bathroom with scissors.

“You brought hair-cutting scissors?” I said, stunned, like the steer who gets that metal rod plunged through his skull, as last rites in the slaughterhouse.

“Of course not,” she said. “These are just regular scissors. But we’re not going to put you in Better Homes And Haircuts. We just need to get you by the camos, so I can see the alien.”

Then she sat me down in a chair, and began the hair massacree beguine. I, pretty much unresisting. It was clear: Al was no longer sane. And: neither was I.

I mean, I’ve been in some wild worlds in my life. But never had I sat in a room of the Cyclops as a woman in a MAGA hat went Sinead O’Connor on my head so that I would be dressed for success  to see the alien.

to see the alien.

I had no idea what sort of hellscape she was up there brimstoning. There was no mirror for me. Just huge chunks of hair, falling to the floor. It was unnerving. As with any haircut. And, as with any haircut, I just had to sit there. And take it. But I’d never had a haircut quite like this one. Never been unnerved, in a haircut, quite as I was, in this one. And so I went to the unnervement. The root of it. This day’s. Before Al ever came into my hair.

“Let’s talk about the dreams,” I said.

“Let’s not,” Al cut.

“Last night I had your dreams,” I said. “I’ve never had a fire dream before. That was one thing I was spared, after the fire. But last night I had your dreams. Where you’re in the fire, and you can’t get out. Last night I was in a place, like a dungeon, with two other men, maybe three, and one whole wall was really on fire, and we threw a blanket up against it, to try to smother the fire, and the fire burst huge, really big and bad, knocked us on our asses, but then suddenly it died stone dead. When we got up, we couldn’t figure out how none of us had burned. In all that fire. Even the blanket had barely scorched. Then we saw this little goat. In the dream I knew this goat had been around me, for some time before, but I hadn’t really paid much attention to it. I’d ignored it. And, in ignoring it, I had deliberately-crueltyed. The sin of all sins. Violated the Blanche commandment. And now, that goat, for us, had taken all of the fire. It staggered around, and we thought it was maybe okay, but then it fell, and its front feet were bloody pulps. You know. Like the feet of the cats. Who’d been in the fire. Sides all scarred; I don’t want to tell the rest. I wanted to stay and help the goat, but the other men shoved me out of the room, said we had to get on with the mission. I was weeping. They passed me on to this other place, where there was this woman. She was some kind of queen. She said I had more to do. For the mission. I said I couldn’t. I said the goat had to be attended to. The goat had to live. She said it wasn’t even a goat, it was a sheep. I said I didn’t care what it was. I said it was hurt, hurt bad, and it had taken the fire, and it needed to be saved. It couldn’t suffer. It couldn’t hurt. It couldn’t hurt. It couldn’t hurt. It just couldn’t. She said there were three women, and each could heal the goat. Who was maybe a sheep. But only one of them could heal this one. And I knew which one it was. I just had to concentrate, so as to pick the right one. And then I did that. I wanted to stay and watch the goat be healed, but then the goddam phone rang, and you wouldn’t answer it.”

“Why would I answer it?” Al scissored. “It was your phone.”

“No, it was the fucking motel phone. You didn’t answer it, and so I had to come out of your dream, before it was finished, and answer the damn thing. And so now I don’t know. Never, do I know.”

“’Never, do I know,’” she mocked. “You sound like some wailing Hebrew Catskills comic. O, I never have any goats, or goats who are maybe sheep, in my fire dreams. That was something about you. But some of the rest sounds familiar. The wall. The blanket. Etc. But I don’t want to talk about it.

“If we’re going to be in the dreams, what I do want to talk about,” she continued to cut, “is how your brother and your father showed up in my dreams last night. Though I know nothing about them. Except what you’ve told me.”

“Drunks,” I said. “Dead.”

“Yeah,” more hair fell. “They were on me about vodka.”

I said nothing.

“And I was a barmaid. I will never forgive you, O, for getting into my dreams, and making me a barmaid. And why you will burn in Hell eternal, is not only was I a barmaid, I was wearing a peasant blouse.”

“Peasant blouses can be fetching,” I tried.

“How ‘bout if I fetch my rifle from the car, and shoot you in the shinbone?”

“You can’t shoot me and cut my hair at the same time.”

“I can multitask.”

More hair cascaded to the floor.

“You know,” she said, “my father, he was great. Until he wasn’t.” She scissored. Curls fell. “The story of men.”

I was going to say something. But then I didn’t. Because what was there to say? She’d said it all.

“Alright,” she at last announced. “I think that’s it. Let’s go look at you.”

We went to the mirror, boy. And I was pretty shorn. My hair now about the length of hers. Shoulder-so. Actually, shorter than hers. So she now had me by the hair, too.

I didn’t know this person. Yet there he was. Looking back at me. Hi. Guy.

“Fire people probably shouldn’t sleep in the same room,” Al said. “The dreams get confused.” She flicked some hair off my back. “What was the phone about, anyway?”

“The Cyclops,” I said. “Wanting to make sure we checked out on time. Though why he’d want to know that at five a.m., when we don’t need to leave till eleven, I don’t know.”

“He’s a Cyclops,” she said. “Who knows where his time goes?”

“I don’t know why you couldn’t answer it.”

“It’s not my job to answer the phone when the Cyclops calls you. Anyway, I thought it was your phone.”

“It didn’t sound anything like my phone.”

“How would I know what your phone  sounds like? Nobody ever calls you. So I never hear it.”

sounds like? Nobody ever calls you. So I never hear it.”

“They don’t seem to be calling you, either, Al.”

“They call me all the time,” she said. “But I put them all on mute. I scrolled through them this morning and there were so many I fell into deep weakness. If not for the eggs, I would be in the infirmary. Just from the thought of calling them back. What do they even want? Most of them aren’t even burned.”

Al then reached into some woman bathroom bag, and brought forth an electric razor. “Now for the beard,” she said.

“Wait, what?” I was again in the poleaxing: the steer in the slaughterhouse.

“Look at the thing,” she said. “All that white. That means you’re dead, you know. When hair starts coming in white, that means you’re supposed to be in the boneyard. And the hair growing out of the edges of your ears: when I was cutting your hair, I nearly hurled, so many times, encountering that: no one with hair growing out of their ears should walk this earth. That’s just a fact. You are fertilizer. That’s the message from the creator, DNA: you are supposed to be dust. I bet if I reached into your mouth teeth in there would be all loose and wriggly. You’re not even supposed to be here. Every day for you is fucking grace. And I don’t know that you’ve earned it. I do know that if I march you up to the camos with all that dead-ass white beard I will never get in to see the alien. So I’m taking it off. Get rid of this dead-ass ugly dead white shit.”

That was enough. “You know, Al,” I said, “you’ve got a little age on you yourself. Your Persephone years, I’d say they’re some leagues behind you.”

“Yes,” she said, “and if you ever reference my age again, I’ll go menopause on you so beautiful and terrible that when they search the ruins of this room they won’t find even a trace of your DNA. And then I’ll Glinda that too, unto all your munchkins, and their descendants. It will be like you never were.”

I said nothing.

“You’ve still got some blonde-red-brown-whatever-color-that-shit-is, going there,” Al said, as she proceeded to mow my face. “In what I think we can get as something like a droopy Wild Bill Hickok moustache. So that’s what we’re going to aim for. Hold still, dammit!”

I watched in the mirror as my face fell away. I hadn’t been outside the beard in probably thirty years. I had no idea what was under there. I did know the beard had come in the first place because I didn’t like what it covered. Now Al was bringing that back.

“I wanted to do this with a straight razor, it seemed more right that way,” she said, “but I’ve never used one before, and I thought I might spout blood. And I can’t have you going into the camos with bandages all over your face. They’ll decide you’re a meth monkey who scratched up his face thinking it was a refrigerator he was repairing at three o’clock in the morning, and then I’ll never get in to see the alien.”

As the flesh of my face came into view, Al was disapproving. “This is whiter than a dead fish belly,” she said. “This won’t do at all. Before we get to the alien I’m going to need to stake you out in the desert, couple days, ten or twelve hours each day, get some sun on that flesh. Otherwise you’ll just look like somebody who shaved off his beard to get off the wanted poster. We can’t call attention to ourselves. It will cripple the mission.

“Don’t worry,” she soothed. “I’ll cover the rest of you with wet burlap, or something, while you’re staked out. So you won’t completely cook.”

When she’d whittled me down to her sought Wild Bill Hickok, she shook her head. “Nope. Doesn’t work. If we’d left you with the long hair, this would have worked, but the hair is gone now, and there’s no bringing it back. Not for several years.”

Oh how I then wanted to stab and shoot. But the only weapon in reach was in Al’s hand. An electrified buzzsaw. And she had it right on my freaking face.

“So let’s keep going,” she said. “See what we find.”

I watched in the mirror, as she continued to obliterate my visage. At one point it looked like she was going to give me a Hitler moustache. At this I would finally have drawn the line. Gone mobile, wrestled her for the razor. Let the blood flow where it may. And from whom. But, mercifully, for which one of us, or both, might have gone corpse, she stopped, before that.

“There,” she said. “Now you have a sort of Sam Peckinpah moustache. Near as I can get there. So don’t complain. Because you like him, don’t you?”

“No,” I said. “I admire some of  his films. But as a human, he was an animal.”

his films. But as a human, he was an animal.”

“So are you,” she said. “Now you look like Sam Peckinpah made William Holden look in The Wild Bunch, because William Holden in The Wild Bunch was Sam Peckinpah. And you are both of them. All of you: you cry, when the deer is shot. You think I don't know that story? I know that story. I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together see how they run like pigs from a gun see how they fly I’m crying. As John Lennon says. Who I still hate by the way. Kinda like the goat. Who was a sheep. In our dream. But now, after I’ve had this go at you, you don’t look like it. The deer-shot guy. Just like they didn’t. That is the secret.”

There was a thread in that babble. But it was thin. It was also, once I’d slid along its thinness, potentially five-alarm.

“Al,” I asked. “Are you expecting me, like Pike, to go up against guns and two hundred men?

“No,” she replied, brushing various hairs off my shoulders. “You just need to look like you will.” Flicked more off my front. “And feel it.”

“I think you may have shot wide on this one, Al,” I said. “You would have been better off leaving me with the white death beard. Because, in The Wild Bunch, the guy with the white death beard, Freddie Sykes, he lives.”

“But we’re not interested in living, O,” she said. “We’re interested in the alien.”

Great. A suicide mission. I suppose next she’ll paint a big red circle on my forehead. Rising sun. Then teach me some kamikaze songs. To sing when we go out to bonzai for the emperor. Who, apparently, is the alien.

And then she said:

“Now for the hair.”

“What are you talking about?! You already cut my hair!”

“Yes, but it’s blond. We’re getting rid of that. Blond on you is lifeless; has been for decades. I’m taking you to the new black. You like to wear black, right? Then wear it on your head. It’s time. Stop wriggling!”

And then she dyed my hair. Black. Never had my hair been dyed. But then never had I gone into the desert to see the alien with Al. And apparently dyeing was part of that. And what kind of person carries hair dye with them, I wondered, as I lay dyeing, wherever they may go, even into the realm of the meth monkeys? It was beginning to dimly dawn on me. That there was more. To the heaven and earth. Of Al. Than I had dreamt of. In my philosophy.

When I was sufficiently dyed to suit her, she reached next into her Merlin’s magic bag, and pulled forth yet another tube of defilement. “Now: the moustache,” she said.

“Why don’t you just use the hair dye?” I groused. “There’s plenty of that slop left over.”

“Because the dye for the facial hair is different from the dye for the head hair,” she said. “Don’t you know anything?”

“No, Al. I don’t know anything about a mushroom and egg addled madwoman with a bottomless bag of razors and dyes transforming me into the William Holden version of Sam Peckinpah in the room of the Cyclops in the hellhole of Needles because such is necessary in order to see the alien.”

“Then it’s as I suspected,” she said, as she dyed me further. “You. Don’t. Know. Shit.”

When the landing strip between nose and lip was dyed to her satisfaction, Al ordered me into the shower. “Don’t get the water on your head,” she commanded. “Or the moustache. But wash all that other hair off. And be quick about it. Then we’re getting you the clothes.”

“What clothes?” I asked dumbly.

“The clothes that will allow you into the alien. You will never get there, O, in those stupid Hawaiian shirts. We’re getting you pearl shirts. You pretend to be a cowboy, don’t you? So why don’t you wear pearl shirts?”

“Because they stopped carrying them in cotton. And it’s against my religion to wear polyester. And also, I got fat.”

“We can’t do anything about the fat. Though I considered cutting it off you with my knife. But then you’d be laid up in the hospital too long, and we’d miss the alien. Anyway, lots of cowboys have belly fat. And also we’re getting you vests. That will disappear the fat some. Almost like a Harry Potter invisibility cloak.”

“Are you a lunatic?” I exploded.

“No, I’m a woman. I know about clothes. Now get in the shower.”

In the shower, I had Thoughts. But I won’t be relating them here. For they were past the wit of man, to say what they were. I would be but an ass, if I go about, to expound these Thoughts. Methought I was—but there is no man can tell, what methought I was. And methought I had—but man is but a patched fool, if he will offer to say, what methought I had. The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man’s hand is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his heart to report, what my Thoughts were. So those, who want to know, what my Thoughts were? Bugger off.

When I emerged from the hair charnel house of the bathroom, Al was at the door to the room. Ready to take, whatever I now was, into the world. “Now to the barn,” she said.

“Why are we going to a barn?” Al had completely lost it. I knew this with certainty. She was going to take me out to some barn, and there hang me, as some sort of sacrifice, at a frenzied black mass of meth monkeys. They would then make her their queen. She would ride at the head of a fleet of meth monkey dune buggies, every night; together they would rapine all the land, grabbing stray desert unfortunates, so that Al could whip out her barbarous implements, and cut off all of their hairs.

“Not a barn,” she said impatiently. “The Barn. It’s where your new clothes live. The guy at the MAGA-hat shop told me.”

“The guy at the MAGA-hat shop had one tooth and three brain cells, Al. He’d say whatever you want him to say. They don’t have pearl shirts in this town. I mean: get serious. They don’t have pearl shirts here any more than they have the Parthenon. In the clothes, in Needles, they have baggy overalls, with lots of pockets, to hold all the meth pipes. That’s all.”

“Well,” she urged, “let’s go look.”

And then she opened the door, and we were into  the solar flares that are Needles.

the solar flares that are Needles.

“Why are you not dying?” I moaned.